Karst Terrane: What It Is, Why It Is Here, and Why It Is Important to Nachusa Grasslands

Part 2: Why It Is Here

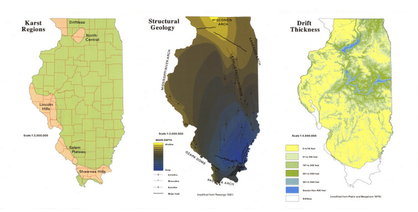

Simply put, there are three requirements for karst terrane to exist anywhere. The bedrock is primarily made up of alternating layers of soluble dolomites and insoluble sandstones. The bedrock is close to the surface, and the overburden is generally sandy, gravelly soil, which allows ground water to penetrate easily to the bedrock. And, the climate is such that there is sufficient water to erode the dolomites.

Of course, there is more to it than that. First the proper layers of bedrock had to have accumulated. For that information, I refer you to a previous blog post by Mark Jordan (“Nachusa's Gift From the Sea,” 9/24/2016).

My purpose is to explain in layman's terms how these sea beds came to be some 800 to 1000 feet above sea level and only inches to no more than 100 feet below the ground surface, as opposed to several hundred to a thousand feet below the surface.

Of course, there is more to it than that. First the proper layers of bedrock had to have accumulated. For that information, I refer you to a previous blog post by Mark Jordan (“Nachusa's Gift From the Sea,” 9/24/2016).

My purpose is to explain in layman's terms how these sea beds came to be some 800 to 1000 feet above sea level and only inches to no more than 100 feet below the ground surface, as opposed to several hundred to a thousand feet below the surface.

Plate Tectonics

Plate Tectonics

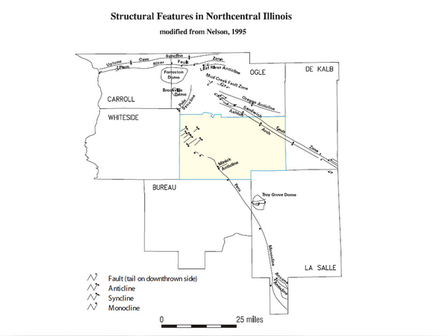

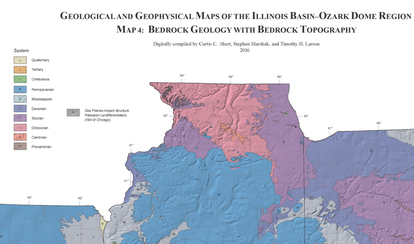

Starting at the bottom, Nachusa Grasslands property is located near the junction of the Mississippi Arch to the west, the Wisconsin Arch to the north, the Kankakee Arch to the east, and the Western Shelf to the south.

Plate tectonics have pushed the Central Illinois Basin up against these arches, or contrary-wise the arches against the basin, and the arches have subducted beneath the local bedrock and kept it near the surface.

Plate tectonics have pushed the Central Illinois Basin up against these arches, or contrary-wise the arches against the basin, and the arches have subducted beneath the local bedrock and kept it near the surface.

Glacial Coverage of Illinois

Glacial Coverage of Illinois

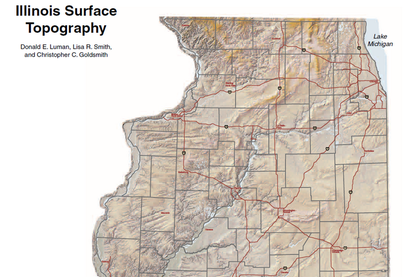

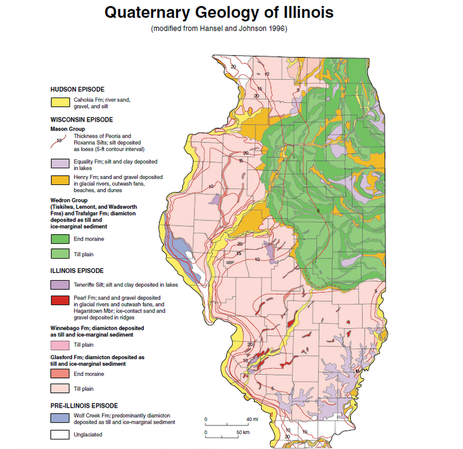

As the land rose above sea level, preglacial rivers shaped the surface of the bedrock. Beginning approximately 2.6 million years ago, this area experienced several ice ages where glaciers advanced into the state then retreated again.

The exact number of glaciations depends on which part of the state you are referring to, but geologists generally divide these into three specific episodes, which are separated by a time span long enough for soil to form and vegetation to grow.

We can ignore the first glacial episode, as the ice cover did not reach northwest Illinois. The second glaciation, known as the Illinois Episode, covered 90% of the state, including this area, effectively wiping the slate clean as far as land formation is concerned. The third glaciation, the Wisconsin Episode, covered northeast and east-central Illinois, pushing rocks and gravel ahead of it.

The exact number of glaciations depends on which part of the state you are referring to, but geologists generally divide these into three specific episodes, which are separated by a time span long enough for soil to form and vegetation to grow.

We can ignore the first glacial episode, as the ice cover did not reach northwest Illinois. The second glaciation, known as the Illinois Episode, covered 90% of the state, including this area, effectively wiping the slate clean as far as land formation is concerned. The third glaciation, the Wisconsin Episode, covered northeast and east-central Illinois, pushing rocks and gravel ahead of it.

All images from the University of Illinois IDEALS Repository

CONNECT WITH US |

|