|

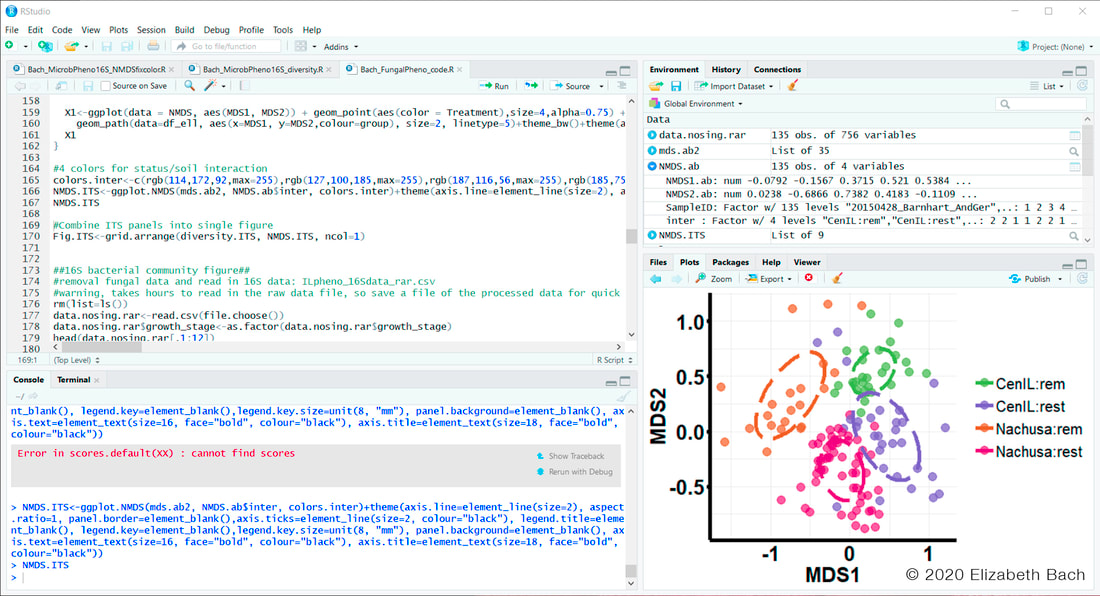

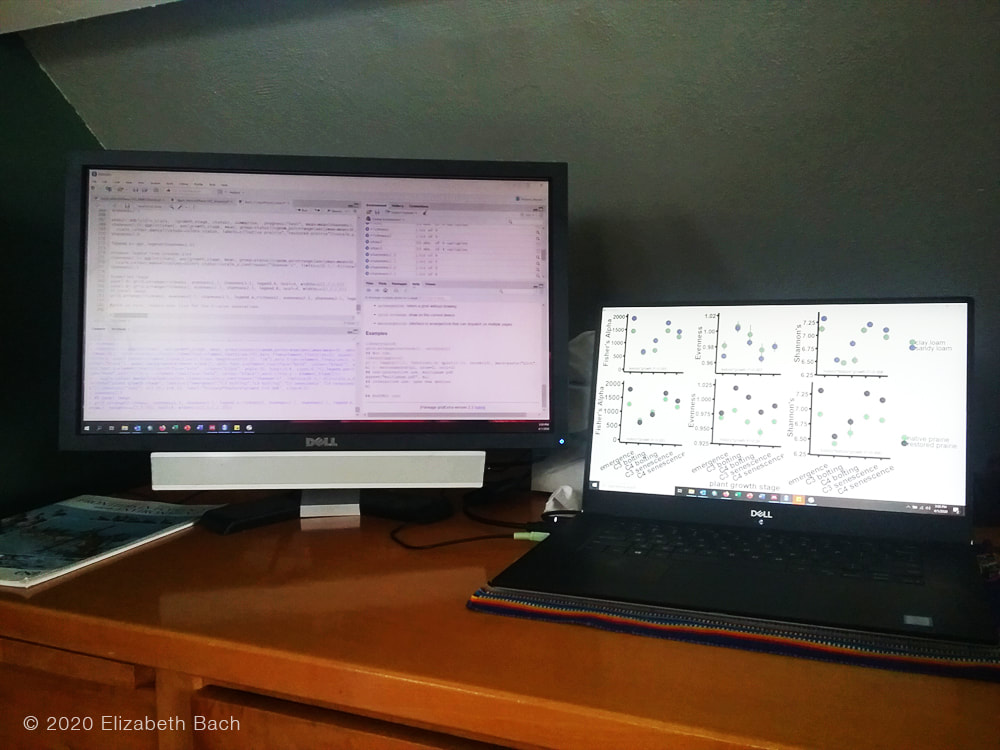

By Elizabeth Bach Ecosystem Restoration Scientist It’s a chilly, rainy spring afternoon, and I sit in front of the computer. Yet I can feel the heat of a sticky August afternoon, hear the whine of cicadas, and see the golden blooms of sunflowers. Mentally, I’m systematically walking through the prairie, carefully identifying all the plants. At Nachusa, many of us, myself included, find working outside in the prairies, savannas, and wetlands most rewarding. However, there is an incredibly important part of conservation work that happens at the computer: data entry and analysis. As the staff scientist at Nachusa, one of my primary duties is to analyze and share data. My primary tool for this work is a free program called “R.” In R, I can manipulate data, produce graphs, run statistical tests, and even produce a final report. Analyzing these data helps everyone at Nachusa refine restoration practices, inspires new ideas, and deepens our knowledge of the habitats and the organisms that live there. Sharing these data in presentations and publications allows us to share lessons learned and best practices used at Nachusa with others in both the conservation and scientific communities. In turn, we also learn from data from other sites. At Nachusa we are lucky to have several scientific researchers working at the site, who collect, analyze, and share data with us. We also have some data, collected over the years by The Nature Conservancy staff and collaborators, which haven’t been analyzed and shared. A key goal for Nachusa is to analyze these legacy datasets and share them. All this brings me back to my computer on an early spring afternoon. When there is less work to be done outside, I’m busy working with datasets on the computer, building graphs, thinking through which metrics best represent the observations made on the prairie, and building statistical models to understand how the Nachusa ecosystem has changed and how it might continue to change into the future. All this work is done with a few lines of code on the computer. While very different from the outdoor joys and challenges of data collection, there are both joys and challenges with this work. I often think of data analysis as a mystery to solve. What will the data show? What will I learn? How might this challenge or confirm observations from other scientists in other places? Every dataset is a new adventure, and I find a sort of excitement in that. It can also be frustrating. I spend a lot of time finding and correcting mistakes. There is no travel guide to inform my decisions. Fortunately, I can work with collaborators as travel buddies on these adventures, to bounce ideas off them, and gain a new perspective. One of the joys of working at Nachusa is being at the intersection of many paths of scientific research and natural history observation. Working with people with different expertise, skills, and perspectives deepens my understanding of science, the tallgrass prairie, and Nachusa. Elizabeth Bach is the Ecosystem Restoration Scientist at Nachusa Grasslands. She works with scientists, land managers, and stewards to holistically investigate questions about tallgrass prairie restoration ecology.

1 Comment

By Mary Meier Nachusa Grasslands volunteer Each May, Nachusa Grasslands’ staff and stewards usually dread the appearance of one of our major weed adversaries, reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea — RCG). This year, however, we may welcome the opportunity to attack the invaders, if and when we are released from our “stay at home” restrictions. The prospect of heading out into the field laden with herbicide backpacks is very appealing right now. What is reed canary grass? RCG is a coarse, cool-season perennial grass with erect hairless stems that grow from 2 to 6 feet tall. Densely clustered single flowers at the top of each plant change from green to purple to tan in late spring. Shiny dark brown seeds form during the summer months and shatter easily. Reproduction takes place both by seed dispersal and underground rhizomatous roots that create a thick, impenetrable mat just under the soil. Seeds can float down waterways and also spread via animals, humans, or machines. For example, Nachusa’s bison and deer populations may brush up against the plants and then carry the seeds in their fur. Where does reed canary grass grow? The plants thrive in moist areas, including marshes, swamps, prairies, meadows, fens, stream banks, and swales. It is especially abundant in disturbed wetlands, but can also appear in high quality native habitat. How did reed canary grass arrive in northern Illinois? Since the 1800s, agronomists have encouraged planting RCG for forage and erosion control. Some states prohibit selling the seeds, but Illinois does not. A native species actually exists, but it is almost impossible to distinguish from the more aggressive Eurasian variety. At Nachusa Grasslands we strive to eradicate all occurrences of RCG in order to diminish its ecological threats. Why does reed canary grass cause problems in our natural areas? RCG forms large monocultures, crowding out native species and building up a tremendous seed bank that germinates year after year. The thick thatch that forms from rhizomes and collapsed stems is especially problematic, as it prevents more desirable seeds from germinating. RCG, therefore, reduces native plant and insect diversity, while providing little shelter or food for wildlife. How do we manage reed canary grass at Nachusa Grasslands? Spraying grass herbicide is our main approach. The staff and stewards treat RCG with Intensity, a post-emergence grass herbicide (1% clethodim). Even though clethodim does not kill the plants’ roots, it helps set back the grasses and allows sedges and forbs to move in. Around waterways and high-quality natural areas, the crew uses the same formula with extra caution to reduce overspraying. What are some other reed canary grass control methods? Research and experience show that burning and mowing can actually stimulate regrowth of RCG but may also be useful in removing thatch prior to overseeding. Digging up rhizomes is labor-intensive and disturbs the soil, so other weeds may then invade the site. In small patches, cutting off the seed heads and disposing them off-site can be effective when combined with herbicide application. Covering with shade cloths is another option for large infestations. As with all weed management projects, best practices depend on overall goals and objectives, the size, distribution, and location of RCG infestations, willingness to use herbicides, and available human and equipment resources. In addition, every method requires follow-up monitoring, treatment, and establishing native species as we strive to extirpate this very challenging invasive species. Mary Meier has been a dedicated volunteer at Nachusa since 2002. She is currently an officer for Friends of Nachusa Grasslands, an Autumn on the Prairie festival organizer, and a member of the social media team. Along with her husband Al, she stewards the Dot and Doug Wade Prairie Unit, which is about half restoration and half remnant.

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed