|

By Josh Klostermann Doctoral Student, Department of Plant Science and Technology at the University of Missouri Have you ever observed a bee tenaciously collect every grain of pollen out of an anther and then zoom off into nothingness? Where did that bee go? An easy answer to that question is back to its nest, but the nesting habits of most bees are mysterious. Where each different species decides to build a nest is poorly understood and not frequently observed. So, it may be more difficult to locate that pollen-loaded buzzer than originally expected. It is at the intersection of this problem and Nachusa Grasslands where my passion for a good hunt, infatuation with natural history observation, and the regionally uncommon bee Anthophora abrupta collide. But first I will give a little backstory. Most bees are solitary, and most bees that are solitary are soil excavators. In other words, a large majority of the bees on this planet live alone (without a hive or queen) and dig underground to build their nests. Where a solitary mother bee chooses to build her nest is arguably one of the most important decisions she will make in her life. There is an immense pressure on her to be able to pick a nesting site that will allow her to operate as efficiently as possible while also reducing the risk of nest failure through predation, parasitism, or infection from pathogens. Once committed to a nesting site she will invest all her energy on that place, visually and chemically remembering where it is, provisioning the cells she creates with hard foraged pollen, and laying eggs on those provisions to ensure that more of her kind will emerge the following year. With these responsibilities, it may be safe to assume that bees must be keen on detecting differences in above and below ground microhabitats in order to choose a site that will allow them to be as fecund as possible in their short lifetimes. Some examples of microhabitat differences that would be relevant to a nest founding bee may be the amount of bare ground at a site, the amount of sunlight the site receives, and the texture and compaction of the soil. The degree to which these differences in microhabitats filter what can exist in a community is largely unknown and an important puzzle piece in understanding how bee species persist. As a researcher, I am focused on how the presence of these microhabitats affect what bees and wasps nest where in a landscape and how disturbances alter the landscape to create many different types of microhabitats for bee and wasp nests. Disturbance is an unavoidable reality in ecology. It is often painted in bad light due to our human ability to disturb so profoundly that it alters communities indefinitely, but not all disturbance is bad. In fact, small scale disturbance at intermediate intervals has been shown to increase the diversity of organisms in an environment and promote co-existence. Therefore, identifying mechanisms of small-scale disturbance that provide this sort of stability to bee and wasp communities is essential to their conservation. One mechanism of disturbance I am becoming increasingly interested in is wind. When a mature tree is downed by wind, several different things happen at a microhabitat scale. First of all, the root system is uplifted and a pit of exposed ground with an associated vertical wall of a soil-root matrix is created. These soils are fundamentally different from the surrounding soil just by the nature of being covered and ensconced in tree roots for decades and then one day suddenly uplifted. Also, canopy cover decreases, and there is an influx of light into the immediate area adjacent to the downed tree. This creates temperature and moisture differences from the surrounding woodland. The disturbance of a freshly-downed tree creates an array of free “real estate” that a bee or wasp may find suitable as a nesting site. This real estate is a hot commodity, and downed mature trees are rare in today’s forests. As time moves on, more trees become downed, and the bees and wasps that utilize these spaces disperse to fresh sites. I believe that this sort of dynamic, small-scale, and intermediate disturbance may be a crucial component to the stability of bee and wasp populations that nest in woodlands. In the summer of 2021, I scoured the wooded areas of Nachusa grasslands and surrounding forests looking for these “tipped-up” microsites. By targeting these places, I have been able to confirm that they are indeed being utilized as nest sites for several different species of bees and wasps. An important discovery was finding Anthophora abrupta at three different sites in Northern Illinois all nesting in the soil-root matrix of “tip-ups”. This bumblebee look-alike is regionally uncommon and was a site record for Nachusa Grasslands. While carefully observing the nesting sites of A. abrupta I was also able to spot their associated cleptoparasite; Brachymelecta californica. A cleptoparasite is an organism that steals resources from another. B. californica will search for nests of A. abrupta, sneak inside, and lay its eggs on the pollen provisions collected by their host. This bee is extremely rare to the region and was a first record for the state of Illinois. Other notable members of the “tip up” community thus far are Myrmosa unicolor, Philanthus gibbosus, Pseudomethoca frigida, and small metallic sweat bees in the Lasioglossum subgenus Dialictus. There is so much more to bees and wasps than flowers and stinging. I hope that this blog post has opened a new window for looking at these small insects with curiosity and wonder. It is through careful observation and patience that insight may be passed from the non-human to the human. The actions of an invertebrate may seem insignificant, but these organisms have been surviving on earth for much longer than us. Next time you’re in the prairie in the sweltering humidity of midsummer and the droning of bees swerving between pink rays and into white corollas feels disorganized, even chaotic, take a swig of water, a bite of lunch, and a closer look: those supersonic meanders may begin to look like slow dances with each bee’s movements holding purpose.

Friends of Nachusa Grasslands awarded Josh Klostermann Scientific Research Grants in 2022 and 2023. Are you interested in supporting research projects at Nachusa? Just designate your Donation to "Scientific Research Grants."

0 Comments

By Luke D. Fannin PhD Candidate, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH Grass-eating, or graminivory, as it is called by scientists, is a strange behavior. At the outset, grasses, at least compared to the many plant foods that humans consume regularly, look unappetizing; they are tough to chew, they are full of fibers that make them difficult to digest, and they are often covered in dust and sand from growing close to the soil surface. But for many mammals, ranging in size from tiny voles (20-24 grams) all the way up to gigantic white rhinoceroses (2400 kilograms), grasses are dietary staples, and these so-called “grazers” (grass-eating mammals) are pivotal in Earth ecosystems. Nachusa Grasslands is home to one of North America’s most important grazing mammals, the bison (Bison bison), which eats grasses in most months of the year. But if grasses are such difficult foods to eat, how do bison–let alone any other mammals–eat them? As it turns out, bison have a few tricks up their proverbial sleeves as it pertains to eating grasses. For starters, bison are ruminant mammals, which means they have highly specialized stomachs that allow them the ability to regurgitate and then re-chew partially digested plant foods. Think of how a domestic cow eats; the cow first swallows a bite of food but then proceeds to regurgitate that bite of food and chew it again, and again, and again… until finally those food particles are small enough to pass through the rest of the digestive system. With each subsequent swallow, foods are bathed in stomach juices teeming with bacteria, which also help to weaken the structural integrity of fibrous foods and liberate nutrients. This digestive trick is incredibly helpful for bison, as it allows them to digest grasses in a way that humans cannot. Secondly, bison are endowed with highly specialized teeth, termed hypsodonty. Unlike the surfaces of our own teeth, which fully poke out of our gums when they erupt, bison’s teeth emerge in a piecemeal fashion over the course of their lives, meaning that they usually have more teeth hiding within their skulls at any given point in time. A good analogy for how bison teeth work is the lead found in the tip of a mechanical pencil: while there is always lead at the pencil tip exposed for writing, there is far more lead stored within the pencil that emerges to eventually replace the used-up lead after writing is finished. Hypsodonty is thus a useful trait for Nachusa bison because most grass plants are also abrasive (see below), meaning they remove tooth surface, or enamel, during chewing. Hypsodonty allows bison to continuously provide new replacement tooth surface over the course of their lives, allowing them to keep eating grass plants without having to worry about completely losing their teeth in the process (although they are not actively growing teeth, and this excess amount of tooth eventually wears out in old age).  Bison teeth are hypsodont, meaning that the dental crowns are tall and most of this length is stored within the bones of the face and jaw. This trait provides a hidden reservoir of tooth material that can be pushed out when the surfaces of the teeth wear, allowing for tooth function to be preserved in the face of extremely abrasive conditions. In addition, when bison teeth wear, the enamel forms elaborate cutting surfaces with a harder underlying tooth material (referred to as dentin, which is the brown material contrasted against the pearly-white enamel on the tooth surfaces). These elaborate cutting surfaces help bison mince plant foods. But with all this talk of bison traits to eating grass, it is easy to view the grasses themselves as passive players in this story of herbivory at Nachusa. But can grasses fight back? My own work at Nachusa Grasslands seeks to answer this question with one plant trait that may act as a defense against herbivory . . . silica levels. While we often think of silica as being a component of our modern technology (e.g., in computer chips), silica is also one of the most abundant minerals in Earth’s soils. Grasses, in turn, uptake silica into their own tissues during growth, where it usually gets deposited into silica bodies called phytoliths. The function of silica accumulation in grasses is debated, but one thought is that it provides a defense against defoliation (i.e., the removal of leaves). As suggested previously, grass plants are abrasive, and it is the silica in grass leaves that hypothetically works to remove enamel. As such, high levels of silica in grass leaves may deter mammalian consumers from eating them — for risk of damaging their teeth — helping to prevent defoliation. Silica also works to stiffen plant leaves, making them more difficult to chew and digest, while also further inhibiting microbial digestion in the digestive tract. Thus, silica be an inducible defense for grasses, wherein a re-growing grass plant responds to previous herbivory by increasing silica uptake to prevent severe defoliation in the future. But silica has other important functions in grass plants that are unrelated to herbivory. For example, increased silica uptake in grasses is also important for relieving environment stresses related to both high temperatures and low water availability. Therefore, it remains challenging to determine whether the high silica levels found in some prairie grass plants are primarily a response to intense herbivory pressure (i.e., from roaming bison) or are instead a plastic response related to changes in local environmental conditions that may increase growing stresses.  Bison at Nachusa can exhibit immense herbivory pressure on the local grassland community and repeat herbivory at certain locations can create what are termed “grazing lawns”, where grass plants are maintained in a short-statured state as compared to surrounding vegetation. It remains unknown whether the grass species within these “grazing lawns” at Nachusa possess higher silica levels in their tissues than similar species within exclusion plots, but previous work on the African Serengeti has suggested that grasses in such features are more silica-rich than similar species under less extreme herbivore pressure. My current work at Nachusa Grasslands seeks to shed light on this mystery. By taking advantage of bison exclusion plots set up across the lands of the reserve, I can compare the silica levels of different grass species (and other related traits, such as photosynthetic pathways, leaf toughness, and nutrient levels) in locations where they have experienced almost a decade of bison herbivory (2014 – 2021) to those same species in exclusion areas where bison herbivory has been much less intense or non-existent. My hope for my continuing work at Nachusa is to disentangle the various factors that may influence silica levels in various grass tissues of prairie plants and, by extension, in the diets of Nachusa bison. My overarching goal is to figure out if re-introduced bison are helping to change the functional traits of grasses growing within the Nachusa reserve, and if so, what this might mean for plant community structure and resilience moving forward.  Exclosure or herbivore exclusion plots are key to testing hypotheses regarding inducible plant defenses and bison herbivory at Nachusa Grasslands. The bison have access to the plants on the left side of the photo, but in the right side of the photo begins the exclosure, a space that is completely isolated by fencing and the bison cannot enter. Notice the taller vegetation in the exclosure. Numerous exclosures are found throughout the bison unit.  The author (L.D. Fannin) in his mobile lab processing collected grass plants in the field at Nachusa in June 2021. To prevent molding, grass plants need to be dehydrated before transport, and the food dehydrator at the far right allows for the dehydration of plant remains to occur quickly before plants are then ground and stored with desiccant. The author is currently analyzing these collected plant parts for their silica content at Dartmouth.

Luke Fannin was a 2021 Scientific Research Grant recipient from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Interested in supporting Nachusa's science? Just designate your Donation to "Scientific Research Grants."

By Elizabeth Bach Research Scientist at Nachusa Grasslands, The Nature Conservancy Nachusa has experienced several ups and downs in 2021. COVID-19 continued to bring challenges and require flexibility. We celebrated the opening of our new equipment barn, but we also grieved the loss of naturalist Wayne Schennum. Wayne conducted plant and insect surveys at Nachusa throughout his long career and was actively working on a survey of leaf beetles prior to his passing this summer. Amid this uncertainty, the Nachusa science community managed to accomplish a lot.

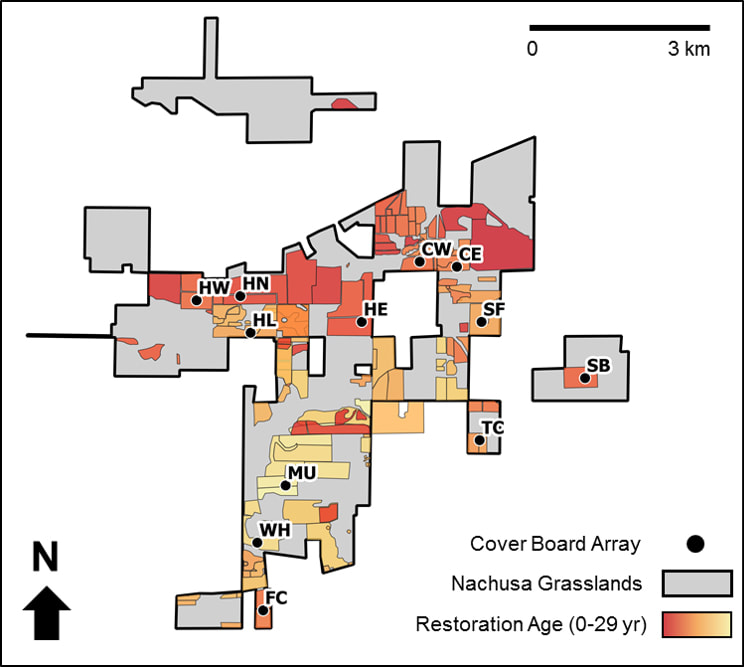

Pete Guiden started 2021 strong with the publication of Effects of management outweigh effects of plant diversity on restored animal communities in tallgrass prairie in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This is one of the top three scientific journals in the world; it is a major accomplishment for Pete and his co-authors in the Holly Jones and Nick Barber labs. It is significant for a Nachusa dataset to contribute to global scientific advancement in this way. They found management-driven responses were more common (and stronger) than plant-driven responses. Restoration age was the main driver of management effects, followed by prescribed fire. Both plant diversity and active management were critical to restoring animal biodiversity. You can learn more from Pete’s blog post. Another significant Nachusa publication was Twenty years of tallgrass prairie restoration in northern Illinois, USA, published in Ecological Solutions and Evidence as part of a global special issue on the UN Decade on Restoration. Elizabeth Bach analyzed 20 years of plant survey data from permanent transects set up by Bill Kleiman. Plant communities on native prairie remnants have maintained or increased plant diversity, including rare plants. Savannas maintained similar levels of plant diversity, but plant communities shifted from understories dominated by brush to herbaceous plants, including native grasses and flowering plants. The special issue on the UN Decade on Restoration also featured a paper from Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar and Sean Griffin. Variation in prescribed fire and bison grazing supports multiple bee nesting groups in tallgrass prairie showed that a mixture of fire and grazing on the landscape encouraged diverse bee communities by promoting bees with different nesting habits. Nachusa bees were primarily ground-nesting (90% of observed species), but stem/hole nesters (3.6%) and large-cavity nesters (6%) are also important parts of the community. This team also published Bee communities in restored prairies are structured by landscape and management, not local floral resources in Basic & Applied Ecology. Large-landscape restorations were positive for bees, as the relationships with floral diversity observed in previous work in small, isolated prairies did not hold up at Nachusa. Several Nachusa insect studies were published in 2021. Michele Rehbein, who surveyed mosquitoes at Nachusa for her PhD work at Western Illinois University, published A new record of Uranotaenia sapphirina and Aedes japonicus in Lee and Ogle Counties, Illinois. Both these mosquitoes are new records for the area and contribute to broader understandings of mosquito communities in Illinois generally. Azeem Rhaman published Disturbance-induced trophic Niche shifts in ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in restored grasslands, summarizing his MS research with Nick Barber at San Diego State University. He found ground beetles consumed a wider range of food sources in areas with bison grazing, particularly with both grazing and fire. Meghan Garfinkel, who earned her PhD from University of Illinois – Chicago, specifically examined insects present in bird diets. Using faecal metabarcoding to examine consumption of crop pests and beneficial arthropods in communities of generalist avian insectivores, published in Ibis, was the first study to leverage next-generation DNA sequencing to analyze diets of entire bird communities. Birds consumed more herbivorous arthropods (plant-eating bugs) compared to carnivorous arthropods (bug-eating bugs). Heather Herakovich published two papers on birds this year. In Impacts of a Recent Bison Reintroduction on Grassland Bird Nests and Potential Mechanisms for These Effects, she found that bison presence did not impact nesting density or vegetation structure, but nest success increased in the first two years after reintroduction. Heather evaluated birdsong to passively survey communities in Assessing the Impacts of Prescribed Fire and Bison Disturbance on Birds Using Bioacustic Recorders. This dataset showed that having a mix of recently-burned, unburned, and grazed habitat in the landscape supported diverse bird communities, as different species have different habitat preferences. It was a strong year for animal publications from Nachusa. Rich King and graduate students Monika Kastle and Callie Golba published two papers about their work on Blanding’s turtle recovery in northern Illinois, including the Nachusa population. Blanding's Turtle Demography and Population Viability focused on modeling needs for Blanding’s turtle populations to sustain themselves. Blanding's Turtle Hatchling Survival and Movements following Natural vs. Artificial Incubation reported on the results from the 2020 release of Blanding’s head-start hatchlings at Nachusa and other sites. Survival rates were variable across the populations, and research continues at Nachusa to find the most effective ways to protect these turtles. Publications of threatened and endangered species extended to plants as well. Katie Wenzell, who earned her PhD from Northwestern/Chicago Botanic Gardens, published Incomplete reproductive isolation and low genetic differentiation despite floral divergence across varying geographic scales in Castilleja in the American Journal of Botany. This work examined the genetic relatedness and floral variability of Castelleja sessiliflora (downy paintbrush) and C. purpurea (prairie paintbrush or purple paintbrush) across their geographic ranges. Both species are evolving, but C. sessiliflora is exhibiting genetic differentiation, whereas C. purpurea is exhibiting differences in flower shape without genetic changes. These are two different mechanisms driving similar evolutionary outcomes. Timothy Bell and colleagues explored population trends in the threatened eastern prairie fringed orchid in Environmental and Management Effects on Demographic Processes in the U.S. Threatened Platanthera leucophaea (Nutt.) Lindl. (Orchidaceae). They found regular burning and wet weather lead to greater blooming populations for the orchid. To evaluate landscape-level plant community and soil characteristics, Ryan Blackburn tested aerial imaging from drones in Monitoring ecological characteristics of a tallgrass prairie using an unmanned aerial vehicle, published in Restoration Ecology. Drone images did an adequate job of evaluating grass cover and mean dead plant cover, but more work is needed to refine this method. Scientific accomplishments at Nachusa are making strong contributions to both scientific understanding and on-the-ground conservation and restoration efforts. Thank you all for being part of this. None of this could happen without the collaboration of scientists, volunteers, donors, The Nature Conservancy, and Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Many of the 2021 researchers were supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. By Becky Jane Davis Nachusa Grasslands Butterfly Monitor For several years, I’ve been trying to start butterfly monitoring with the Illinois Butterfly Monitoring Network (IBMN). Everything finally came together this year. Recently I did my first butterfly monitoring at Nachusa Grasslands. Butterfly monitoring consists of counting butterflies by species, in a specific route, throughout the season. This first year, I need to identify only 25 species of butterflies. Forty years ago, I could identify more than that, but I'm a bit rusty. So, I walk at a regular pace, scanning the area, left and right on the trail, spotting butterflies. As I see one, I identify it and mark it on my field report. When I’m finished, I enter my findings in the database. It sounds easy and straightforward but my first time out, I identified about half. The rest were noted as “unknown butterflies,” so I have some learning and growing ahead of me. Things they don’t teach you in butterfly monitoring training: 1. How do you count each Monarch only once? They go here, over there, cross over the trail, and then you wonder, did I already count you? 2. Prairie plants are dense and tall. Those little butterflies can dart across the trail and into the plants and disappear before I can even see the markings or colors. 3. You need to protect yourself from ticks. That means bundling up head to toe in insect repellent-treated clothing, wearing hiking boots. Take a walking stick for uneven ground, don’t forget binoculars (if you can get them out and focused fast enough). There must be a simpler way! 4. It is good to know what a species looks like both flying and resting, but what about moving so fast, never resting, and not at an angle to fully see all four wings at once, as in the photos? 5. Back when I knew all the different species, it was because I caught them, put them in a kill jar, mounted them, and used a detailed key to identify them. No guessing! When my route is done, I have a short 10-15 minute walk back to the parking lot that allows me time to linger, get out my iPhone for a few photos, or get my good camera out to capture prairie life. I hope to get back to butterfly monitoring at least five more times this summer, hopefully more. Weather is an issue, as is distance, because I chose a location an hour away from my home. I like going to Nachusa, but it is at least a 3 hour commitment to monitor and I need to leave room in my days and flexibility so I can make that trip. Weather has not been helpful this last month. Rain, wind, and cloudiness are not good for butterfly sightings. In fact, I have rules to follow: at least 70 degrees, partly cloudy to full sun, little wind to moderate wind, and no rain. The last two weeks didn’t give many days to choose from. But I will continue and try to get more of my own photography adventures in as well. The native grasslands and prairies offer so many opportunities for interesting captures. I’m looking forward to what I can share in future blogs! Butterfly monitoring data from 7/17/2021: The route was about 50 minutes. Temperature: 77 degrees Wind speed: 9 mph. The wind was stronger at the end of the route. Sky: partly cloudy

Who are the citizen scientists, and how can I become one? Nachusa’s citizen scientists are composed of community volunteers who are passionate about their subject and want to contribute to scientific research. Do citizen scientists need prior experience or a science degree? No previous experience or scientific background is needed to volunteer, although some monitoring programs require approved initial and/or refresher trainings. Some citizen scientists may desire to seek further training and acquire new skills, while others can assist trained citizen scientists to learn the monitoring process. What citizen scientist opportunities are available at Nachusa?

How can I become a citizen scientist at Nachusa? It’s simple, just sign up on the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website. To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends of Nachusa Grasslands can also be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

By Peter Guiden, PhD Post-Doctoral Fellow, Northern Illinois University An ecosystem is a complex, wonderful thing. It represents many species of plants, animals, and micro-organisms interacting with each other and the air, soil, and water. It is greater than the sum of its parts. And in restoration ecology, a central goal is to put degraded ecosystems back together. However, doing so is often a challenging process—that same complexity that makes an ecosystem beautiful can also make it difficult to manage. A logical starting point is to restore the native plant community. Plants play so many important roles in an ecosystem: they provide habitat and food for animals, they exchange nutrients with microorganisms, help develop soil, and link aboveground and belowground worlds. Every plant species plays a different role in the environment, so land managers often aim to restore as many native plant species as possible, leading to high biodiversity. At Nachusa, prescribed fire and bison reintroduction are used to meet this goal, knocking back the most competitive plant species and allowing many species to coexist. Hopefully, these diverse plant communities support many diverse animal species…right? It turns out that this question isn’t often asked. It’s difficult to answer, because scientists often specialize on one group of organisms, and individually lack the tools to measure how the ecosystem as a whole responds to management. Answering this question requires assembling an Avengers-style team of researchers, who can complement each other’s interests and expertise, at the same place and time. Luckily, the Nachusa community provided an opportunity for this to happen. Through collaboration between Nachusa, Dr. Holly Jones’ Evidence-based Restoration Lab at Northern Illinois University, Dr. Nick Barber’s Community Ecology & Restoration Lab at San Diego State University, and Dr. Rich King’s lab at Northern Illinois University, we could start to look at links between plants and animals. Each of these groups brings a unique skill set to the table. Dr. Jones and her students study plants and small mammals such as wild mice and voles. Dr. Barber and his students study plants, ground beetles, and dung beetles. Dr. King and his students study larger wildlife, such as snakes. Each of these groups has collected data on these animal communities over the past decade at Nachusa, including how many species occur in these study sites, and in what abundance. This gave us an opportunity to combine our data, and ask some broad, general questions about how restoration works. Here’s a link to the study we did, if you’re interested in the technical details. We wanted to know whether the areas with the most plant biodiversity also had the most animal biodiversity, or if something else explained patterns in animal communities. If plant and animal biodiversity were linked, that would suggest that restoring diverse plant communities may lead to recovery across the ecosystem. However, if the link between plant and animal biodiversity isn’t strong, other management strategies may be needed to boost native animal species. We found that in general, the best explanation of animal biodiversity had little to do with plant biodiversity. For example, small mammal communities were most diverse in areas that hadn’t been burned for a few years, because species like voles make their habitat in thatch (dead plant litter). Similarly, snake communities were most diverse in older restorations, because certain species take a relatively long time to colonize new habitats. This isn’t to say that plant biodiversity is unimportant for animals: there were many cases where plant and animal biodiversity were linked. Small mammal communities were more diverse in habitats with a rich mixture of forbs and grasses, and the most diverse ground beetle communities were found in areas with many plant species. But on average, the effects of management on animal biodiversity were six times stronger than the effects of plant biodiversity. Why didn’t we find a strong link between plant and animal biodiversity at Nachusa? One potential explanation is our choice of study species. Snakes and beetles are carnivorous, while small mammals are opportunistic omnivores, eating both plants and animals. Perhaps animals that are strict herbivores (especially insects with very particular diets) would have been more responsive to plant diversity. But for our animals, the age or structure of the plant community seemed to be more important than the number of plant species present. It’s also important to point out that maximizing animal biodiversity may not be the most important goal in a restoration project. Protecting rare species (like the rusty patch bumblebee) or species that play an especially important role in the ecosystem (like large dung beetles that eliminate large volumes of bison dung) may take center stage. In cases where restoring animal biodiversity is important, however, it may be necessary to consider how land management affects both plants and animals. One key take-home message of this study is that restoration really works. Through the hard work of land managers, volunteers, and scientists, it is possible to recreate diverse plant and animal communities in a very agricultural landscape. While we are constantly trying to learn more about how exactly these species respond to restoration, it is important to reflect on these successes. Ecosystems continue to be mysterious in many ways, but understanding a little bit more about them may help preserve their majesty and diversity for the future. Pete Guiden's ongoing research on restoration ecology is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

By Elizabeth Bach Ecosystem Restoration Scientist With 2020 drawing to a close, Nachusa science has several accomplishments to recognize:

Science PublicationsScientific publications are the product of years of hard work, collecting and analyzing data as well as writing the paper. I’d like to use this blog post to highlight some of this recently published research. It has been an exciting year for Dr. Holly Jones, Dr. Nick Barber, and their lab groups. Holly and Nick began research at Nachusa Grasslands in 2013 as new faculty at Northern Illinois University (Nick is now at San Diego State University). Their work investigates restoration outcomes related to planting age, prescribed fire, and grazing. In 2020, the team has published five papers:

The Wildlife Epidemiology Lab, led by Dr. Matt Allender, at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has included Nachusa Grasslands as one of their sites in on-going health evaluations of wild turtle populations. Research scientist Dr. Laura Adamovicz has published three papers from her PhD dissertation:

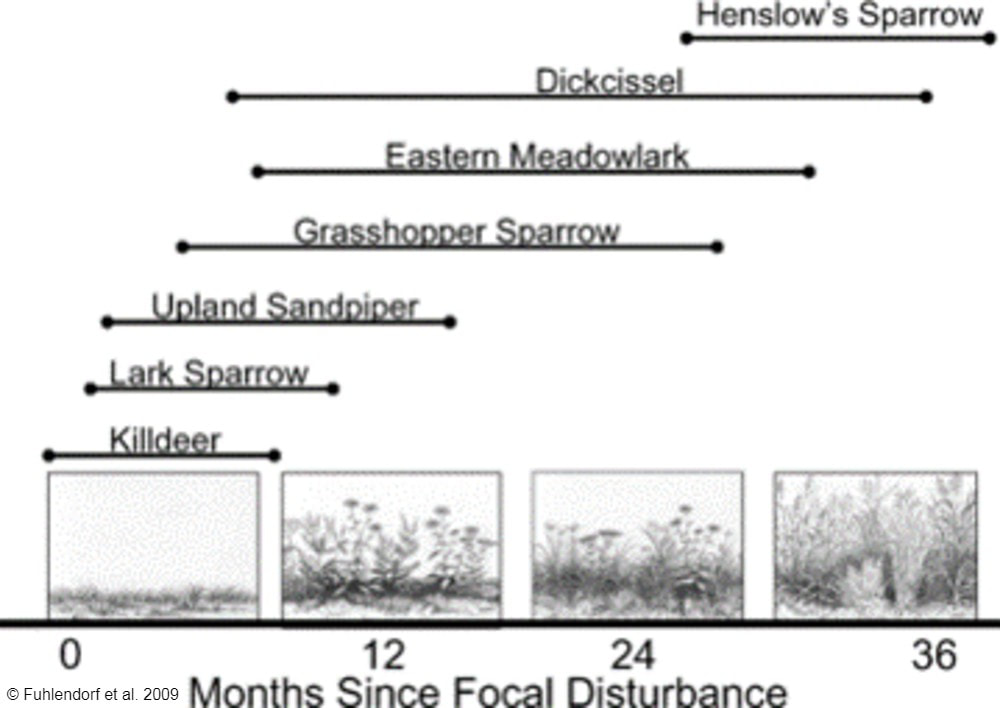

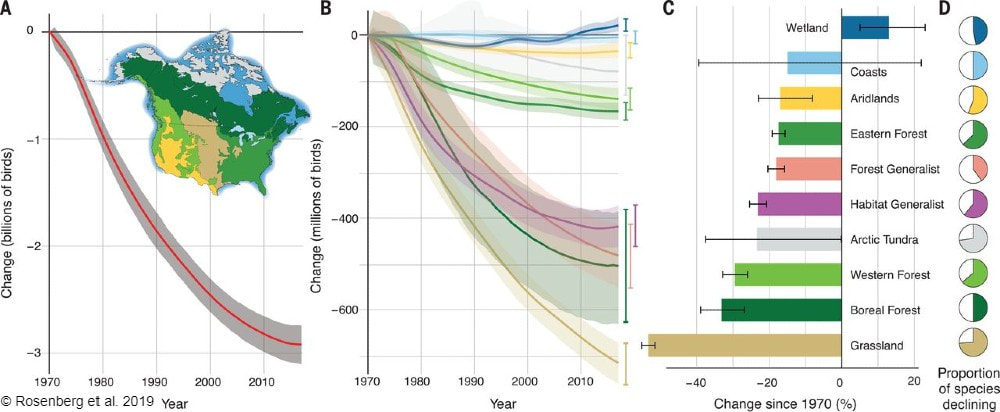

Devin Edmonds, who is a graduate student with Dr. Michael Dreslik at UI-UC and the Illinois Natural History Survey, examined Reproductive output of ornate box turtles (Terrapene ornate) in Illinois, USA. This is the first assessment of ornate box turtle reproduction in Illinois. Meghan Garfinkel earned her PhD from University of Illinois-Chicago this spring. Her research quantified crop pest suppression by songbirds. She found Birds suppress pests in corn but release them in soybean crops within a mixed prairie/agriculture system. Additional data is needed to see if these results can be applied more broadly on the landscape and across years. These initial results indicate birds could provide sizable services to agricultural land around prairie habitat. Physlis Pischl, a PhD student at Northern Illinois University, performed an elegant analysis of Plastome phylogenomics and phylogenetic diversity of endangered and threatened grassland species (Poaceae) in a North American tallgrass prairie. The work showed endangered and threatened grass species were more closely related than expected and likely evolved together in specific grassland habitats. Destruction of those habitats have resulted in many closely related species all being endangered and threatened. Read more about this study. John Vanek shared his work with Dr. Rich King surveying snake communities at Nachusa in this recent blog. John also published Observations of American Badgers, Taxidea taxus (Schreber, 1777) (Mammalia, Carnivora), in a restored tallgrass prairie in Illinois, USA, with a new county record of successful reproduction. While it is no surprise to find badgers at Nachusa, this is a new confirmed report of breeding badgers. Hana Thixton found Further evidence of Ceratobasidium serving as the ubiquitous fungal associate of Platanthera leucophaea (Orchidaceae) in the North American tallgrass prairie (open access) in her MSc research with Dr. Betsy Esselman at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Ceratobasidium fungi were by far the dominant fungal partner for EPFO, and genetic diversity of those strains was limited, indicating the fungal partners were consistent across sites. Drew Scott found Plant diversity decreases potential nitrous oxide emissions from restored agricultural soil in this research as part of his PhD dissertation at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. In this study, he found nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change, from soils at Nachusa with high plant diversity were about seven times lower than from areas with low plant diversity. View the complete list of Nachusa publications. By Antonio Del Valle MS Student  Sunrises over the tallgrass praire were a wondrous daily event to behold while surveying at Nachusa Grasslands. This summer, as part of my graduate research project at Northern Illinois University, I had the opportunity of studying some of the many bird species that call Nachusa Grasslands home. Luckily, surveying birds is an activity that you can do by yourself, which was a key factor in being able to safely conduct my research project in the midst of a global pandemic. The focus of my research is to determine how birds that breed on the prairie are impacted by some of the large scale disturbances on the prairie landscape—mainly bison herbivory and prescribed fire. Different bird species prefer different types of prairie. Species such as killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and upland sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) prefer shorter prairies that, at Nachusa, are maintained through the eating of plants by bison and frequent prescribed fires. In contrast, species such as Henslow’s sparrow (Centronyx henslowii) and sedge wren (Cistothorus platensis) prefer dense, tall prairies that are maintained through infrequent disturbances.  A figure describing the relationship between different grassland bird species presence and months since a disturbance event has occurred on the prairie. Grassland birds are a suite of species that specialize in using prairie habitat as their preferred place to breed and raise young. These species are of particular interest to me because grassland birds have experienced drastic population declines. A recent paper published in Science shows just how serious this decline has been.  Bird populations in North America have declined by three billion individuals since 1970. Grassland birds in particular have declined more than any other group of birds. But it is not all doom and gloom for these grassland birds. Thanks to the hard work put into the restoration, management, and conservation of the tallgrass prairie habitat at Nachusa Grasslands, there are bountiful places for these types of birds to breed during the summer. My research aims to help us understand more about these declining species. Preserves such as Nachusa Grasslands give me an opportunity to observe them in areas where they are still relatively prevalent.  High quality prairie restorations take a lot of hard work but provide great habitat for many declining and rare plants and animals. A typical morning of surveying birds starts out by waking up well before sunrise. I set my schedule to arrive to Nachusa around 5:30 AM in order to start surveying during peak bird activity. Coming prepared with coffee and waterproof clothes were key factors in staying awake and dry while traversing the dew-soaked prairie. Upon arriving to a survey point at the preserve, I begin surveying birds via sight with my binoculars, as well as by sound. I record all of the birds I see and hear into my field notepad for five minutes. While surveying, I record the number of individuals of each species, estimate their distance from me, and record any breeding behaviors that are displayed. Surveying in this systematic fashion allows me to look at the data later and compare what birds were seen in what areas, how many were present, and whether I can confirm that they were breeding (according to eBird’s breeding bird behavior codes). Additionally, this format allows me to compare my data to other data sets across different years and potentially different preserves/sites.  The depth of the thatch layer covering the ground is measured by using a ruler. This layer of dead plant material is important for certain species that require cover. In addition to surveying birds, I also survey vegetation and bison density through dung counts. Vegetation surveys involve measuring vegetation height, thickness of thatch layer, and percent cover of plant species. These measurements give me quantitative values to describe the vegetation structure within different areas of the preserve. Bison density is calculated through systematically counting units of dung at my survey locations. Looking at bison density in different areas of the preserve can help show where bison are spending most of their time (and eating more plants). One of my favorite birds to observe this summer was the Henslow’s sparrow. This secretive sparrow is rarely seen on the prairie, as it spends most of its summer down low in the grasses and only pops up once in a while when singing or flying. The Henslow’s sparrow song is unique as well. Cornell University’s All About Birds online field guide describes it as the simplest and shortest song of any North American bird, and to me it sounds like a faint hiccup. These sparrows have a greenish wash on their face and fine streaks on their flanks, which help to distinguish them visually from other sparrow species if you have the pleasure of catching a glimpse of them. They, along with many of the other grassland breeding birds, are now on their way back to their overwintering grounds in Central and South America. The prairies will be noticeably quieter until they begin to return in the spring again. I’m looking forward to analyzing the data collected this summer and preparing for next year’s field season over the next few months. I hope that my research can help provide knowledge to aid in the continued conservation of these grassland bird species. Nachusa Grasslands is a wonderful place to observe these birds and many other plants and animals in their native habitat. Citations & Resources: Fuhlendorf, S.D., et al. (2009). Pyric herbivory: Rewilding landscapes through the recoupling of fire and grazing. Conservation Biology 23:588–598. Rosenberg, K.V., et al. (2019). Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 366(6461):120-124. Tony’s ongoing graduate research is supported by the following sources:

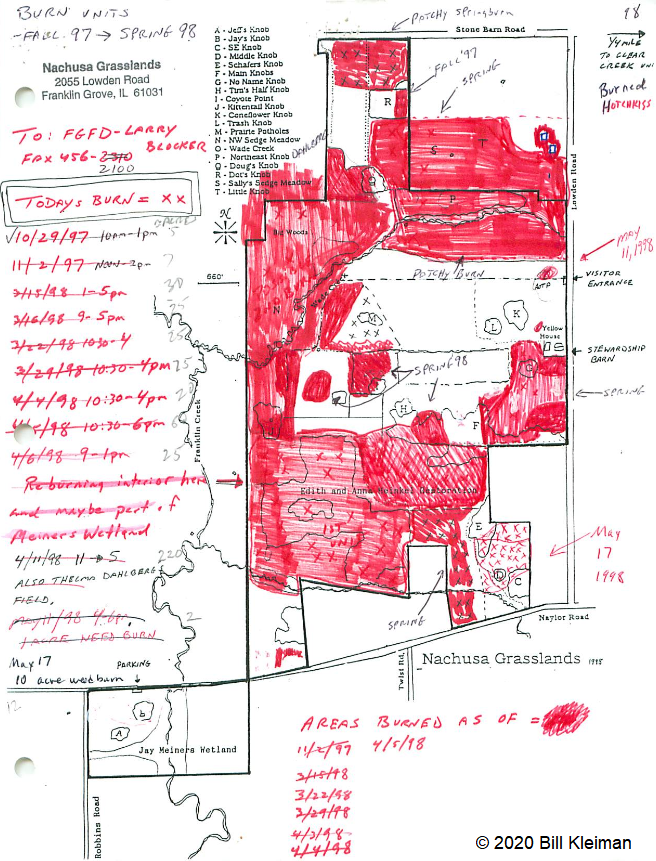

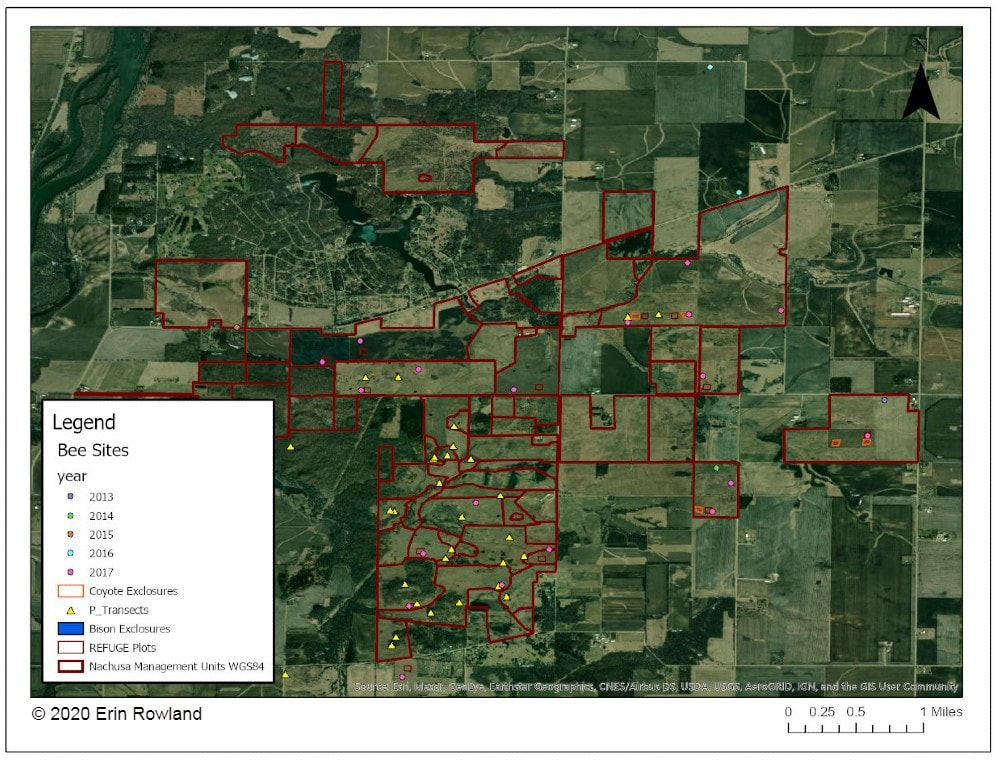

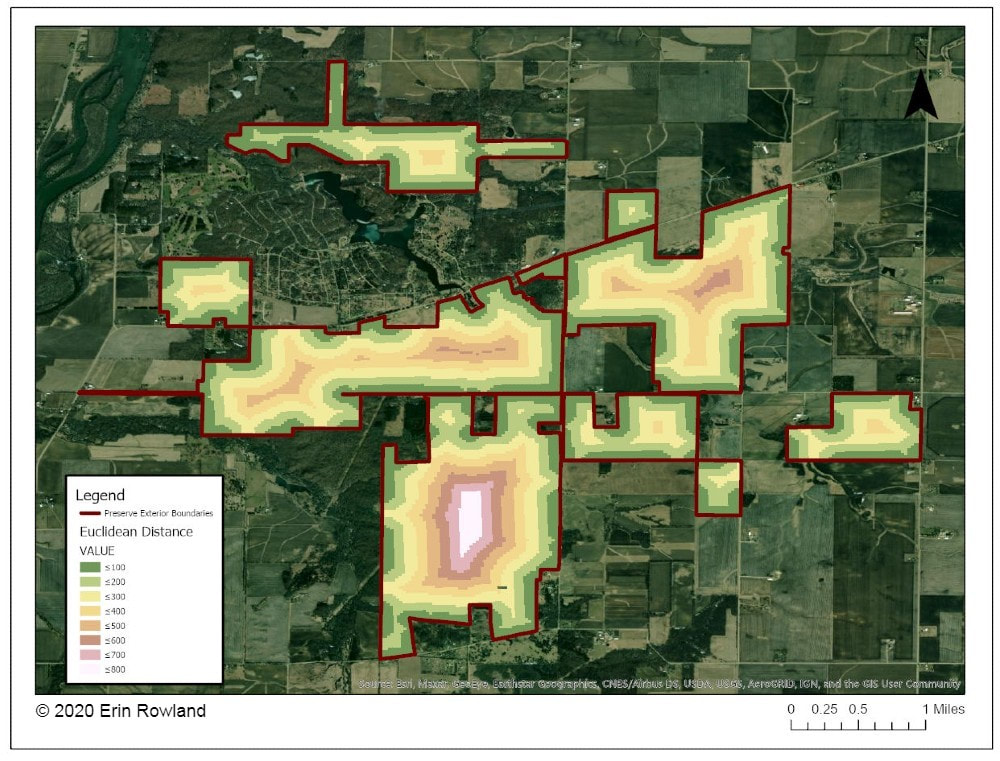

By Erin Rowland Summer Science Extern  Picturesque restorations like this are made possible by the work of volunteers and stewards on the ground. Science provides a new lens to better understand the impacts of this work. When I think of prairie restoration, I tend to think of the hands-on. I picture crews of volunteers collecting buckets of seed, or the summer crew fanned out in a line spraying weeds. Even the science done at Nachusa tends to conjure images of researchers trekking through the tallgrass after Blanding’s turtles, rodents, or butterflies. When I pictured my summer as Nachusa’s summer science extern, these were the images that filled my head. I couldn’t wait to spend my weeks under the sun trapping small mammals and surveying plant diversity. Meanwhile, the universe had other plans. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, research looked a little different this year. Many field scientists were able to conduct safe and socially distant work, while some researchers had to cancel their field seasons altogether. I was one of the unlucky ones. Instead of a summer in the field, I spent the summer at a computer. The funny thing is, this turn of events helped me to see the big picture. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a broad category of science that combines geography with other disciplines to create smart maps and analyze data throughout space and time. It’s a booming field, and it touches every aspect of our lives, whether we see it or not. GIS is used in everything from urban planning to public health to ecology. It allows us to ask and answer really interesting questions such as how the arrangement of land patches and proximity to different types of cover impact everything else on the preserve. This summer, I spent my time looking at the preserve from above in aerial imagery, trying to understand how all the pieces fit together. I spent a lot of my time converting old images of prescribed burn locations into a digital format, a process that feels a lot like a small child playing connect-the-dots. Tedious as it may be, this labor of love will help us see patterns through time in a new way. We can now easily ask how frequently certain areas of the preserve are burned and what that might mean for the plants and animals who live there.  Historically, records of prescribed burns were hand-drawn and not very precise. Our new digital fire maps are uniform and standardized, which will improve our ability to use the information. The second aspect of my work this summer was a bit more practical. Collaboration is one of the most valuable components of research at Nachusa Grasslands, and it’s part of what makes me so excited about working there. There’s such great diversity in the projects at Nachusa, as you can clearly see from the spectrum of projects funded by the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands science grants. One of my goals this summer was to compile a map of all the long-term research sites on the preserve, as well as to describe the types of data collected on these plots. By making information about data more broadly accessible, we can support better science that can benefit Nachusa and other prairie restoration sites. Researchers are better able to collaborate if they know what data exists and to whom to talk about it.  A map of long-term research sites at Nachusa will help researchers to more effectively collaborate and establish new projects more easily. The third part of my work this summer was beginning to understand the impact of human-made boundaries on a natural system. Plants and animals don’t care at all about the arbitrary places we draw our lines on a landscape. A piece of habitat is all the same to them, regardless of who owns it. This means that we have to be aware of the places where we create borders and boundaries and understand the impacts that they may have. A simple mowed path for a stewardship vehicle may seem minor to us, but might represent an insurmountable obstacle to a vole. One of the most exciting revelations of my work this summer is a success story in the tallgrass. I conducted analysis to understand how insulated different areas of the preserve are from the surrounding landscape. I created a heatmap to illustrate distance from the edge of the preserve, an attempt to classify land by how far it is from the proverbial “edge.” The results showed that the best-insulated area of the preserve is part of the original purchase that established Nachusa Grasslands. Not only was a beautiful portion of remnant prairie preserved, but the land around it was converted to create a pure prairie landscape with a buffer of protection from the surrounding agriculture and development.  This map helps us to understand how close various areas of the preserve are to non-prairie edge. We can see which areas are the most insulated from external impacts. Management happens at a variety of scales. Many decisions are made at the smallest scale: an invasive species can be removed from a part of a unit, and seeds can be collected from a rich patch of big bluestem to be planted next year. What’s harder to consider is how these seemingly small decisions work in tandem to create larger-scale impacts. The preserve looks different from above than it does on the ground. The challenge for managers is to be able to simultaneously see the prairie and the plants, as well as the forest and the trees. To meet the needs of a prairie restoration, one has to imagine the view of a turtle or a ground squirrel, in order to imagine a patch of grass as your whole world. At the same time, one must consider the big picture. Making decisions on the small-scale for the sake of specific animals or desirable plants can negatively impact the overall health of a system. What excites me the most as a researcher at Nachusa is the opportunity to do science that helps us make better decisions in restoration. By taking a step back out of the grass this summer, I had the chance to look at the preserve from a different perspective. I gained a new appreciation for the complexity of a prairie restoration project and the multi-faceted decision-making with which land managers are tasked. Now I look forward to taking my maps and figures and using them to ask more questions about how our work changes the landscape and how the landscape changes our work. Erin Rowland's ongoing research on small mammals and landscape ecology is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. To get involved withe the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. If you are interested in learning more about Erin's small mammal work, check out the recent blog by Jessica Fliginger or contact Erin to learn about opportunities to volunteer!

By Chandler Dolan Bumble Bee Technician Introduction The scene: It’s a classically humid, July afternoon. A gaze across the prairie shows patches of yellows and pinks, suggesting the presence of yellow coneflower and wild bergamot. As the heat intensifies, the birds and bison seem to slow. You stand quietly, intently listening to the sounds the grassland offers. Suddenly, a loud buzz tears through the patterns of bird melodies and katydid song. A familiar yellow and black face emerges from under a canopy of partridge pea: a bumble bee. Bumble bees are familiar insects. The shaggy combination of yellow and black (and sometimes orange) hairs with a plump, round build makes these insects nearly unmistakable. Their role of pollinating beautiful wildflowers and food plants alike is an important ecosystem service they provide us, free of charge. Their friendly buzz and frantic foraging suggest a healthy ecological system. Unfortunately, bumble bees face an uncertain future. Through habitat loss, pesticide use, and disease, many bumble species have experienced significant decline and are becoming increasingly rare. Thankfully, Nachusa gives refuge to three threatened species of bumble bees, including the critically endangered rusty-patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis). In 2017, Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar discovered the presence of the rare bumble bee at Nachusa in the form of a foraging worker. This was a great discovery, as the current distribution of the species is fairly unknown. To know this species was living at Nachusa was special and has given rise to new research opportunities and questions to be answered. With the new motivation of a federally endangered species in the Grasslands, new projects have begun! The 2020 season is the first season we have boots on the ground (in the form of me!) to monitor bumble bee abundance and diversity across all species of bumble bee at Nachusa. We start with simple questions: What species of bumble bees are here? How many of them are there? What flowers are they using? By answering these questions, we can start to form new questions and learn about the Grasslands. This season is all about exploration, experimentation, and just getting a sense of the bumble bees at Nachusa. Endangered Bumble Bees of Nachusa Grasslands As mentioned, the rusty-patched bumble bee is a federally recognized endangered species in the United States. In fact, it is the first bumble bee species to be listed on the United States Endangered Species Act. This characteristic bumble bee sports a unique “rusty patch” on its abdomen, which is one of its best identification traits, hence the name. The decline of this species is somewhat mysterious and very sudden. Prior to 1996, this species was abundant throughout much of the Midwest and Northeastern U.S. After 1996, the species tumbled into rapid decline and is now extremely rare in the Northeast. Most records of this species today are sporadically reported in the Midwest, but at very low rates. In the seven weeks I have been surveying, I have detected two rusty-patched bumble bee workers at Nachusa. To know this species is still present and not extinct is a great discovery alone. But understanding the way it uses the mosaic and where it chooses to nest is still up for question, and is difficult to answer with such sparse sightings. Our first sighting occurred very early in the field season. In fact, it was the fourth day of surveying! Seeing a single rusty-patched worker busily foraging on beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis) was a great way to start the season. Our second was about a month later on July 17th. Upon my arrival to a hill to do some quick exploration, the very first bee I spotted was the rare but distinct bumble bee methodically feeding on wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa). I held back tears of joy as I quickly netted the bee for proper identification. Nachusa also houses two other declining bumble bee species: the golden yellow bumble bee (Bombus fervidus) and the American bumble bee (Bombus pensylvanicus). Bombus fervidus has quickly become one of my favorite species, as its striking yellow abdomen and bold, black thorax band are impossible to miss. While these species are not recognized as endangered by the federal government, they have documented declines that warrant them a “vulnerable to extinction” assessment by the IUCN Redlist. I’m happy to report that these species are detected regularly and seem to like certain parts of the Grasslands. One day we hope to answer these questions: What parts of Nachusa are these vulnerable species found, and why? What makes one patch of habitat more suitable than another? Conclusion Bumble bees are interesting. Their familiarity provides a calming energy, as their small wings effortlessly lift their seemingly oversized bodies and loads of pollen to provide for the nest and its offspring. But despite how recognizable they may be, there is still much to learn about them. Simple things such as their habitat and favorite flowers are yet to be fully understood. A closer look into the world of bumble bees reveals a world of individual decision-making by our hairy friends that we are working hard to better understand. One of the first steps to conserving a species is to better our understanding of them. With the first long-term bumble bee surveying season at Nachusa underway, we hope to better understand our bumble bees and to one day provide them the best habitat we can. To lose a species is to lose a piece of a puzzle. Once gone, the picture will never be the same, with a hole no other piece can fill. *** UPDATE: On July 29th and 30th, two more rusty-patched bumble bees were observed at Nachusa! That makes a total of 4 observations this season! *** Dr. Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar's ongoing research on Nachusa's bumble bees is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. If you would like to play a part in helping the bees at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. Chandler Dolan graduated from the University of Northern Iowa in December of 2019. Throughout Chandler's career as a young biologist, they have been continually drawn to endangered species ranging from the rusty-patched bumble bee to neotropical parrots and migratory songbirds. As Chandler dives deeper into the world of bumble bees, they hope to pursue bumble bee conservation as a long-term goal for graduate school.

By John Vanek, PhD Associate Wildlife Biologist® As scientists, we know a lot about snakes. We know that snakes evolved from lizards. We know that snakes don’t have eyelids or external ears. We know they can eat things bigger than their own head. Some species, like the black-tailed rattlesnake, are good mothers, stick around after birth, and protect their offspring. Recently, it was discovered the snakes can even have friends! Suffice it to say, snakes are awesome. So awesome, in fact, that some of us prefer them to grasshopper sparrows and fringed gentians (don’t hit me!). Yes, we herpetologists (scientists that study reptiles and amphibians) are a weird bunch, with our metal probes and pillowcases . . . anyway, I digress. While we know a lot about snakes and how cool they are, we still have a lot to learn, particularly when it comes to ecological restoration. Unlike birds and insects, snakes don’t have wings. Snakes are also terrible at crossing roads (probably because they don’t have legs). So, the big question is if you build it, will they come? That is, if you go through the hard work of restoring an old ag field back to tallgrass prairie, will snakes recolonize the site? Dr. Richard King and I tried to tackle this question in a recent publication creatively titled “Responses of Grassland Snakes to Tallgrass Prairie Restoration.” In short, yes, but it’s complicated!  The eastern fox snake (Pantherophis vulpinus) is one of many species that make Nachusa Grasslands their home. Friend to the farmer, this species feeds mostly on rodents. Unfortunately, due to a habit of vibrating their tail (see video at the end), they are often confused for rattlesnakes and killed. Before we dive into what we found, how do herpetologists actually study snakes? It’s not like you can lean against a shady bur oak and listen for the sounds of singing snakes (yes, this is a playful dig at my ornithologist friends). One option is to simply walk around and look for snakes. This is, however, not very effective. Think of how many snakes you’ve stumbled across at Nachusa. Maybe a handful at most, right? Certainly not enough to do some fancy statistics. Nor will snakes stumble into a tiny metal box baited with peanut butter (sorry mammologist friends, I had to make it fair to the ornithologists!). So, what is the intrepid herpetologist to do? We take advantage of a snake’s natural tendency to hide under things, so we employ something called “artificial cover object surveys.” What this means is that we put out things that snakes will hide under (in our case plywood boards and rubber mats), and then go back later and check each one. What does a check entail, you may ask? Great question, and the answer is simple: bend down, lift the board, and then try to grab every snake you see! Simple, but not easy; those little buggers are fast! An unexpectedly large common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) found under a board. Even seasoned herpetologists get impressed by big snakes! Now the nuts and bolts of our study. To address the question of snakes and habitat restoration, we deployed approximately 240 snake boards across 12 restoration units (2–25 years since restoration) at Nachusa. We (ok, mostly Rich) checked each board roughly once a week from May to October from 2013–2016. This resulted in sacrificing our lower backs for science a total of 15,720 times over the four years. (The astute reader may notice the math doesn’t work out perfectly, and that’s because life often gets in the way of checking snake boards!) Was it worth it? You bet! Overall, we caught 1,028 individual snakes of four focal species: 90 plains garter snakes, 112 eastern fox snakes, 347 Dekay’s brown snakes, and 479 common garter snakes. Each snake was given a unique marking so we could identify it if captured again, and we also measured and weighed each snake. We also found a few other species in small numbers. Right off the bat, we see that all four species readily colonized tallgrass prairie restorations at Nachusa, which is great news! We also found that there was no relationship between restoration age and the abundance or occupancy of plains garter snakes, eastern fox snakes, or common garter snakes. That is, newly-restored sites were just as likely to have these species as older restorations. However, older sites were much more likely to have Dekay’s brown snakes than younger sites. This is a really cool finding, as Dekay’s brown snakes are the smallest of the four species (adults rarely exceed 18 inches), and they also have the smallest home ranges. This suggests that smaller species with limited dispersal capabilities might be slower to colonize restorations. Intuitive for sure, but it’s always great to have data! Finally, there was a glaring omission from our snake board data: we found zero smooth green snakes! This was really odd, as the species was once common across northern Illinois, and we found them to be relatively common at nearby Green River Wildlife Management Area. However, snakes can be really hard to find, so the question became, “Are smooth green snakes truly absent from Nachusa, or did we simply fail to find them?” To address this, we took our data from Green River and used a statistical technique called logistic regression to calculate something called a "detection probability". The results? Given our approximately 15,000 cover board checks, we estimated there was a 99.9% chance we would have detected them if they were indeed present at Nachusa. Could we have missed them? Certainly, but it is highly unlikely. So, why are there no smooth green snakes at Nachusa? The most likely explanation is that they simply did not survive in the small remnants at Nachusa prior to restoration. Like Dekay’s brown snakes, smooth green snakes are quite small and are probably not so great at colonizing new areas. In addition, smooth green snakes specialize on eating insects and spiders, and they may be particularly susceptible to insecticide use relative to other species with broader diets. So, if they didn’t survive at Nachusa, crossing miles of roads and ag fields might pose too big of a challenge. Therefore, while a “wait and see” approach might work for other species (such as Dekay's brown snake), captive breeding and translocation may be necessary to establish populations of smooth green snakes at Nachusa. This approach has shown great promise in the Chicago suburbs, and I hope one day to see the tail end of a smooth green snake slipping away into a tussock of little bluestem at Nachusa Grasslands. In conclusion, we found that Nachusa boasts plentiful populations of at least four species of grassland snake, and these snakes are not limited to the remnants, but occur broadly throughout restoration units. Other species also occur, including the eastern hog-nosed snake, eastern milk snake, North American racer, and common water snake. However, the smooth green snake, a species that is common in nearby Green River Management Area, appears to be truly absent at Nachusa. I propose they be considered a candidate for assisted translocation or reintroduction, pending further study, of course. Thanks for reading! Have you seen any snakes at Nachusa? If so, what kind? Let me know in the comments, and feel free to send me an email for snake identification help from Nachusa or anywhere else! Many harmless snakes, such as this eastern fox snake (Pantherophis vulpinus), will defensively vibrate their tails.

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed