|

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry SpringSummer

3 Comments

By Marissa Gorsegner Nachusa Restoration Technician When you look around Nachusa Grasslands in the summer, you can see constant change in the prairie. You see an array of people day in and day out working in the summer heat. Some of these people are the summer restoration crew whose job is to work on the restorative vision of Nachusa. We spent our time working hard at killing weeds to restore the prairie, picking seeds for future plantings and, of course, having fun! Our 2022 summer restoration crew was made up of seven members who never said no to a challenge that presented itself. Working together, we faced these challenges head-on. One issue every summer is fighting the weeds that pop up throughout the prairie. We began early summer with focusing on reed canary and bird’s foot trefoil (BFT). Then we moved onto king devil. Yellow and white sweet clover became the next major focus, with BFT moving right back to the top of the list as seed pods began to pop up everywhere. We also busied ourselves with collecting seeds, collecting more and more as the summer progressed. Seeds such as pussytoes, oxalis, daisy fleabane, sedges, and June grass were some of the favorites to collect. We also learned how to mill seeds, and spent some time during rainy days milling seeds we had collected.

SUMMER CREW

FALL CREW Along with Molly Duncan and Derek Hofland, Noah and Booker joined the fall crew.

By Charles Larry Friends of Nachusa Grasslands Board It was the Greek philosopher Empedocles (c.450 BCE) who first presented the idea of the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. He did not call them elements, but roots, and conceived of these not in terms of the physical properties we associate with the words, but as forms of energies whose various combinations make possible the structure of the physical world. This idea was later amplified by Plato, and then, especially, Aristotle. For the purpose of this blog post, however, earth, air, fire, and water are being used more as a conceit to imaginatively explore the elements as they may (loosely) apply to Nachusa. This exploration, in part, will utilize stories from Greek mythology. EarthHeavy, dense, solid: earth. As Gaia the earth is the foundational mother of all living things. The name Gaia is now associated with many environmental concerns. Is there any North American mammal more evocative of earth than a bison? Massive, strong, brown in color, the bison seems sculpted of earth. Rock: the bones of the earth. Nachusa's rock formations are mainly St. Peter Sandstone, which is composed of sand that once rested on the bottom of ancient seas. Over billions of years this sand sediment compacted and eroded, and after extensive land mass shifts with tectonic and glacial activity, the rock became exposed and left as outcrop. The earth with its layer of soil, giving foundation and nutrients and collecting moisture, provides growing things the necessities of life. The earth establishes a stable environment for plants, animals, and all creatures of the air. AirLight, open, space: air. Air has been called the breath of life. It surrounds the planet in a protective layer and is a requirement for most living things. In The Odyssey, Aeolus, keeper of the winds, put all of the winds except the west wind in a bag and gave it to Odysseus. The west wind would take Odysseus and his men directly to their island home of Ithaca. But the men, thinking it was some treasure that Odysseus was keeping for himself, opened the bag and let loose the winds which drove them far from home, thus taking an additional ten years to reach home after having fought in Troy for ten years. There are times at Nachusa when it seems that bag has been opened on the prairie. The early pioneers, traveling across the tall grass prairie and observing the undulating waves of grasses caused by the wind, called it a "sea of grass." Wind also helps disperse seeds, such as the lithe milkweed seed. Mankind, observing birds and flying insects, dreamed of taking to the air long before it became a reality. Daedalus, who designed the labyrinth imprisoning the Minotaur, himself became imprisoned, along with his son Icarus, to keep the secret of the labyrinth. Daedalus crafted wings made of wax so that he and Icarus could escape. This succeeded until Icarus, in his youthful headiness, flew too close to the sun, melting the wings, thereby plunging him into the sea, resulting in his death. There are times when the air, the sky with its cloud formations seems to be on fire. FireHot, expansive, light: fire. Fire can be both constructive and destructive. In Greek mythology, Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to mankind as a gift, thereby creating technology and civilization. For this act he was punished by the gods by being chained to a rock, where an eagle each day ate his liver, which grew back overnight, only to be eaten again, over and over. At Nachusa, fire usually means a prescribed burn. The prairie, like the Phoenix, needs fire for renewal. Our most pervasive source of fire/light is the sun. Sunlight is needed for plants to photosynthesize. Illuminating everything, the sun can seemingly perform magical transformations, such as becoming like molten gold on water. WaterCold, contractive, fluid: water. Most of our planet is covered by water. Perhaps the most versatile of the elements, water can exist in different states. As a fluid it is water, as a gas it is steam or mist, and as a crystalline solid it is ice. In Greek mythology it is Poseidon who rules the waters. Better known by his Roman name: Neptune, he is the Old Man of the Sea, covered by scales and holding a trident. Poseidon is the protector of all who live in the waters of the earth. It is Nachusa's ponds and streams which provide the life-giving element to all the creatures at home here. The most common source of water at Nachusa is, of course, rain. Life-nourishing rain sweeps across the prairie and savanna in storms. In winter, snow often blankets the land with needed moisture. Water: the lifeblood of the earth. If you would like to volunteer at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays.

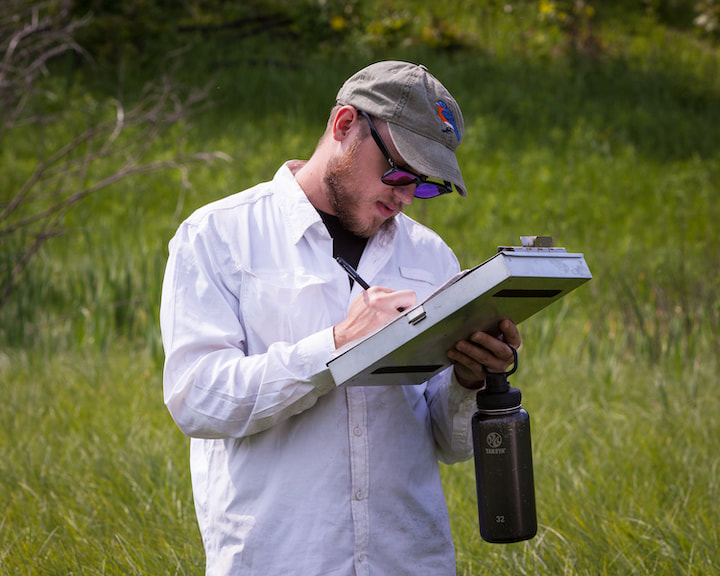

By Luke D. Fannin PhD Candidate, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH Grass-eating, or graminivory, as it is called by scientists, is a strange behavior. At the outset, grasses, at least compared to the many plant foods that humans consume regularly, look unappetizing; they are tough to chew, they are full of fibers that make them difficult to digest, and they are often covered in dust and sand from growing close to the soil surface. But for many mammals, ranging in size from tiny voles (20-24 grams) all the way up to gigantic white rhinoceroses (2400 kilograms), grasses are dietary staples, and these so-called “grazers” (grass-eating mammals) are pivotal in Earth ecosystems. Nachusa Grasslands is home to one of North America’s most important grazing mammals, the bison (Bison bison), which eats grasses in most months of the year. But if grasses are such difficult foods to eat, how do bison–let alone any other mammals–eat them? As it turns out, bison have a few tricks up their proverbial sleeves as it pertains to eating grasses. For starters, bison are ruminant mammals, which means they have highly specialized stomachs that allow them the ability to regurgitate and then re-chew partially digested plant foods. Think of how a domestic cow eats; the cow first swallows a bite of food but then proceeds to regurgitate that bite of food and chew it again, and again, and again… until finally those food particles are small enough to pass through the rest of the digestive system. With each subsequent swallow, foods are bathed in stomach juices teeming with bacteria, which also help to weaken the structural integrity of fibrous foods and liberate nutrients. This digestive trick is incredibly helpful for bison, as it allows them to digest grasses in a way that humans cannot. Secondly, bison are endowed with highly specialized teeth, termed hypsodonty. Unlike the surfaces of our own teeth, which fully poke out of our gums when they erupt, bison’s teeth emerge in a piecemeal fashion over the course of their lives, meaning that they usually have more teeth hiding within their skulls at any given point in time. A good analogy for how bison teeth work is the lead found in the tip of a mechanical pencil: while there is always lead at the pencil tip exposed for writing, there is far more lead stored within the pencil that emerges to eventually replace the used-up lead after writing is finished. Hypsodonty is thus a useful trait for Nachusa bison because most grass plants are also abrasive (see below), meaning they remove tooth surface, or enamel, during chewing. Hypsodonty allows bison to continuously provide new replacement tooth surface over the course of their lives, allowing them to keep eating grass plants without having to worry about completely losing their teeth in the process (although they are not actively growing teeth, and this excess amount of tooth eventually wears out in old age).  Bison teeth are hypsodont, meaning that the dental crowns are tall and most of this length is stored within the bones of the face and jaw. This trait provides a hidden reservoir of tooth material that can be pushed out when the surfaces of the teeth wear, allowing for tooth function to be preserved in the face of extremely abrasive conditions. In addition, when bison teeth wear, the enamel forms elaborate cutting surfaces with a harder underlying tooth material (referred to as dentin, which is the brown material contrasted against the pearly-white enamel on the tooth surfaces). These elaborate cutting surfaces help bison mince plant foods. But with all this talk of bison traits to eating grass, it is easy to view the grasses themselves as passive players in this story of herbivory at Nachusa. But can grasses fight back? My own work at Nachusa Grasslands seeks to answer this question with one plant trait that may act as a defense against herbivory . . . silica levels. While we often think of silica as being a component of our modern technology (e.g., in computer chips), silica is also one of the most abundant minerals in Earth’s soils. Grasses, in turn, uptake silica into their own tissues during growth, where it usually gets deposited into silica bodies called phytoliths. The function of silica accumulation in grasses is debated, but one thought is that it provides a defense against defoliation (i.e., the removal of leaves). As suggested previously, grass plants are abrasive, and it is the silica in grass leaves that hypothetically works to remove enamel. As such, high levels of silica in grass leaves may deter mammalian consumers from eating them — for risk of damaging their teeth — helping to prevent defoliation. Silica also works to stiffen plant leaves, making them more difficult to chew and digest, while also further inhibiting microbial digestion in the digestive tract. Thus, silica be an inducible defense for grasses, wherein a re-growing grass plant responds to previous herbivory by increasing silica uptake to prevent severe defoliation in the future. But silica has other important functions in grass plants that are unrelated to herbivory. For example, increased silica uptake in grasses is also important for relieving environment stresses related to both high temperatures and low water availability. Therefore, it remains challenging to determine whether the high silica levels found in some prairie grass plants are primarily a response to intense herbivory pressure (i.e., from roaming bison) or are instead a plastic response related to changes in local environmental conditions that may increase growing stresses.  Bison at Nachusa can exhibit immense herbivory pressure on the local grassland community and repeat herbivory at certain locations can create what are termed “grazing lawns”, where grass plants are maintained in a short-statured state as compared to surrounding vegetation. It remains unknown whether the grass species within these “grazing lawns” at Nachusa possess higher silica levels in their tissues than similar species within exclusion plots, but previous work on the African Serengeti has suggested that grasses in such features are more silica-rich than similar species under less extreme herbivore pressure. My current work at Nachusa Grasslands seeks to shed light on this mystery. By taking advantage of bison exclusion plots set up across the lands of the reserve, I can compare the silica levels of different grass species (and other related traits, such as photosynthetic pathways, leaf toughness, and nutrient levels) in locations where they have experienced almost a decade of bison herbivory (2014 – 2021) to those same species in exclusion areas where bison herbivory has been much less intense or non-existent. My hope for my continuing work at Nachusa is to disentangle the various factors that may influence silica levels in various grass tissues of prairie plants and, by extension, in the diets of Nachusa bison. My overarching goal is to figure out if re-introduced bison are helping to change the functional traits of grasses growing within the Nachusa reserve, and if so, what this might mean for plant community structure and resilience moving forward.  Exclosure or herbivore exclusion plots are key to testing hypotheses regarding inducible plant defenses and bison herbivory at Nachusa Grasslands. The bison have access to the plants on the left side of the photo, but in the right side of the photo begins the exclosure, a space that is completely isolated by fencing and the bison cannot enter. Notice the taller vegetation in the exclosure. Numerous exclosures are found throughout the bison unit.  The author (L.D. Fannin) in his mobile lab processing collected grass plants in the field at Nachusa in June 2021. To prevent molding, grass plants need to be dehydrated before transport, and the food dehydrator at the far right allows for the dehydration of plant remains to occur quickly before plants are then ground and stored with desiccant. The author is currently analyzing these collected plant parts for their silica content at Dartmouth.

Luke Fannin was a 2021 Scientific Research Grant recipient from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Interested in supporting Nachusa's science? Just designate your Donation to "Scientific Research Grants."

By Elizabeth Bach Research Scientist at Nachusa Grasslands, The Nature Conservancy Nachusa has experienced several ups and downs in 2021. COVID-19 continued to bring challenges and require flexibility. We celebrated the opening of our new equipment barn, but we also grieved the loss of naturalist Wayne Schennum. Wayne conducted plant and insect surveys at Nachusa throughout his long career and was actively working on a survey of leaf beetles prior to his passing this summer. Amid this uncertainty, the Nachusa science community managed to accomplish a lot.

Pete Guiden started 2021 strong with the publication of Effects of management outweigh effects of plant diversity on restored animal communities in tallgrass prairie in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This is one of the top three scientific journals in the world; it is a major accomplishment for Pete and his co-authors in the Holly Jones and Nick Barber labs. It is significant for a Nachusa dataset to contribute to global scientific advancement in this way. They found management-driven responses were more common (and stronger) than plant-driven responses. Restoration age was the main driver of management effects, followed by prescribed fire. Both plant diversity and active management were critical to restoring animal biodiversity. You can learn more from Pete’s blog post. Another significant Nachusa publication was Twenty years of tallgrass prairie restoration in northern Illinois, USA, published in Ecological Solutions and Evidence as part of a global special issue on the UN Decade on Restoration. Elizabeth Bach analyzed 20 years of plant survey data from permanent transects set up by Bill Kleiman. Plant communities on native prairie remnants have maintained or increased plant diversity, including rare plants. Savannas maintained similar levels of plant diversity, but plant communities shifted from understories dominated by brush to herbaceous plants, including native grasses and flowering plants. The special issue on the UN Decade on Restoration also featured a paper from Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar and Sean Griffin. Variation in prescribed fire and bison grazing supports multiple bee nesting groups in tallgrass prairie showed that a mixture of fire and grazing on the landscape encouraged diverse bee communities by promoting bees with different nesting habits. Nachusa bees were primarily ground-nesting (90% of observed species), but stem/hole nesters (3.6%) and large-cavity nesters (6%) are also important parts of the community. This team also published Bee communities in restored prairies are structured by landscape and management, not local floral resources in Basic & Applied Ecology. Large-landscape restorations were positive for bees, as the relationships with floral diversity observed in previous work in small, isolated prairies did not hold up at Nachusa. Several Nachusa insect studies were published in 2021. Michele Rehbein, who surveyed mosquitoes at Nachusa for her PhD work at Western Illinois University, published A new record of Uranotaenia sapphirina and Aedes japonicus in Lee and Ogle Counties, Illinois. Both these mosquitoes are new records for the area and contribute to broader understandings of mosquito communities in Illinois generally. Azeem Rhaman published Disturbance-induced trophic Niche shifts in ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in restored grasslands, summarizing his MS research with Nick Barber at San Diego State University. He found ground beetles consumed a wider range of food sources in areas with bison grazing, particularly with both grazing and fire. Meghan Garfinkel, who earned her PhD from University of Illinois – Chicago, specifically examined insects present in bird diets. Using faecal metabarcoding to examine consumption of crop pests and beneficial arthropods in communities of generalist avian insectivores, published in Ibis, was the first study to leverage next-generation DNA sequencing to analyze diets of entire bird communities. Birds consumed more herbivorous arthropods (plant-eating bugs) compared to carnivorous arthropods (bug-eating bugs). Heather Herakovich published two papers on birds this year. In Impacts of a Recent Bison Reintroduction on Grassland Bird Nests and Potential Mechanisms for These Effects, she found that bison presence did not impact nesting density or vegetation structure, but nest success increased in the first two years after reintroduction. Heather evaluated birdsong to passively survey communities in Assessing the Impacts of Prescribed Fire and Bison Disturbance on Birds Using Bioacustic Recorders. This dataset showed that having a mix of recently-burned, unburned, and grazed habitat in the landscape supported diverse bird communities, as different species have different habitat preferences. It was a strong year for animal publications from Nachusa. Rich King and graduate students Monika Kastle and Callie Golba published two papers about their work on Blanding’s turtle recovery in northern Illinois, including the Nachusa population. Blanding's Turtle Demography and Population Viability focused on modeling needs for Blanding’s turtle populations to sustain themselves. Blanding's Turtle Hatchling Survival and Movements following Natural vs. Artificial Incubation reported on the results from the 2020 release of Blanding’s head-start hatchlings at Nachusa and other sites. Survival rates were variable across the populations, and research continues at Nachusa to find the most effective ways to protect these turtles. Publications of threatened and endangered species extended to plants as well. Katie Wenzell, who earned her PhD from Northwestern/Chicago Botanic Gardens, published Incomplete reproductive isolation and low genetic differentiation despite floral divergence across varying geographic scales in Castilleja in the American Journal of Botany. This work examined the genetic relatedness and floral variability of Castelleja sessiliflora (downy paintbrush) and C. purpurea (prairie paintbrush or purple paintbrush) across their geographic ranges. Both species are evolving, but C. sessiliflora is exhibiting genetic differentiation, whereas C. purpurea is exhibiting differences in flower shape without genetic changes. These are two different mechanisms driving similar evolutionary outcomes. Timothy Bell and colleagues explored population trends in the threatened eastern prairie fringed orchid in Environmental and Management Effects on Demographic Processes in the U.S. Threatened Platanthera leucophaea (Nutt.) Lindl. (Orchidaceae). They found regular burning and wet weather lead to greater blooming populations for the orchid. To evaluate landscape-level plant community and soil characteristics, Ryan Blackburn tested aerial imaging from drones in Monitoring ecological characteristics of a tallgrass prairie using an unmanned aerial vehicle, published in Restoration Ecology. Drone images did an adequate job of evaluating grass cover and mean dead plant cover, but more work is needed to refine this method. Scientific accomplishments at Nachusa are making strong contributions to both scientific understanding and on-the-ground conservation and restoration efforts. Thank you all for being part of this. None of this could happen without the collaboration of scientists, volunteers, donors, The Nature Conservancy, and Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Many of the 2021 researchers were supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. By Connor Ross Nachusa Restoration Technician Rebounding from the unusually short 2020 field season, the Nachusa restoration crew hit the ground running in 2021. It’s amazing what you can do when you have a couple extra weeks and a full crew on hand! Each year presents its own challenges. Last year I wrote about how the infamous (and unfortunately, still ongoing) pandemic disrupted the burn season. A record fire regime this year ensured the crew didn’t have to trek so much through unburned plots of land – that’ll really put your knees and hips to work! I also discussed the extremely wet spring of 2020. In a reversal of fortune, we ended up working during a drought year for 2021. Creek levels in late May were as low as they should’ve been in August, and most storms conveniently split to the north or south (often both) before they could supply Nachusa with some much-needed water. This drought meant the crew faced a mixed bag of effects: a lower invasive plant population and some seemingly confused natives. These “confused” natives often seemed to bloom and go to seed earlier than expected from previous years. New England asters started blooming at the very end of June! As we face the transition to fall, the focus of the crew has been mainly on seed collecting, as weed killing season drew to a close. We swept certain units no less than four times this season for birdsfoot trefoil, tore sweet clover out of the ground on remnant knobs, plucked king devil heads before they could go to seed, and even patrolled the roadside ditches, spraying yellow iris and scything parsnip. The crew feels incredibly lucky to have the new Morton building to process seed. Because of this, we’ve been able to collect and then subsequently mill record amounts of seed, blowing our 2020 numbers out of the water. As of this writing, we currently have milled over 250 pounds of seed from over 40 species. We’ve been able to collect some seeds we missed last year, such as the seed pods of blue flag iris, which explode and shower seed everywhere in the vicinity when ready. We’ve seen all sorts of seed diversity: sticky catchfly seeds as small as a grain of sand, hairy beardtongue seeds that smell like roadkill, delicately fluffy dwarf dandelion seed, black-eyed Susan seed that digs into your skin like fiberglass. They’ve been harvested from every part of the preserve and in any sort of environment: golden Alexander from a classic mesic prairie, sedges that require a good pair of muck boots to collect, and fameflower from the sandy, desert-esque remnant knobs of Nachusa. As the fall season kicks into gear, the crew will continue collecting even more species from all across Nachusa in preparation for future restoration projects. The crew has worked hard this season in all sorts of conditions. We can attest to some bone-rattling days in May where we wore two layers under our rain jackets. And we’ve also labored through unusually hot June and August days with heat indexes topping 115 degrees Fahrenheit. We’ve killed sweet clover during rainstorms and been blasted with 40 mph gusts as we picked seeds. At times, the restoration technician position can be physically demanding and exhausting; hauling a two gallon herbicide pack for eight hours on the prairie is no joke! But time and time again it has proven incredibly worth it. We’ve seen the 2020 planting come to life this year, and already some of the seeds we collected last year have sprouted up: black-eyed Susan, white wild indigo, partridge pea. It has proven especially worth it through our wildlife encounters. A mink on her morning pond patrol on a cloudy day. Rescuing a cliff swallow with twine wrapped around its toes. Listening to sandhill cranes uttering their melodious primeval cries. Scaring up more frogs in a few minutes than you could count on your hands and toes. We even found an endangered Blanding’s turtle whose radio tracker had died. And of course, we’ve had plenty of encounters with bison. As rut season begins, the roars of the bull bison almost sound akin to lions on the Serengeti. We’ve watched adult bulls size each other up, and yearling bulls jostle each other around in imitation of their elders. We’ve also seen a more tender side to the bison, as one crew member, Zach, was lucky enough to come upon a cow that had just given birth in late June. The calf couldn’t even stand up yet! All in all, it’s been an incredibly successful summer at Nachusa that has proven worth the hard work. Nachusa is truly a place like no other, and we all feel lucky to be a part of it. Meet the Crew

By Becky Jane Davis Nachusa Grasslands Butterfly Monitor For several years, I’ve been trying to start butterfly monitoring with the Illinois Butterfly Monitoring Network (IBMN). Everything finally came together this year. Recently I did my first butterfly monitoring at Nachusa Grasslands. Butterfly monitoring consists of counting butterflies by species, in a specific route, throughout the season. This first year, I need to identify only 25 species of butterflies. Forty years ago, I could identify more than that, but I'm a bit rusty. So, I walk at a regular pace, scanning the area, left and right on the trail, spotting butterflies. As I see one, I identify it and mark it on my field report. When I’m finished, I enter my findings in the database. It sounds easy and straightforward but my first time out, I identified about half. The rest were noted as “unknown butterflies,” so I have some learning and growing ahead of me. Things they don’t teach you in butterfly monitoring training: 1. How do you count each Monarch only once? They go here, over there, cross over the trail, and then you wonder, did I already count you? 2. Prairie plants are dense and tall. Those little butterflies can dart across the trail and into the plants and disappear before I can even see the markings or colors. 3. You need to protect yourself from ticks. That means bundling up head to toe in insect repellent-treated clothing, wearing hiking boots. Take a walking stick for uneven ground, don’t forget binoculars (if you can get them out and focused fast enough). There must be a simpler way! 4. It is good to know what a species looks like both flying and resting, but what about moving so fast, never resting, and not at an angle to fully see all four wings at once, as in the photos? 5. Back when I knew all the different species, it was because I caught them, put them in a kill jar, mounted them, and used a detailed key to identify them. No guessing! When my route is done, I have a short 10-15 minute walk back to the parking lot that allows me time to linger, get out my iPhone for a few photos, or get my good camera out to capture prairie life. I hope to get back to butterfly monitoring at least five more times this summer, hopefully more. Weather is an issue, as is distance, because I chose a location an hour away from my home. I like going to Nachusa, but it is at least a 3 hour commitment to monitor and I need to leave room in my days and flexibility so I can make that trip. Weather has not been helpful this last month. Rain, wind, and cloudiness are not good for butterfly sightings. In fact, I have rules to follow: at least 70 degrees, partly cloudy to full sun, little wind to moderate wind, and no rain. The last two weeks didn’t give many days to choose from. But I will continue and try to get more of my own photography adventures in as well. The native grasslands and prairies offer so many opportunities for interesting captures. I’m looking forward to what I can share in future blogs! Butterfly monitoring data from 7/17/2021: The route was about 50 minutes. Temperature: 77 degrees Wind speed: 9 mph. The wind was stronger at the end of the route. Sky: partly cloudy

Who are the citizen scientists, and how can I become one? Nachusa’s citizen scientists are composed of community volunteers who are passionate about their subject and want to contribute to scientific research. Do citizen scientists need prior experience or a science degree? No previous experience or scientific background is needed to volunteer, although some monitoring programs require approved initial and/or refresher trainings. Some citizen scientists may desire to seek further training and acquire new skills, while others can assist trained citizen scientists to learn the monitoring process. What citizen scientist opportunities are available at Nachusa?

How can I become a citizen scientist at Nachusa? It’s simple, just sign up on the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website. To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends of Nachusa Grasslands can also be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

By Peter Guiden, PhD Post-Doctoral Fellow, Northern Illinois University An ecosystem is a complex, wonderful thing. It represents many species of plants, animals, and micro-organisms interacting with each other and the air, soil, and water. It is greater than the sum of its parts. And in restoration ecology, a central goal is to put degraded ecosystems back together. However, doing so is often a challenging process—that same complexity that makes an ecosystem beautiful can also make it difficult to manage. A logical starting point is to restore the native plant community. Plants play so many important roles in an ecosystem: they provide habitat and food for animals, they exchange nutrients with microorganisms, help develop soil, and link aboveground and belowground worlds. Every plant species plays a different role in the environment, so land managers often aim to restore as many native plant species as possible, leading to high biodiversity. At Nachusa, prescribed fire and bison reintroduction are used to meet this goal, knocking back the most competitive plant species and allowing many species to coexist. Hopefully, these diverse plant communities support many diverse animal species…right? It turns out that this question isn’t often asked. It’s difficult to answer, because scientists often specialize on one group of organisms, and individually lack the tools to measure how the ecosystem as a whole responds to management. Answering this question requires assembling an Avengers-style team of researchers, who can complement each other’s interests and expertise, at the same place and time. Luckily, the Nachusa community provided an opportunity for this to happen. Through collaboration between Nachusa, Dr. Holly Jones’ Evidence-based Restoration Lab at Northern Illinois University, Dr. Nick Barber’s Community Ecology & Restoration Lab at San Diego State University, and Dr. Rich King’s lab at Northern Illinois University, we could start to look at links between plants and animals. Each of these groups brings a unique skill set to the table. Dr. Jones and her students study plants and small mammals such as wild mice and voles. Dr. Barber and his students study plants, ground beetles, and dung beetles. Dr. King and his students study larger wildlife, such as snakes. Each of these groups has collected data on these animal communities over the past decade at Nachusa, including how many species occur in these study sites, and in what abundance. This gave us an opportunity to combine our data, and ask some broad, general questions about how restoration works. Here’s a link to the study we did, if you’re interested in the technical details. We wanted to know whether the areas with the most plant biodiversity also had the most animal biodiversity, or if something else explained patterns in animal communities. If plant and animal biodiversity were linked, that would suggest that restoring diverse plant communities may lead to recovery across the ecosystem. However, if the link between plant and animal biodiversity isn’t strong, other management strategies may be needed to boost native animal species. We found that in general, the best explanation of animal biodiversity had little to do with plant biodiversity. For example, small mammal communities were most diverse in areas that hadn’t been burned for a few years, because species like voles make their habitat in thatch (dead plant litter). Similarly, snake communities were most diverse in older restorations, because certain species take a relatively long time to colonize new habitats. This isn’t to say that plant biodiversity is unimportant for animals: there were many cases where plant and animal biodiversity were linked. Small mammal communities were more diverse in habitats with a rich mixture of forbs and grasses, and the most diverse ground beetle communities were found in areas with many plant species. But on average, the effects of management on animal biodiversity were six times stronger than the effects of plant biodiversity. Why didn’t we find a strong link between plant and animal biodiversity at Nachusa? One potential explanation is our choice of study species. Snakes and beetles are carnivorous, while small mammals are opportunistic omnivores, eating both plants and animals. Perhaps animals that are strict herbivores (especially insects with very particular diets) would have been more responsive to plant diversity. But for our animals, the age or structure of the plant community seemed to be more important than the number of plant species present. It’s also important to point out that maximizing animal biodiversity may not be the most important goal in a restoration project. Protecting rare species (like the rusty patch bumblebee) or species that play an especially important role in the ecosystem (like large dung beetles that eliminate large volumes of bison dung) may take center stage. In cases where restoring animal biodiversity is important, however, it may be necessary to consider how land management affects both plants and animals. One key take-home message of this study is that restoration really works. Through the hard work of land managers, volunteers, and scientists, it is possible to recreate diverse plant and animal communities in a very agricultural landscape. While we are constantly trying to learn more about how exactly these species respond to restoration, it is important to reflect on these successes. Ecosystems continue to be mysterious in many ways, but understanding a little bit more about them may help preserve their majesty and diversity for the future. Pete Guiden's ongoing research on restoration ecology is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

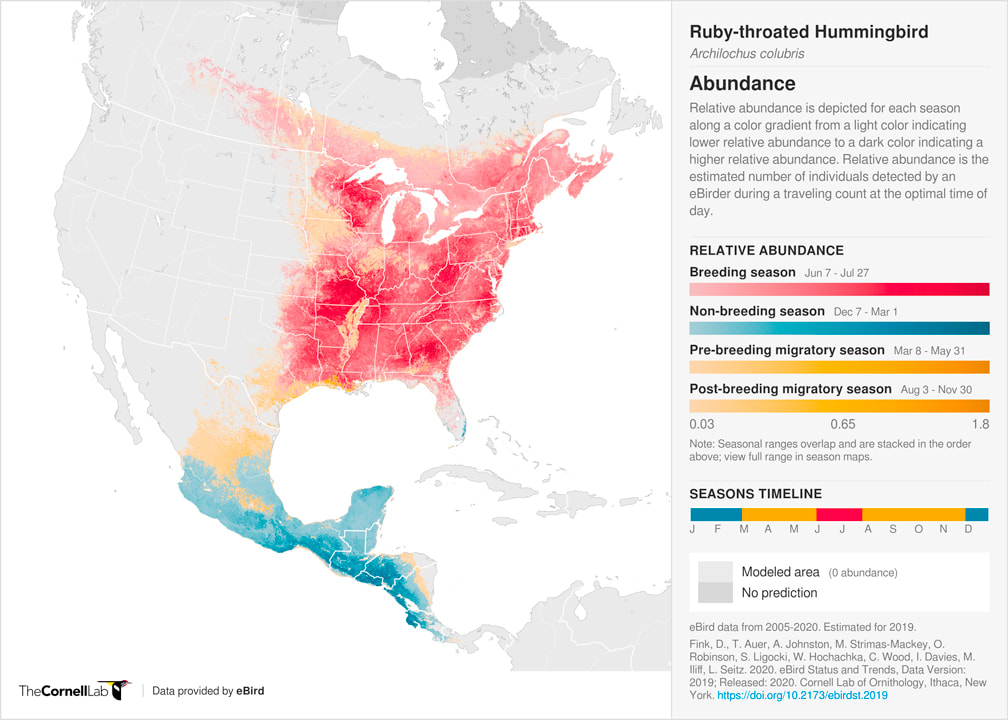

By Antonio Del Valle MS Student Spring has arrived, and with it we are in the middle of experiencing one of the many natural marvels at Nachusa: spring bird migration. Certain species of birds fly south for the winter to warmer latitudes (Florida, Mexico, and even South America) and then return to breed in northern latitudes during the summer. The specific reasons for migration depend on how far birds migrate. Short-distance migratory birds head south mainly for food. When the growing season ends here in Illinois, insects, seeds, and other food sources dwindle, which drives birds south to locations where food sources and open water are readily available. The logic and theory behind long-distance migrants (those that travel to Central and South America) appears to be more complex. According to a concise article by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the history of long-distance migration appears to be rooted in evolution. Birds that evolved to migrate long distances gained an advantage over birds that stayed in the tropics by producing more young via seasonally increased day lengths and food availability in northern latitudes.  Yellow-rumped warblers (Setophaga coronate) have been passing through northern Illinois over the past couple weeks. These warblers over winter in southern US states and Mexico, and they breed as far north as Alaska and Newfoundland. They can be found this time of the year in the wooded areas of Nachusa, including Stone Barn Savanna. By the end of May they will have moved north to their breeding grounds. Although migration occurs twice annually (both in the spring and fall), it offers a chance to see some interesting bird species that do not spend much time in this area. Starting in March, we started to see a number of birds passing through Nachusa on their way north. Notably, whooping cranes (Grus americana) were observed among the larger groups of sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis). These whooping cranes are a part of a recovering population of cranes that breed in central Wisconsin and over-winter in Florida. Thanks to conservation efforts, these federally endangered birds have started to recover (increasing from about 20 birds in the 1940s to about 600 today). Conservation efforts still continue for whooping cranes, and it is certainly a special treat to have them stopover at Nachusa. Besides cranes, high numbers of waterfowl were observed occupying the new wetland scrapes by the visitor center. In March and April there have been diving duck species observed, such as bufflehead (Bucephala albeola), ring-necked duck (Aythya collaris), and scaup. Here in April we are observing many more dabbling duck species like blue-winged teal (Spatula discors), hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), northern shoveler (Spatula clypeata), and wood duck (Aix sponsa). Though these species are visiting Nachusa now, many of them will continue northward to breeding grounds in the northern lakes of Wisconsin and Canada. As we progress through April into May, we will see more of our medium and long-distance migrants. These birds are making a long trek from Central and South America, sometimes flying long distances at once. One salient example of long-distance migration is the route of some ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris). These tiny birds are known to fly directly over the Gulf of Mexico from the Yucatan Peninsula to southern United States. That’s a 500 mile flight in approximately 20 hours! Though I haven’t seen any hummingbirds yet this spring, I bet there will be some in the area soon. As spring progresses, flowers bloom, and birds will continue moving northward. I hope you will be able to enjoy the wonders of Nachusa Grasslands and bird migration this spring. Citations & Resources:

Tony Del Valle's grassland bird research was supported in 2020 with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy.

To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. By Dee Hudson There are actually many mammals and birds active during the cold weather. What animals might you be able to see this winter? Today I’ll feature a few larger mammal species that I think you will enjoy and be most likely to see during a visit. I will also give you tips on where to look for these winter animals. Bison There is a very popular animal that draws the attention of most of our visitors, and that is our national mammal, the bison. The Nature Conservancy is committed to keeping the bison as wild as possible, so besides some minimal veterinary care during the yearly roundup, the bison breed, birth, feed, and care for themselves without human intervention. Our bison roam across 1500 acres of rolling landscape, so they may not always be visible. For your best chance to see the bison, bring a pair of binoculars and begin your search from the Visitor Center, an open-air covered pavilion that offers outstanding views of the surrounding grasslands, as well as the southern bison unit. Be sure to pick up a hiking brochure there, for the map inside indicates the bison unit locations. Many visitors can also experience a close-up view even from their cars. Just be sure to pull off to the side of the road and turn on your hazard lights. CAUTION: When a lot of snow is present, it is difficult to find parking or a pull-off. Be safe! Also, please be considerate of Nachusa's neighbors, of their property and road use. A six-foot fence surrounds the bison units. For visitor and bison safety, there is no admittance inside these bison units, by foot or by vehicle. Visitors must stay 100 feet from the bison at all times, even when separated by a fence. The bison look tame and gentle, but they are wild and unpredictable animals. Keep in mind that the adults weigh 1000-2000 pounds, are very agile, and can quickly turn and accelerate to 30+ miles per hour. Deer The white-tailed deer is another large mammal often seen at the preserve. Look for them to gather in the early morning or right before sunset. They can even be seen grazing near the bison herd. The deer enter and exit the bison units quite easily, either leaping over the fences or, more often, going under. The fence does not go completely to the ground, and this allows other animals to come and go. The deer tracks are very recognizable. They look like upside down hearts. Beaver Nachusa has beavers throughout the preserve, for these masters of engineering have been drawn to the restored wetland habitats. In winter the beavers are not hibernating, but are snuggled inside their well-insulated lodges. They have stashed a food cache of small twigs and branches in the mud at the bottom of their pond, and they use their lodge’s underwater entrance to access the supply throughout the winter. The water is not too cold for them, even in the coldest Illinois winters, for they have a thick and very warm winter coat. In January they may begin to mate, with their young born in springtime. While the water is frozen, the beavers are unlikely to be seen. However, evidence of their presence in the landscape certainly can, if you know where to look. If you look north from the Visitor Center you can spot the lodge in the restored wetland. It looks like a mound of sticks, with some plants growing on top. Other signs of beaver presence to look for are gnawed trees and beaver stumps.

Red Fox A fox’s fur is so warm that it has no problem curling up on the snowy ground. If its nose becomes too cold, the bushy tail wraps around and makes a great facemask. In the winter, the fox will mainly eat other mammals, such as rabbits and rodents, and of course, it won’t pass up any carrion. In Illinois mating occurs during the winter months, mainly January and February. The young will be born in an underground den in March and April. Look for fox in the prairies and along the woodland edges, and it’s best to begin your search close to sunrise or sunset, because they are mainly nocturnal. Opossum The opossum is the only marsupial species (a mammal with a pouch) native to Illinois, and also to North America. That alone makes this mammal interesting and unique. Then you see that they have an opposable toe and a nearly furless prehensile tail, used to grasp things and climb. With such a naked tail, it might be expected that they hibernate during Illinois winters, but they do not. However, they do stay in their dens during really cold weather, venturing out on warmer winter days. Since opossums are omnivores, winters at Nachusa provide a lot of small mammals to eat; they also eat a lot of road kill (and then occasionally become road kill themselves). For shelter, they may find a hollow log or use one of the stacked brush piles. Opossums are nocturnal, so they’re most likely to be seen in the early morning or before sunset. Look for opossums in Nachusa’s wooded areas near ponds and creeks, for they prefer to have a den near water. Coyote Many Nachusa volunteers have enjoyed a choir of coyote voices during the nighttime hours — yips, barks, and howls — so many communicating at once, that it is hard to tell how many are present. Coyotes are very active at Nachusa during the night, probably feasting mainly on the preserve’s rabbit population, as well as other small mammals. As with many of the other animals discussed, for the most success, look for the coyotes in the early morning hours or before sunset. Look for them running along the vehicle tracks that course through the units. As seen by the coyote footprints and scat, humans are not the only mammals that like to use these vehicle tracks. Come visit the preserve this winter and enjoy Nachusa’s wide-open spaces and special creatures. Let us know in the comment section whether you see any of these mammals. Please visit the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website for the preserve's full mammal inventory list.

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed