|

By Kirk Hallowell and Mary Meier Nachusa Grasslands Volunteers Each year, volunteers commit over 8,000 hours of service to the restoration efforts of Nachusa Grasslands. Volunteers harvest seeds, keep invasive species at bay, assist in scientific research, tend prescribed fires, and perform a myriad of other tasks essential to the restoration process. Volunteer projects must be supported by equipment, herbicide, contract services, and other resources needed for success. Fortunately, the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation empowers volunteers by providing grant funds as a match to local dollars raised and labor donated. Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program awards are used to purchase equipment, herbicide, and services necessary to make these volunteer activities possible. According to its website, “ The Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation (ICECF) was established in December 1999 as an independent foundation with a $225 million endowment provided by Commonwealth Edison. Our mission is to improve energy efficiency, advance the development and use of renewable energy resources, and protect natural areas and wildlife habitat in communities all across Illinois.” (@illnoiscleanenergycommunityfoundation) The Illinois Community Foundation will award Friends of Nachusa Grasslands a grant of up to $30,000 if we fulfill requirements under several categories between May 1, 2023, and April 30, 2024:

Under the leadership of project coordinator, Kirk Hallowell, Friends has chosen two sites at which to focus volunteer hours and grant resources for their current stewardship project: Nachusa’s Big Jump Unit and the Holland Savanna Unit. Both areas are infested with invasive shrubs, including autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) and amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), two of the most tenacious foes that Nachusa’s volunteers battle. On its "Where We Work" web page, The Nature Conservancy explains, “Autumn olive is a problem because it outcompetes and displaces native plants. It does this by shading them out and by changing the chemistry of the soil around it, a process called allelopathy. Loss of native vegetation can have cascading effects throughout an ecosystem, and invasive species are one of the major drivers for a loss of biodiversity.” According to a Friends of Nachusa Grasslands blog post by Scientific Research Grant recipient Kaleb Baker, “Amur honeysuckle is an invasive shrub that flourishes along forest edges and in open woodlands such as those at Nachusa Grasslands. Amur honeysuckle shades out native flora with its early leaf-out and prolonged leaf retention, and when left uncontrolled, it can produce a near monoculture, threatening biodiversity.” Some of the ICECF funds already awarded have been invested in herbicide effective in eradicating autumn olive and amur honeysuckle. Volunteers treat the plants using backpacks and handheld sprayers. The next facet of the Big Jump project is to cut down and stack hundreds of non-native trees to make room for prairie restoration. This task that requires heavy equipment owned and operated by an external tree service contractor. ICECF grant funds will also be used to pay for the machinery and professional tree fellers. Kirk, who also serves as steward of the Holland Unit, offered, “It is exciting to know that the efforts of our volunteers empowered by the ICECF grant resources will make a lasting impact on our efforts to control amur honeysuckle in the Holland Savanna.” An additional challenge for the Holland Unit is that the parcel is dominated by cool weather grasses, including rye and fescue, which are typically resistant to overseeding efforts to establish native prairie plantings. In the second half of the ICECF grant period, we will experiment with preparation methods using herbicide to loosen the grip of the dominant grasses and allow overseeding of native plants to take hold. During the fall months, volunteers also helped collect seeds from the preserve for enhancing our prairie plantings. Our long-term goal is to establish a diverse prairie planting on both the Big Jump and Holland Savanna sites providing for long-term weed management and suppression of non-native shrubs and trees. Ongoing stewardship efforts, including volunteer labor, herbicide application, and controlled burns, will gradually help integrate the target areas into the surrounding habitat. The Friends Social Media Team uses Facebook, Twitter/X, Instagram, and our website to promote volunteer opportunities. You can also follow Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation’s Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program on Facebook and Twitter/X to learn more about the Foundation. #CSgrantsIL #NAicecfdn How Can You Help Friends Earn the ICECF Stewardship Grant?

Volunteer for a Thursday or Saturday brush clearing workday — check SignUpGenius for the schedule. Meet at Nachusa’s Headquarters Barn before 10 am and be ready to restore habitat. If you have any questions about the workdays, check the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website.

0 Comments

By Marissa Gorsegner Nachusa Restoration Technician When you look around Nachusa Grasslands in the summer, you can see constant change in the prairie. You see an array of people day in and day out working in the summer heat. Some of these people are the summer restoration crew whose job is to work on the restorative vision of Nachusa. We spent our time working hard at killing weeds to restore the prairie, picking seeds for future plantings and, of course, having fun! Our 2022 summer restoration crew was made up of seven members who never said no to a challenge that presented itself. Working together, we faced these challenges head-on. One issue every summer is fighting the weeds that pop up throughout the prairie. We began early summer with focusing on reed canary and bird’s foot trefoil (BFT). Then we moved onto king devil. Yellow and white sweet clover became the next major focus, with BFT moving right back to the top of the list as seed pods began to pop up everywhere. We also busied ourselves with collecting seeds, collecting more and more as the summer progressed. Seeds such as pussytoes, oxalis, daisy fleabane, sedges, and June grass were some of the favorites to collect. We also learned how to mill seeds, and spent some time during rainy days milling seeds we had collected.

SUMMER CREW

FALL CREW Along with Molly Duncan and Derek Hofland, Noah and Booker joined the fall crew.

By Connor Ross Nachusa Restoration Technician Rebounding from the unusually short 2020 field season, the Nachusa restoration crew hit the ground running in 2021. It’s amazing what you can do when you have a couple extra weeks and a full crew on hand! Each year presents its own challenges. Last year I wrote about how the infamous (and unfortunately, still ongoing) pandemic disrupted the burn season. A record fire regime this year ensured the crew didn’t have to trek so much through unburned plots of land – that’ll really put your knees and hips to work! I also discussed the extremely wet spring of 2020. In a reversal of fortune, we ended up working during a drought year for 2021. Creek levels in late May were as low as they should’ve been in August, and most storms conveniently split to the north or south (often both) before they could supply Nachusa with some much-needed water. This drought meant the crew faced a mixed bag of effects: a lower invasive plant population and some seemingly confused natives. These “confused” natives often seemed to bloom and go to seed earlier than expected from previous years. New England asters started blooming at the very end of June! As we face the transition to fall, the focus of the crew has been mainly on seed collecting, as weed killing season drew to a close. We swept certain units no less than four times this season for birdsfoot trefoil, tore sweet clover out of the ground on remnant knobs, plucked king devil heads before they could go to seed, and even patrolled the roadside ditches, spraying yellow iris and scything parsnip. The crew feels incredibly lucky to have the new Morton building to process seed. Because of this, we’ve been able to collect and then subsequently mill record amounts of seed, blowing our 2020 numbers out of the water. As of this writing, we currently have milled over 250 pounds of seed from over 40 species. We’ve been able to collect some seeds we missed last year, such as the seed pods of blue flag iris, which explode and shower seed everywhere in the vicinity when ready. We’ve seen all sorts of seed diversity: sticky catchfly seeds as small as a grain of sand, hairy beardtongue seeds that smell like roadkill, delicately fluffy dwarf dandelion seed, black-eyed Susan seed that digs into your skin like fiberglass. They’ve been harvested from every part of the preserve and in any sort of environment: golden Alexander from a classic mesic prairie, sedges that require a good pair of muck boots to collect, and fameflower from the sandy, desert-esque remnant knobs of Nachusa. As the fall season kicks into gear, the crew will continue collecting even more species from all across Nachusa in preparation for future restoration projects. The crew has worked hard this season in all sorts of conditions. We can attest to some bone-rattling days in May where we wore two layers under our rain jackets. And we’ve also labored through unusually hot June and August days with heat indexes topping 115 degrees Fahrenheit. We’ve killed sweet clover during rainstorms and been blasted with 40 mph gusts as we picked seeds. At times, the restoration technician position can be physically demanding and exhausting; hauling a two gallon herbicide pack for eight hours on the prairie is no joke! But time and time again it has proven incredibly worth it. We’ve seen the 2020 planting come to life this year, and already some of the seeds we collected last year have sprouted up: black-eyed Susan, white wild indigo, partridge pea. It has proven especially worth it through our wildlife encounters. A mink on her morning pond patrol on a cloudy day. Rescuing a cliff swallow with twine wrapped around its toes. Listening to sandhill cranes uttering their melodious primeval cries. Scaring up more frogs in a few minutes than you could count on your hands and toes. We even found an endangered Blanding’s turtle whose radio tracker had died. And of course, we’ve had plenty of encounters with bison. As rut season begins, the roars of the bull bison almost sound akin to lions on the Serengeti. We’ve watched adult bulls size each other up, and yearling bulls jostle each other around in imitation of their elders. We’ve also seen a more tender side to the bison, as one crew member, Zach, was lucky enough to come upon a cow that had just given birth in late June. The calf couldn’t even stand up yet! All in all, it’s been an incredibly successful summer at Nachusa that has proven worth the hard work. Nachusa is truly a place like no other, and we all feel lucky to be a part of it. Meet the Crew

By Peter Guiden, PhD Post-Doctoral Fellow, Northern Illinois University An ecosystem is a complex, wonderful thing. It represents many species of plants, animals, and micro-organisms interacting with each other and the air, soil, and water. It is greater than the sum of its parts. And in restoration ecology, a central goal is to put degraded ecosystems back together. However, doing so is often a challenging process—that same complexity that makes an ecosystem beautiful can also make it difficult to manage. A logical starting point is to restore the native plant community. Plants play so many important roles in an ecosystem: they provide habitat and food for animals, they exchange nutrients with microorganisms, help develop soil, and link aboveground and belowground worlds. Every plant species plays a different role in the environment, so land managers often aim to restore as many native plant species as possible, leading to high biodiversity. At Nachusa, prescribed fire and bison reintroduction are used to meet this goal, knocking back the most competitive plant species and allowing many species to coexist. Hopefully, these diverse plant communities support many diverse animal species…right? It turns out that this question isn’t often asked. It’s difficult to answer, because scientists often specialize on one group of organisms, and individually lack the tools to measure how the ecosystem as a whole responds to management. Answering this question requires assembling an Avengers-style team of researchers, who can complement each other’s interests and expertise, at the same place and time. Luckily, the Nachusa community provided an opportunity for this to happen. Through collaboration between Nachusa, Dr. Holly Jones’ Evidence-based Restoration Lab at Northern Illinois University, Dr. Nick Barber’s Community Ecology & Restoration Lab at San Diego State University, and Dr. Rich King’s lab at Northern Illinois University, we could start to look at links between plants and animals. Each of these groups brings a unique skill set to the table. Dr. Jones and her students study plants and small mammals such as wild mice and voles. Dr. Barber and his students study plants, ground beetles, and dung beetles. Dr. King and his students study larger wildlife, such as snakes. Each of these groups has collected data on these animal communities over the past decade at Nachusa, including how many species occur in these study sites, and in what abundance. This gave us an opportunity to combine our data, and ask some broad, general questions about how restoration works. Here’s a link to the study we did, if you’re interested in the technical details. We wanted to know whether the areas with the most plant biodiversity also had the most animal biodiversity, or if something else explained patterns in animal communities. If plant and animal biodiversity were linked, that would suggest that restoring diverse plant communities may lead to recovery across the ecosystem. However, if the link between plant and animal biodiversity isn’t strong, other management strategies may be needed to boost native animal species. We found that in general, the best explanation of animal biodiversity had little to do with plant biodiversity. For example, small mammal communities were most diverse in areas that hadn’t been burned for a few years, because species like voles make their habitat in thatch (dead plant litter). Similarly, snake communities were most diverse in older restorations, because certain species take a relatively long time to colonize new habitats. This isn’t to say that plant biodiversity is unimportant for animals: there were many cases where plant and animal biodiversity were linked. Small mammal communities were more diverse in habitats with a rich mixture of forbs and grasses, and the most diverse ground beetle communities were found in areas with many plant species. But on average, the effects of management on animal biodiversity were six times stronger than the effects of plant biodiversity. Why didn’t we find a strong link between plant and animal biodiversity at Nachusa? One potential explanation is our choice of study species. Snakes and beetles are carnivorous, while small mammals are opportunistic omnivores, eating both plants and animals. Perhaps animals that are strict herbivores (especially insects with very particular diets) would have been more responsive to plant diversity. But for our animals, the age or structure of the plant community seemed to be more important than the number of plant species present. It’s also important to point out that maximizing animal biodiversity may not be the most important goal in a restoration project. Protecting rare species (like the rusty patch bumblebee) or species that play an especially important role in the ecosystem (like large dung beetles that eliminate large volumes of bison dung) may take center stage. In cases where restoring animal biodiversity is important, however, it may be necessary to consider how land management affects both plants and animals. One key take-home message of this study is that restoration really works. Through the hard work of land managers, volunteers, and scientists, it is possible to recreate diverse plant and animal communities in a very agricultural landscape. While we are constantly trying to learn more about how exactly these species respond to restoration, it is important to reflect on these successes. Ecosystems continue to be mysterious in many ways, but understanding a little bit more about them may help preserve their majesty and diversity for the future. Pete Guiden's ongoing research on restoration ecology is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

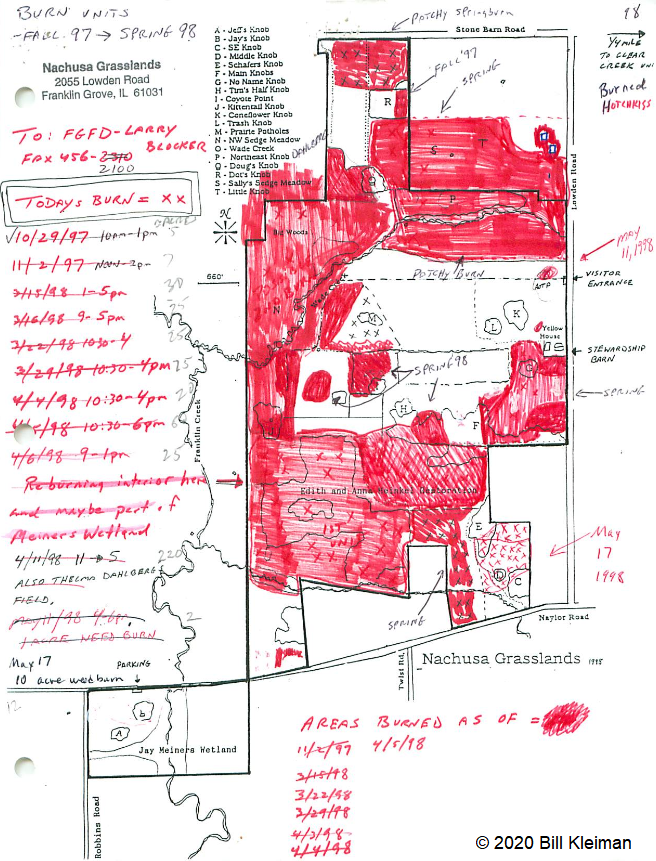

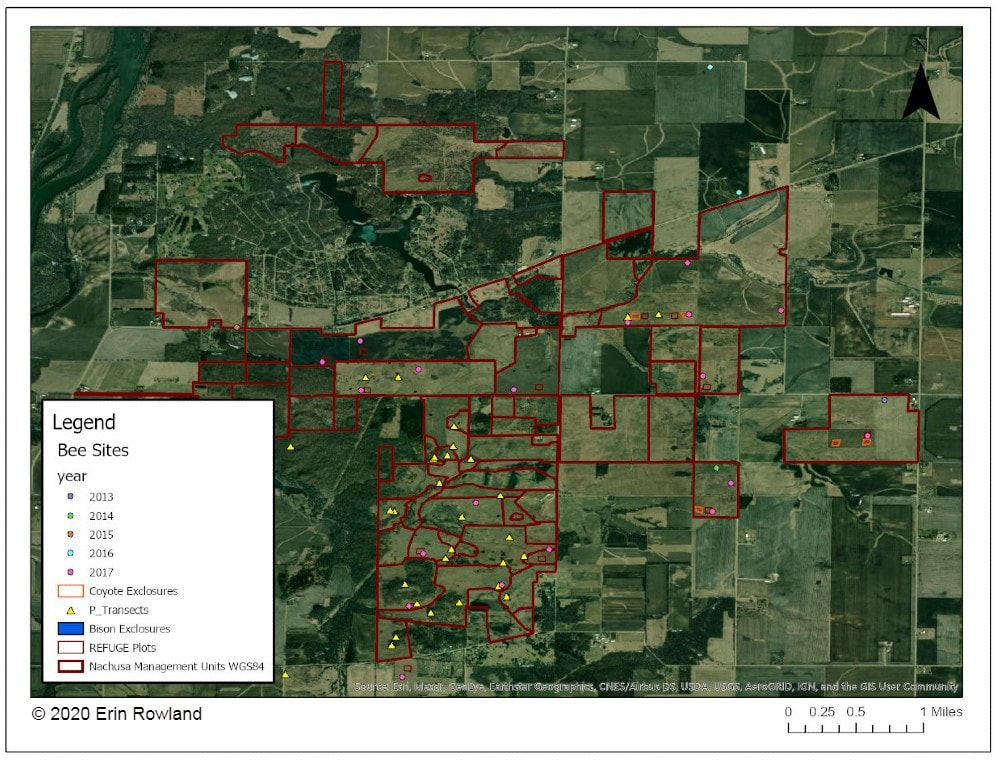

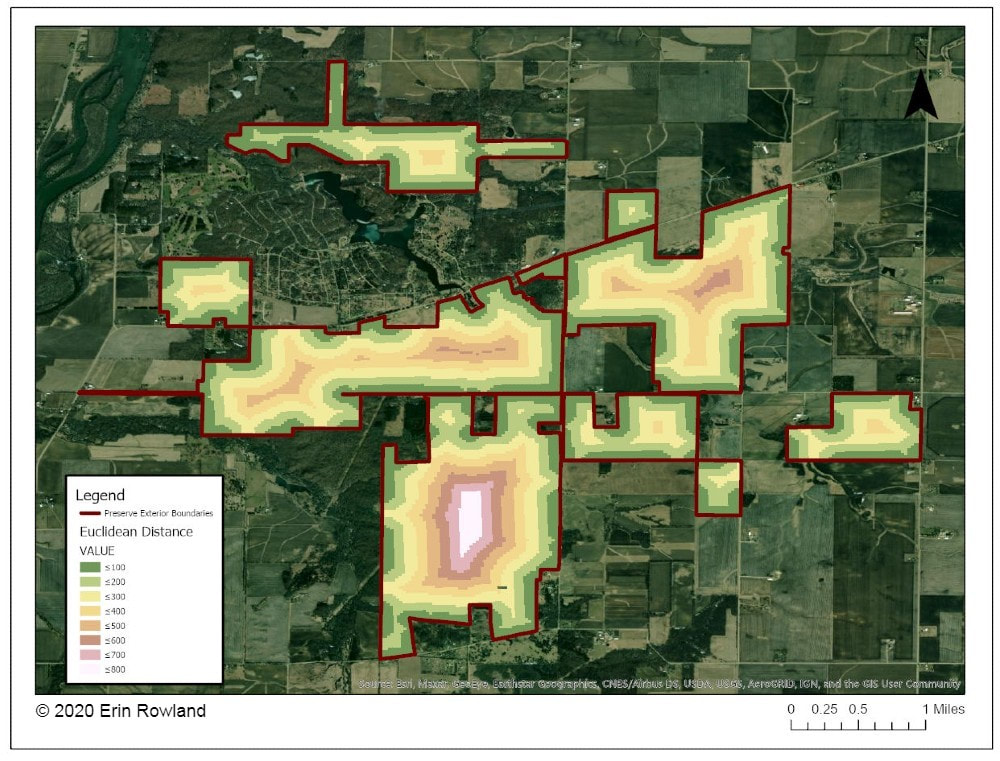

By Erin Rowland Summer Science Extern  Picturesque restorations like this are made possible by the work of volunteers and stewards on the ground. Science provides a new lens to better understand the impacts of this work. When I think of prairie restoration, I tend to think of the hands-on. I picture crews of volunteers collecting buckets of seed, or the summer crew fanned out in a line spraying weeds. Even the science done at Nachusa tends to conjure images of researchers trekking through the tallgrass after Blanding’s turtles, rodents, or butterflies. When I pictured my summer as Nachusa’s summer science extern, these were the images that filled my head. I couldn’t wait to spend my weeks under the sun trapping small mammals and surveying plant diversity. Meanwhile, the universe had other plans. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, research looked a little different this year. Many field scientists were able to conduct safe and socially distant work, while some researchers had to cancel their field seasons altogether. I was one of the unlucky ones. Instead of a summer in the field, I spent the summer at a computer. The funny thing is, this turn of events helped me to see the big picture. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a broad category of science that combines geography with other disciplines to create smart maps and analyze data throughout space and time. It’s a booming field, and it touches every aspect of our lives, whether we see it or not. GIS is used in everything from urban planning to public health to ecology. It allows us to ask and answer really interesting questions such as how the arrangement of land patches and proximity to different types of cover impact everything else on the preserve. This summer, I spent my time looking at the preserve from above in aerial imagery, trying to understand how all the pieces fit together. I spent a lot of my time converting old images of prescribed burn locations into a digital format, a process that feels a lot like a small child playing connect-the-dots. Tedious as it may be, this labor of love will help us see patterns through time in a new way. We can now easily ask how frequently certain areas of the preserve are burned and what that might mean for the plants and animals who live there.  Historically, records of prescribed burns were hand-drawn and not very precise. Our new digital fire maps are uniform and standardized, which will improve our ability to use the information. The second aspect of my work this summer was a bit more practical. Collaboration is one of the most valuable components of research at Nachusa Grasslands, and it’s part of what makes me so excited about working there. There’s such great diversity in the projects at Nachusa, as you can clearly see from the spectrum of projects funded by the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands science grants. One of my goals this summer was to compile a map of all the long-term research sites on the preserve, as well as to describe the types of data collected on these plots. By making information about data more broadly accessible, we can support better science that can benefit Nachusa and other prairie restoration sites. Researchers are better able to collaborate if they know what data exists and to whom to talk about it.  A map of long-term research sites at Nachusa will help researchers to more effectively collaborate and establish new projects more easily. The third part of my work this summer was beginning to understand the impact of human-made boundaries on a natural system. Plants and animals don’t care at all about the arbitrary places we draw our lines on a landscape. A piece of habitat is all the same to them, regardless of who owns it. This means that we have to be aware of the places where we create borders and boundaries and understand the impacts that they may have. A simple mowed path for a stewardship vehicle may seem minor to us, but might represent an insurmountable obstacle to a vole. One of the most exciting revelations of my work this summer is a success story in the tallgrass. I conducted analysis to understand how insulated different areas of the preserve are from the surrounding landscape. I created a heatmap to illustrate distance from the edge of the preserve, an attempt to classify land by how far it is from the proverbial “edge.” The results showed that the best-insulated area of the preserve is part of the original purchase that established Nachusa Grasslands. Not only was a beautiful portion of remnant prairie preserved, but the land around it was converted to create a pure prairie landscape with a buffer of protection from the surrounding agriculture and development.  This map helps us to understand how close various areas of the preserve are to non-prairie edge. We can see which areas are the most insulated from external impacts. Management happens at a variety of scales. Many decisions are made at the smallest scale: an invasive species can be removed from a part of a unit, and seeds can be collected from a rich patch of big bluestem to be planted next year. What’s harder to consider is how these seemingly small decisions work in tandem to create larger-scale impacts. The preserve looks different from above than it does on the ground. The challenge for managers is to be able to simultaneously see the prairie and the plants, as well as the forest and the trees. To meet the needs of a prairie restoration, one has to imagine the view of a turtle or a ground squirrel, in order to imagine a patch of grass as your whole world. At the same time, one must consider the big picture. Making decisions on the small-scale for the sake of specific animals or desirable plants can negatively impact the overall health of a system. What excites me the most as a researcher at Nachusa is the opportunity to do science that helps us make better decisions in restoration. By taking a step back out of the grass this summer, I had the chance to look at the preserve from a different perspective. I gained a new appreciation for the complexity of a prairie restoration project and the multi-faceted decision-making with which land managers are tasked. Now I look forward to taking my maps and figures and using them to ask more questions about how our work changes the landscape and how the landscape changes our work. Erin Rowland's ongoing research on small mammals and landscape ecology is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. To get involved withe the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. If you are interested in learning more about Erin's small mammal work, check out the recent blog by Jessica Fliginger or contact Erin to learn about opportunities to volunteer!

By Mary Meier Nachusa Grasslands volunteer Each May, Nachusa Grasslands’ staff and stewards usually dread the appearance of one of our major weed adversaries, reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea — RCG). This year, however, we may welcome the opportunity to attack the invaders, if and when we are released from our “stay at home” restrictions. The prospect of heading out into the field laden with herbicide backpacks is very appealing right now. What is reed canary grass? RCG is a coarse, cool-season perennial grass with erect hairless stems that grow from 2 to 6 feet tall. Densely clustered single flowers at the top of each plant change from green to purple to tan in late spring. Shiny dark brown seeds form during the summer months and shatter easily. Reproduction takes place both by seed dispersal and underground rhizomatous roots that create a thick, impenetrable mat just under the soil. Seeds can float down waterways and also spread via animals, humans, or machines. For example, Nachusa’s bison and deer populations may brush up against the plants and then carry the seeds in their fur. Where does reed canary grass grow? The plants thrive in moist areas, including marshes, swamps, prairies, meadows, fens, stream banks, and swales. It is especially abundant in disturbed wetlands, but can also appear in high quality native habitat. How did reed canary grass arrive in northern Illinois? Since the 1800s, agronomists have encouraged planting RCG for forage and erosion control. Some states prohibit selling the seeds, but Illinois does not. A native species actually exists, but it is almost impossible to distinguish from the more aggressive Eurasian variety. At Nachusa Grasslands we strive to eradicate all occurrences of RCG in order to diminish its ecological threats. Why does reed canary grass cause problems in our natural areas? RCG forms large monocultures, crowding out native species and building up a tremendous seed bank that germinates year after year. The thick thatch that forms from rhizomes and collapsed stems is especially problematic, as it prevents more desirable seeds from germinating. RCG, therefore, reduces native plant and insect diversity, while providing little shelter or food for wildlife. How do we manage reed canary grass at Nachusa Grasslands? Spraying grass herbicide is our main approach. The staff and stewards treat RCG with Intensity, a post-emergence grass herbicide (1% clethodim). Even though clethodim does not kill the plants’ roots, it helps set back the grasses and allows sedges and forbs to move in. Around waterways and high-quality natural areas, the crew uses the same formula with extra caution to reduce overspraying. What are some other reed canary grass control methods? Research and experience show that burning and mowing can actually stimulate regrowth of RCG but may also be useful in removing thatch prior to overseeding. Digging up rhizomes is labor-intensive and disturbs the soil, so other weeds may then invade the site. In small patches, cutting off the seed heads and disposing them off-site can be effective when combined with herbicide application. Covering with shade cloths is another option for large infestations. As with all weed management projects, best practices depend on overall goals and objectives, the size, distribution, and location of RCG infestations, willingness to use herbicides, and available human and equipment resources. In addition, every method requires follow-up monitoring, treatment, and establishing native species as we strive to extirpate this very challenging invasive species. Mary Meier has been a dedicated volunteer at Nachusa since 2002. She is currently an officer for Friends of Nachusa Grasslands, an Autumn on the Prairie festival organizer, and a member of the social media team. Along with her husband Al, she stewards the Dot and Doug Wade Prairie Unit, which is about half restoration and half remnant.

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry Spring Summer Autumn Winter

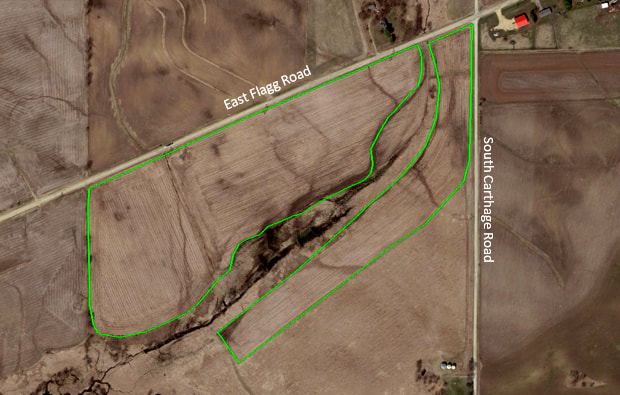

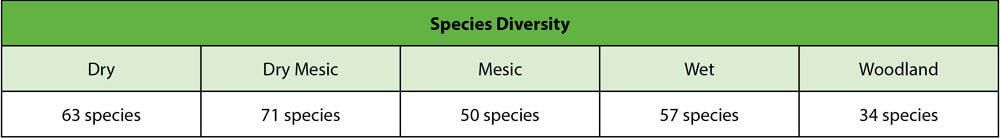

By Riley Nylin, Restoration Technician On November 18th, 2019 Riley Nylin, Tyler Pellegrini, and Amanda Contreras completed the 2019 crew planting on the corner of East Flagg Road and South Carthage Road. This 63-acre planting finishes off the Clear Creek Knolls management unit. Over the course of the season, our crew hand-picked 2,930 pounds of seed. Because of the extremely wet conditions of the picking season, we were forced to focus heavily on diversity instead of attempting to collect large amounts of seed. This led us to breaking only one seed collection record. We collected 29 pounds of pussytoes (Antennaria plantaginifolia) when the past record was only 14 pounds! Several different planting mixes were made, but not all of them were used on this site. The handpicked mixes are broken up into five categories: Dry, Dry Mesic, Mesic, Wet, and Woodland. The Wet and Woodland seed mixes were saved for other plantings/over-seeding areas. Within each mix, the crew focused heavily on species diversity. Table 1 displays the total number of species per mix. Once the seed was collected, separated, and mixed, the crew took to the field to plant! By planting 184 species at 50 lbs per acre, they planted a total of 85 acres of new prairie as well as over-seeding a few portions of past plantings. While 63 of the acres were planted at the Flagg and Carthage planting, the other 22 acres were planted at Franklin Creek Natural Area (FCNA). The FCNA planting was in partnership with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

By Charles Larry, with a thank you to Bill Kleiman for his help. Fire! The very word can conjure up images of terror or comfort. Forest fire, wildfire, or house fire evoke terror, while campfire, hearth fire, and cooking fire suggest comfort. Fire for a prairie or savanna means renewal. Fire is a necessary element in the way these ecosystems evolved. The native peoples of the prairies were using frequent low intensity landscape fires to encourage habitats that fit their needs for hunting, food, and medicine. The natural areas we now manage are dependent on those fires continuing. Fire kills the above ground portions of small trees and shrubs, sparing the oaks and hickories, which have adapted to fire with thick bark and the ability to re-sprout as needed. After a prescribed burn, the landscape looks bleak, seemingly devoid of life. But this is an illusion. Fire sets back woody plants, encourages wildflowers and grasses, and cycles nutrients. In just a few weeks vegetation begins to sprout anew. Plants such as wild lupine, foxglove, and ferns flourish after a prescribed burn. By summer, everything is in full bloom. Wildlife, such as deer, coyotes, foxes, rabbits, squirrels, opossums, raccoons, and birds, such as wild turkeys, red-headed woodpeckers, chickadees, goldfinches, indigo buntings, not to mention the myriad insects, all benefit from the lush environment. In this photo we see some old standing oaks that died from oak wilt or some other oak disease. Autumn is seed time and root time, returning again to underground. Dragonflies mass, preparing for migration. Migratory birds, such as northern flicker, indigo bunting, and summer and scarlet tanagers also gather in flocks to begin their migrations south. Tree frogs cease singing and bury themselves under logs, rocks, or leaf litter to hibernate the winter. The air becomes cooler. Frost happens with more frequency, foretelling the coming of winter. Winter is quiet and still but by no means vacant of life and activity. Deer roam about, eating dry grasses or other plants coming up through the snow, as well as twigs and the bark of trees. They also eat acorns or hickory nuts that have not been stored away by the squirrels. Coyotes and foxes prowl for voles or mice under the snow. Because the land is blanketed with snow, it protects the seeds that have been dispersed. When the snow melts in spring, it will help to plant and nourish those seeds. Thus the cycle begins again. This week's blog was written by Charles Larry, a volunteer and photographer at Nachusa. To see more of his images, visit his photography website.

“Budding Ecologists” — Nachusa’s Role in Mentoring the Next Generation of Natural Areas Managers9/15/2019 By Cody Considine

In her new role she will lead the crew for the remainder of this field season, which includes harvesting a couple more thousand pounds of seed from 150 species to plant 50+ acres this fall. In addition to the fall planting and prescribed fire season, she will also be interwoven into the bison roundup, helping with various tasks. This winter she will operate chainsaws and large equipment, removing brush in our oak woodlands. Next spring she will work to become qualified as a line boss position on prescribed fire. By the end of her residency (December 2020), Amanda will have the skillsets, confidence, and humility to be a natural areas manager.

Bill and I, along with Elizabeth and Dee, would agree that one of the most gratifying experiences in managing natural areas is helping grow the next generation of natural areas managers. We are immensely grateful for all of our young professionals who choose to start their careers at Nachusa. Please give them a shout out next time you come for a visit. Cody Considine is the Deputy Director at The Nature Conservancy’s Nachusa Grasslands. |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed