|

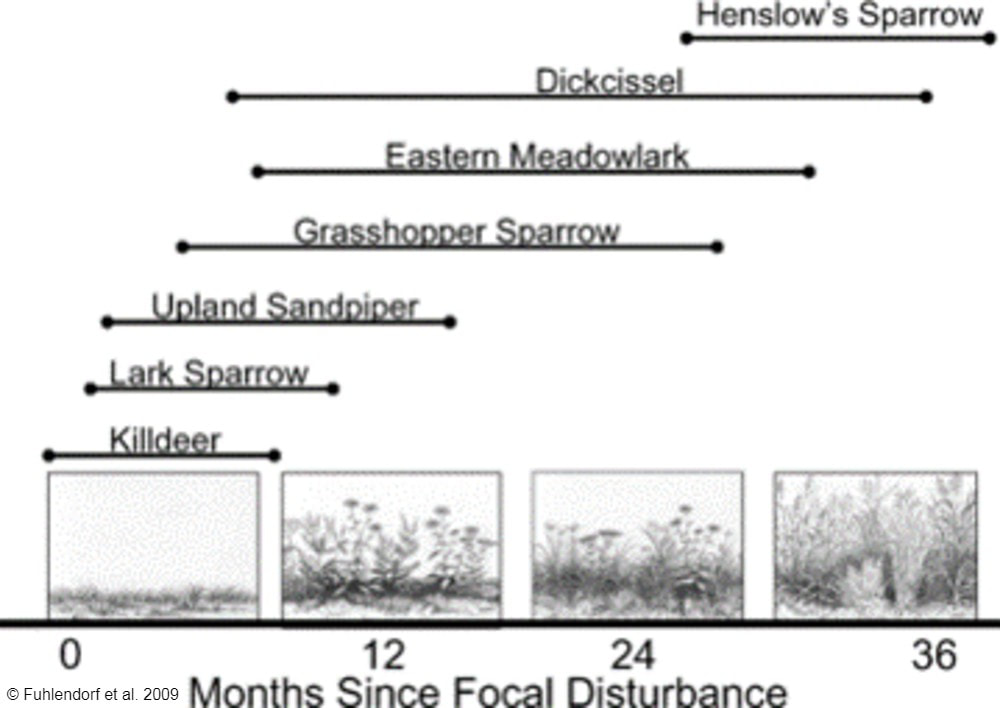

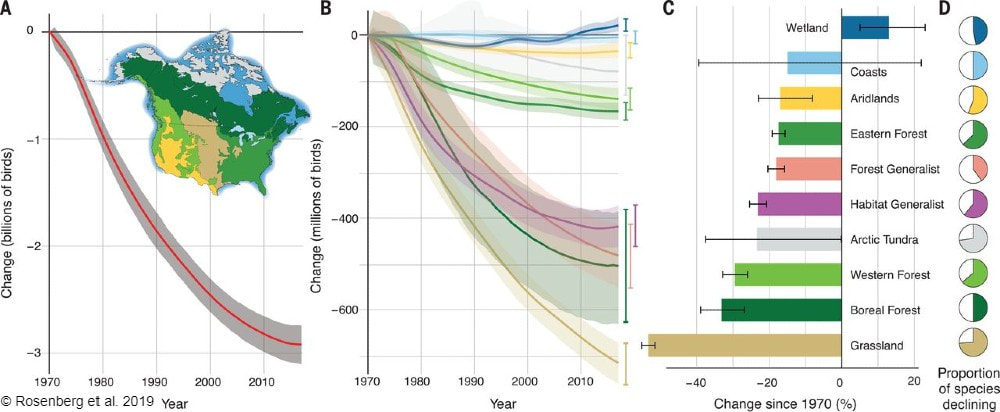

By Antonio Del Valle MS Student  Sunrises over the tallgrass praire were a wondrous daily event to behold while surveying at Nachusa Grasslands. This summer, as part of my graduate research project at Northern Illinois University, I had the opportunity of studying some of the many bird species that call Nachusa Grasslands home. Luckily, surveying birds is an activity that you can do by yourself, which was a key factor in being able to safely conduct my research project in the midst of a global pandemic. The focus of my research is to determine how birds that breed on the prairie are impacted by some of the large scale disturbances on the prairie landscape—mainly bison herbivory and prescribed fire. Different bird species prefer different types of prairie. Species such as killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and upland sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) prefer shorter prairies that, at Nachusa, are maintained through the eating of plants by bison and frequent prescribed fires. In contrast, species such as Henslow’s sparrow (Centronyx henslowii) and sedge wren (Cistothorus platensis) prefer dense, tall prairies that are maintained through infrequent disturbances.  A figure describing the relationship between different grassland bird species presence and months since a disturbance event has occurred on the prairie. Grassland birds are a suite of species that specialize in using prairie habitat as their preferred place to breed and raise young. These species are of particular interest to me because grassland birds have experienced drastic population declines. A recent paper published in Science shows just how serious this decline has been.  Bird populations in North America have declined by three billion individuals since 1970. Grassland birds in particular have declined more than any other group of birds. But it is not all doom and gloom for these grassland birds. Thanks to the hard work put into the restoration, management, and conservation of the tallgrass prairie habitat at Nachusa Grasslands, there are bountiful places for these types of birds to breed during the summer. My research aims to help us understand more about these declining species. Preserves such as Nachusa Grasslands give me an opportunity to observe them in areas where they are still relatively prevalent.  High quality prairie restorations take a lot of hard work but provide great habitat for many declining and rare plants and animals. A typical morning of surveying birds starts out by waking up well before sunrise. I set my schedule to arrive to Nachusa around 5:30 AM in order to start surveying during peak bird activity. Coming prepared with coffee and waterproof clothes were key factors in staying awake and dry while traversing the dew-soaked prairie. Upon arriving to a survey point at the preserve, I begin surveying birds via sight with my binoculars, as well as by sound. I record all of the birds I see and hear into my field notepad for five minutes. While surveying, I record the number of individuals of each species, estimate their distance from me, and record any breeding behaviors that are displayed. Surveying in this systematic fashion allows me to look at the data later and compare what birds were seen in what areas, how many were present, and whether I can confirm that they were breeding (according to eBird’s breeding bird behavior codes). Additionally, this format allows me to compare my data to other data sets across different years and potentially different preserves/sites.  The depth of the thatch layer covering the ground is measured by using a ruler. This layer of dead plant material is important for certain species that require cover. In addition to surveying birds, I also survey vegetation and bison density through dung counts. Vegetation surveys involve measuring vegetation height, thickness of thatch layer, and percent cover of plant species. These measurements give me quantitative values to describe the vegetation structure within different areas of the preserve. Bison density is calculated through systematically counting units of dung at my survey locations. Looking at bison density in different areas of the preserve can help show where bison are spending most of their time (and eating more plants). One of my favorite birds to observe this summer was the Henslow’s sparrow. This secretive sparrow is rarely seen on the prairie, as it spends most of its summer down low in the grasses and only pops up once in a while when singing or flying. The Henslow’s sparrow song is unique as well. Cornell University’s All About Birds online field guide describes it as the simplest and shortest song of any North American bird, and to me it sounds like a faint hiccup. These sparrows have a greenish wash on their face and fine streaks on their flanks, which help to distinguish them visually from other sparrow species if you have the pleasure of catching a glimpse of them. They, along with many of the other grassland breeding birds, are now on their way back to their overwintering grounds in Central and South America. The prairies will be noticeably quieter until they begin to return in the spring again. I’m looking forward to analyzing the data collected this summer and preparing for next year’s field season over the next few months. I hope that my research can help provide knowledge to aid in the continued conservation of these grassland bird species. Nachusa Grasslands is a wonderful place to observe these birds and many other plants and animals in their native habitat. Citations & Resources: Fuhlendorf, S.D., et al. (2009). Pyric herbivory: Rewilding landscapes through the recoupling of fire and grazing. Conservation Biology 23:588–598. Rosenberg, K.V., et al. (2019). Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 366(6461):120-124. Tony’s ongoing graduate research is supported by the following sources:

0 Comments

By Chandler Dolan Bumble Bee Technician Introduction The scene: It’s a classically humid, July afternoon. A gaze across the prairie shows patches of yellows and pinks, suggesting the presence of yellow coneflower and wild bergamot. As the heat intensifies, the birds and bison seem to slow. You stand quietly, intently listening to the sounds the grassland offers. Suddenly, a loud buzz tears through the patterns of bird melodies and katydid song. A familiar yellow and black face emerges from under a canopy of partridge pea: a bumble bee. Bumble bees are familiar insects. The shaggy combination of yellow and black (and sometimes orange) hairs with a plump, round build makes these insects nearly unmistakable. Their role of pollinating beautiful wildflowers and food plants alike is an important ecosystem service they provide us, free of charge. Their friendly buzz and frantic foraging suggest a healthy ecological system. Unfortunately, bumble bees face an uncertain future. Through habitat loss, pesticide use, and disease, many bumble species have experienced significant decline and are becoming increasingly rare. Thankfully, Nachusa gives refuge to three threatened species of bumble bees, including the critically endangered rusty-patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis). In 2017, Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar discovered the presence of the rare bumble bee at Nachusa in the form of a foraging worker. This was a great discovery, as the current distribution of the species is fairly unknown. To know this species was living at Nachusa was special and has given rise to new research opportunities and questions to be answered. With the new motivation of a federally endangered species in the Grasslands, new projects have begun! The 2020 season is the first season we have boots on the ground (in the form of me!) to monitor bumble bee abundance and diversity across all species of bumble bee at Nachusa. We start with simple questions: What species of bumble bees are here? How many of them are there? What flowers are they using? By answering these questions, we can start to form new questions and learn about the Grasslands. This season is all about exploration, experimentation, and just getting a sense of the bumble bees at Nachusa. Endangered Bumble Bees of Nachusa Grasslands As mentioned, the rusty-patched bumble bee is a federally recognized endangered species in the United States. In fact, it is the first bumble bee species to be listed on the United States Endangered Species Act. This characteristic bumble bee sports a unique “rusty patch” on its abdomen, which is one of its best identification traits, hence the name. The decline of this species is somewhat mysterious and very sudden. Prior to 1996, this species was abundant throughout much of the Midwest and Northeastern U.S. After 1996, the species tumbled into rapid decline and is now extremely rare in the Northeast. Most records of this species today are sporadically reported in the Midwest, but at very low rates. In the seven weeks I have been surveying, I have detected two rusty-patched bumble bee workers at Nachusa. To know this species is still present and not extinct is a great discovery alone. But understanding the way it uses the mosaic and where it chooses to nest is still up for question, and is difficult to answer with such sparse sightings. Our first sighting occurred very early in the field season. In fact, it was the fourth day of surveying! Seeing a single rusty-patched worker busily foraging on beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis) was a great way to start the season. Our second was about a month later on July 17th. Upon my arrival to a hill to do some quick exploration, the very first bee I spotted was the rare but distinct bumble bee methodically feeding on wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa). I held back tears of joy as I quickly netted the bee for proper identification. Nachusa also houses two other declining bumble bee species: the golden yellow bumble bee (Bombus fervidus) and the American bumble bee (Bombus pensylvanicus). Bombus fervidus has quickly become one of my favorite species, as its striking yellow abdomen and bold, black thorax band are impossible to miss. While these species are not recognized as endangered by the federal government, they have documented declines that warrant them a “vulnerable to extinction” assessment by the IUCN Redlist. I’m happy to report that these species are detected regularly and seem to like certain parts of the Grasslands. One day we hope to answer these questions: What parts of Nachusa are these vulnerable species found, and why? What makes one patch of habitat more suitable than another? Conclusion Bumble bees are interesting. Their familiarity provides a calming energy, as their small wings effortlessly lift their seemingly oversized bodies and loads of pollen to provide for the nest and its offspring. But despite how recognizable they may be, there is still much to learn about them. Simple things such as their habitat and favorite flowers are yet to be fully understood. A closer look into the world of bumble bees reveals a world of individual decision-making by our hairy friends that we are working hard to better understand. One of the first steps to conserving a species is to better our understanding of them. With the first long-term bumble bee surveying season at Nachusa underway, we hope to better understand our bumble bees and to one day provide them the best habitat we can. To lose a species is to lose a piece of a puzzle. Once gone, the picture will never be the same, with a hole no other piece can fill. *** UPDATE: On July 29th and 30th, two more rusty-patched bumble bees were observed at Nachusa! That makes a total of 4 observations this season! *** Dr. Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar's ongoing research on Nachusa's bumble bees is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. If you would like to play a part in helping the bees at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. Chandler Dolan graduated from the University of Northern Iowa in December of 2019. Throughout Chandler's career as a young biologist, they have been continually drawn to endangered species ranging from the rusty-patched bumble bee to neotropical parrots and migratory songbirds. As Chandler dives deeper into the world of bumble bees, they hope to pursue bumble bee conservation as a long-term goal for graduate school.

By Connor Ross Nachusa Restoration Technician It should go without saying that 2020 has been a pretty, let’s say, interesting and hectic year so far. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic delayed the start date for the 2020 crew to the beginning of June also disrupted the scheduled prescribed burns earlier in the year. A diminished burn season, with one of the wettest Mays on record, means that our native vegetation has grown thicker and that the invasives have started to strike with a vengeance. The 2020 crew thus faces some unique challenges, especially as we are a smaller bunch this year, but we have already covered lots of ground and are ambitiously weeding and seeding. Our main focus these last few weeks has mostly been on controlling invasives. Already, we have been showering king devil, sweet clover, and birdsfoot trefoil with herbicide. Oxeye daisy and the occasional alfalfa plant have been sprayed when convenient, but unfortunately, the late start to the season means that we have been unable to control red clover. Nonetheless, the four of us have traversed quite a bit of acreage; we managed to sweep a full 70 acres for sweet clover on June 5th! Seed collection is ongoing and will increase as the season progresses. Already we’ve collected pussytoes, lots of wood betony, and the lovely prairie smoke! We’ve also learned that an abundant harvest of dwarf dandelion seeds won’t even constitute a handful, prairie ragwort will make you sneeze, and that you need an abundant supply of pantyhose to collect Hill’s thistle seed. The 2020 crew looks forward to collecting as much as we can this summer and dealing with the unique properties of each seed, from bunches of spiderwort that’ll dye your hands blue to the aptly-named porcupine grass seeds that will stab you through your work gloves! Meet the Crew

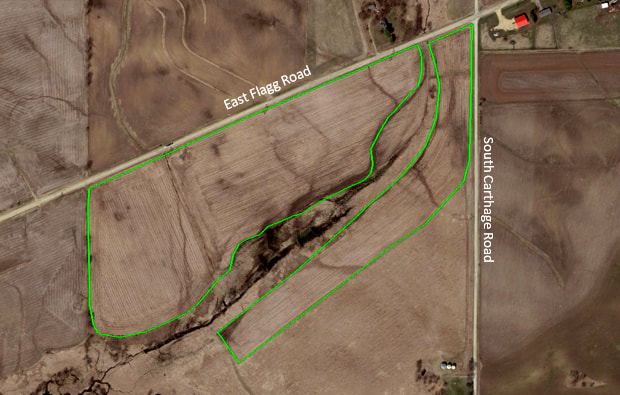

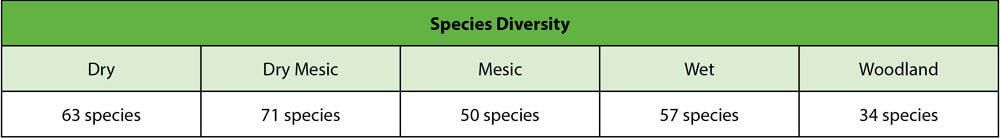

By Riley Nylin, Restoration Technician On November 18th, 2019 Riley Nylin, Tyler Pellegrini, and Amanda Contreras completed the 2019 crew planting on the corner of East Flagg Road and South Carthage Road. This 63-acre planting finishes off the Clear Creek Knolls management unit. Over the course of the season, our crew hand-picked 2,930 pounds of seed. Because of the extremely wet conditions of the picking season, we were forced to focus heavily on diversity instead of attempting to collect large amounts of seed. This led us to breaking only one seed collection record. We collected 29 pounds of pussytoes (Antennaria plantaginifolia) when the past record was only 14 pounds! Several different planting mixes were made, but not all of them were used on this site. The handpicked mixes are broken up into five categories: Dry, Dry Mesic, Mesic, Wet, and Woodland. The Wet and Woodland seed mixes were saved for other plantings/over-seeding areas. Within each mix, the crew focused heavily on species diversity. Table 1 displays the total number of species per mix. Once the seed was collected, separated, and mixed, the crew took to the field to plant! By planting 184 species at 50 lbs per acre, they planted a total of 85 acres of new prairie as well as over-seeding a few portions of past plantings. While 63 of the acres were planted at the Flagg and Carthage planting, the other 22 acres were planted at Franklin Creek Natural Area (FCNA). The FCNA planting was in partnership with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

By Mary Meier What do 400 hours of volunteer stewardship, $7,000 in donations, and 100 hours of social media posts have in common? They are all components of the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation’s Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program.

The Foundation encourages increased local support and participation in the care of habitat by providing grant funds as a match to local dollars raised and labor donated. Friends of Nachusa Grasslands has been approved for grants totaling $32,000 if we fulfill requirements under several categories:

Friends chose Nachusa’s Orland Prairie, a prairie remnant on the west end of the Big Jump Unit, for its habitat restoration project site. Volunteers have already begun attacking the 23-acre parcel that is heavily infested with the invasive shrub autumn olive. Non-native honeysuckle is also rampant in the area. Mike Carr, Orland Prairie volunteer steward, who has been working on the unit for several years, says, “I really enjoy brush clearing, especially the nasty stuff.” Both autumn olive and honeysuckle are some of the most tenacious foes that Nachusa’s volunteers battle. According to The Nature Conservancy, “Autumn olive is quickly becoming one of the most troublesome shrubs in central and eastern United States. High seed production, high germination rates and the sheer hardiness of the plant allow it to grow rapidly.” In addition, a University of Illinois extension website says, “Controlling bush honeysuckle is vital to the preservation of native ecosystems in Illinois. Bush honeysuckle currently poses one of the greatest threats to forest ecosystems in Illinois.” Saturday workday crews and individual volunteers are using herbicides to kill the woody brush invading Orland. Later this year and early next year, we will over-seed the area with native species collected during the harvest season, conduct prescribed burns, re-contour unsightly gravel pits, and remove non-native trees and large debris from fence rows at the site. Our long-term goal is to establish a diverse prairie planting on the 23-acre site, providing for long-term weed management and suppression of non-native shrubs and trees. Ongoing stewardship efforts, including volunteer labor, herbicide application, and controlled burns, will gradually help integrate the target area into the surrounding habitat.

How can you help Friends earn the stewardship grant? Volunteer for a Saturday brush clearing workday at Orland Prairie — the next one is on June 9. During the summer and fall, you can also help collect prairie seeds for Orland from the preserve. The Friends Social Media Team uses Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and our website to promote volunteer opportunities.

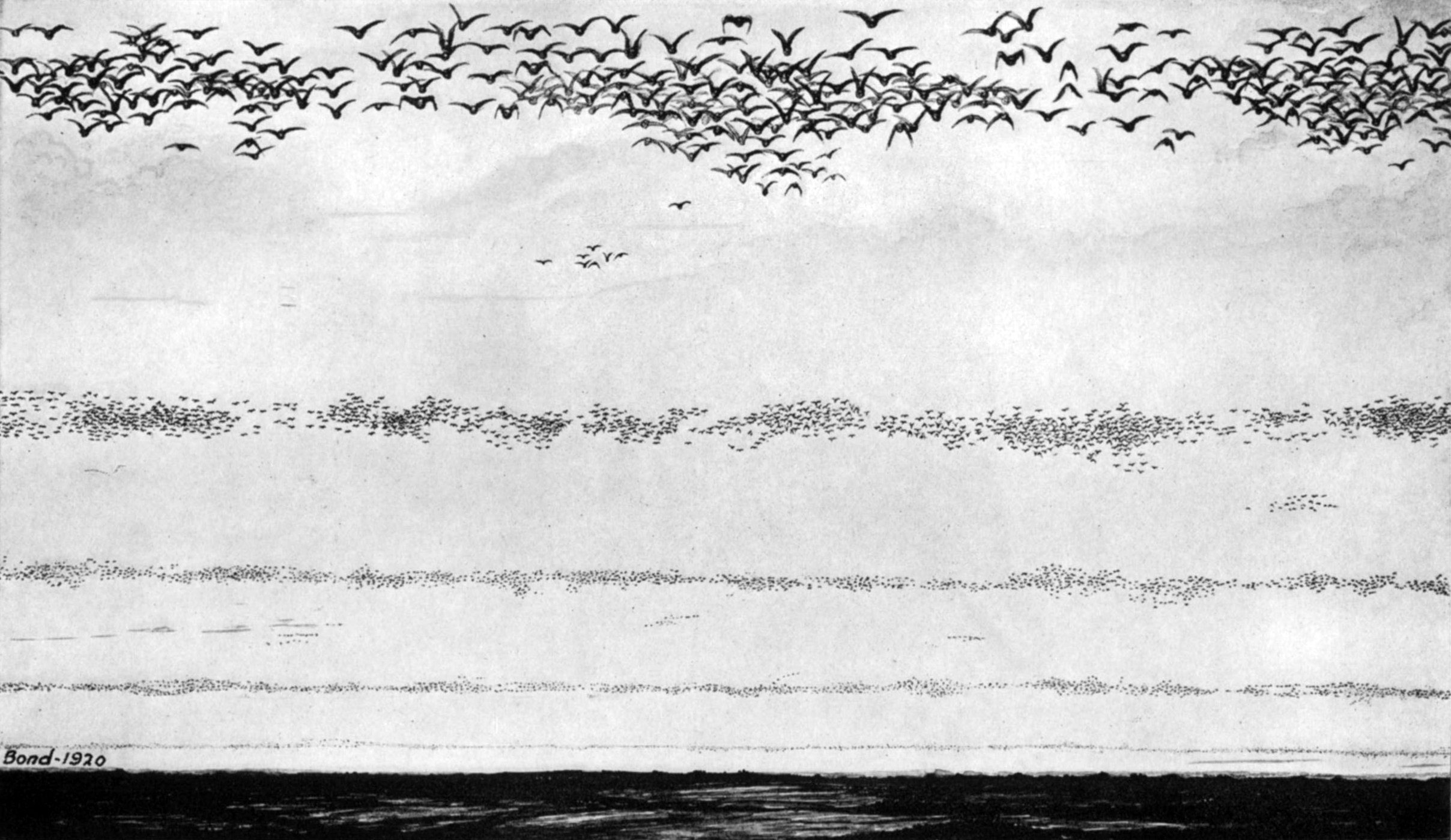

You can also follow Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation’s Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program on Facebook and Twitter to learn more about the Foundation. There was a time when seasonal migrations of passenger pigeons arrived with “a loud rushing roar, succeeded by instant blackness.” A black dense cloud of birds would darken the sky for hours, if not days, over the place we now call Nachusa. Passenger pigeon droppings fertilized the earth. The birds’ consumption of woodland seeds was an important mode of dispersal for many plants. While roosting and nesting the combined weight of their bodies was enough to break branches and topple whole trees, resulting in a thinning of the forest which allowed light to reach the ground. A flock of the now extinct birds visited Oregon, Illinois in 1843. Observer Margaret Fuller remarked, “Every afternoon [the pigeons] came sweeping across the lawn, positively in clouds, and with a swiftness and softness of winged motion, more beautiful than anything of the kind I ever knew. Had I been a musician, such as Mendelssohn, I felt that I could have improvised a music quite peculiar, from the sound they made, which should have indicated all the beauty over which their wings bore them.” It is hard to overemphasize just how numerous passenger pigeons were. The dramatic drop from the flocks of billions to zero in less then a human lifetime was a wake up call to the exploitation of birds and other wild animals. The disappearance of the passenger pigeon prompted legislators to enact laws protecting birds and game. Representative John Fletcher Lacey, on the floor of the House of Representatives on April 30, 1900, introduced what would become the first Federal bird-protection law.

Nachusa is the home of many plants, animals, birds and insects that were once common and are now rare. Walk one of the five trails at Nachusa and bear witness to rare species in revival. A few examples of rare species that call Nachusa home: I recently had the pleasure of experiencing a rare bird at Nachusa. I was at the Headquarters Barn after a day of adventure and when I heard the call I wondered, “What bird makes this wonderful sound?” It announced its name with each call: “Whip-poor-will, Whip-poor-will.” Once a common bird, whip-poor-wills, like all nightjars, are in steep decline. According to The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s “All About Birds,” night jars are hard to breed in captivity, and there are no excess populations from which to take birds for a reintroduction project. Scientists are not sure of the reasons whip-poor-wills are disappearing. Loss of open under-story forest is one possibility. At Nachusa clearing brush and returning fire to the woodlands begins to restore habitat. This habitat provides an abundance of insects, including moths, beetles, stone flies, and grasshoppers. These are favorite foods of whip-poor-wills; they hunt just after dusk and right before dawn, or on moon-bright nights they may hunt all night long. In one of those true mysteries of nature, whip-poor-wills seem to time egg laying so the chicks hatch ten days before a full moon, providing the parents extra time to gather food for fast growing chicks. When at Nachusa listen for the sounds of this rare bird. The passenger pigeon migrated into history before people realized the toll their activities were taking on wildlife. As awareness grew, people acted through government to protect native birds and animals. In time non-profit organizations such as The Nature Conservancy (TNC) bought lands of high biological diversity to preserve as many species as possible. TNC’s Nachusa Grasslands preserves and restores high-quality grassland, savanna, and woodland remnants for the future. Those high-quality remnants are the anchor areas to restore former agricultural areas back to nature. The Friends of Nachusa Grasslands aids this effort by supporting science research, to better understand the impacts of restoration efforts and how they might be improved. It’s too late for the passenger pigeon, but not the whip-poor-will and other species that will benefit for generations to come from the efforts at Nachusa. This week's blog was written by Paul Swanson, a volunteer at Nachusa. Sources

Prince, Jennifer. Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. New York: Basic Books, 1999. "Passenger Pigeons in Your State, Province or Territory." (2012). Retrieved from: http://passengerpigeon.org/states/Illinois.html. Greenberg, Joel. A Feathered River Across The Sky. New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2014. "Eastern Whip-poor-will." (2017) Retrieved from: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Eastern_Whip-poor-will/overview. |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed