|

By Susan Kleiman Nachusa Volunteer Shrubs and vines can sometimes be underappreciated, or worse, unknown. I will present a blog now and then on those species growing at Nachusa Grasslands. I am starting with five shrubs that we have good photos for, although we have identified at least 45 shrubs species and 20 vines (some woody and some herbaceous). By shrub I mean woody plants that attain less than 20 feet in height and often have multiple stems rising from the same roots. I will not include species that normally grow into trees, such as oaks (these and other trees can be shrub-like in form due to repeated fires causing them to re-sprout with multiple stems). I seek to understand the shrub component of Nachusa more fully. I do think from my reading and observation that many of the shrubs were historically present in our area in thickets or along waterways, not as single bushes dotting the prairie. I think we should carefully plant the seeds of shrubs in appropriate places. Some bird species, such as Bell’s vireo, yellow-breasted chat, willow and alder flycatchers, cedar waxwing, common yellowthroat, and indigo bunting, as well as others, particularly need shrub habitat. Shrubs are a major component of Nachusa’s grassland ecosystem in certain places. The Nature Conservancy calls our region the Prairie-Forest-Border Ecoregion. The State of Illinois calls our natural division the Rock River Hill Country-Oregon Section. Writing in the Geological Survey of Illinois in 1873, James Shaw said of Lee County, “The north-western part of the county, where Rock river cuts across the corner, is rough, hilly, and in places picturesque, especially in the vicinity of that stream. The hills and ravines in this locality are partially covered with dense underbrush and scattering timber.” In 1860 Dr. M. S. Bebb described the flora of Ogle County in a letter to a friend, which was also shared in a publication called Prairie Farmer. He says, “The rise at the border of the valley is usually covered with forest trees which have here found protection from the prairie fires, such as Quercus macrocarpa, Tilia Americana, &c with a variety of undershrubs and herbaceous plants, common everywhere in the woods of this latitude...” In the part about the groves he says, “Beneath we find an abundant growth of shrubs, principally Hazel (Corylus Americana) and Cornus paniculata*, the Hazel often extending out into the prairie for a mile or more, forming what is called a 'Hazel ruff'.” Mary Sackett wrote in her journal in May of 1842, “Sometimes our road lay across the prairie, sometimes through the thickets where the crabapples, choke cherries, strawberries and other fruits were in bloom, making the air very fragrant.” Some of our shrub species seem weedy and others difficult to grow, or even rare. This is likely due to the past disturbances such as plowing, over grazing, and over shading, or lack of disturbance by fire. * Cornus paniculata is now Cornus racemosa, gray dogwood. Ninebark Physocarpus opulifolius, Rose Family Rosaceae This is a gorgeous, widespread native shrub. I just saw some on the Olympic Peninsula. Its genus name Physocarpus is Greek, meaning “fruit like a pair of bellows.” The species name opulifolius is Latin, meaning “splendid foliage” or having the leaves of Viburnum opulus (referring to a European plant, Guelder rose). Luckily this species is hard to misidentify here at Nachusa Grasslands. Besides having good nectar for bees and butterflies, the large landing platform of the flower clusters is perfect for beetles, and the pollen is easily available to their chewing mouthparts. The clustering fruits have unique bladder coverings, and in fall the fruit and leaves can often be quite colorful. The common name of ninebark refers to the papery and shreddy bark of older branches. In open growing situations the shape of this shrub tends to rounded with weeping branches drooping to the ground. It is said it reaches a maximum height of ten feet, but I have not seen one taller than about seven feet here. At Nachusa we have a few ninebark here and there, often mixed with other shrub thickets and fence lines with such species as American plum and dogwood. It is said that it prefers stream edges, gravel bars, moist thickets, but it is also found in dry areas here. Many cultivars of this species have been developed by plant nurseries. Prairie Willow Salix humilis, Willow Family (Salicaceae) The genus Salix is Latin for willow, and humilis is also Latin, meaning low, humble, grounded, or from the humus (earth). I have not seen it taller than three feet here, and I can only think of five clumps outside of the one next to the Headquarters parking lot, so look out for this special bush, usually on dry remnant hills. Deer and rabbits will browse the twigs and leaves. The catkins and nectar are very important to a great many insects in the spring. Willow bark is the original aspirin, in use for at least 3500 years! Common Elderberry Sambucus canadensis, Moschatel Family (Adoxacea, formerly in Caprifolicaeae) Sambucus is Latin for elder-like, perhaps also derived from Greek sambuce, an ancient wind instrument, referring to the use of the stems to make whistles after removing the pith. Sometimes this shrub is called American elder. Elderwood in Europe was used to make a kind of harp called a sambuca. Canadensis refers to Canada, the country where this species finds its most northern distribution. This species extends all the way south to Bolivia. Elderberry forms colonies by root suckers and is most often found on our fence lines. The bark of the stems has distinctive, raised dots (lenticels) and leaf scars with connecting lines between the opposite compound leaves (not to be confused with ash species, Fraxinus). I have noticed that the cluster in my yard flowered most profusely the same year it had been burned, rather unlike many other shrubs we have, which can take several years post burn to flower. The flowers can be used to make a lemon-scented drink. But the berries are the best known part of the plant, used in wines, jams, jellies, and pie fillings. The flowers attract a small variety of insects. Leaves and twigs are browsed by deer, and the fruit is eaten by all kinds of birds and other animals. Unripe fruit, leaves, and stems are toxic to humans. Cooking the ripe fruit destroys the alkaloids. Smooth Sumac Rhus glabra, Cashew family (Anacardiaceae) This family of plants produces urushiol, an irritant, and includes poison ivy, mango, and cashews. Smooth sumac does not seem to irritate. Rhus is the classic Latin name for this genus, while glabra is Latin for smooth. This is Nachusa Grasslands’ only extant Rhus, as far as I know. We have, however, planted fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatic) in some areas. Smooth sumac is claimed to be the only native shrub found in each of the lower 48 states. Smooth sumac tends to grow in large clones that can sometimes shade out other species. Our fires often keep it shorter and sparse enough to allow prairie under the stems. In some places stewards have tried to reduce sumac stems through basal bark treatment. Individual shrubs are either male or female. The flowers, pollinated primarily by bees, also attract a number of beetles and bugs. It seems that the leaf beetle, Blepharida rhois, is the only insect that can eat the leaves which contain strong tannins, phytols, and compounds related to gallic acids. The beetle larva puts its concentrated feces on its back to deter predators. At Nachusa, smooth sumac is the last shrub to leaf out in the spring and one of the first to lose chlorophyll in the fall, usually turning a brilliant red. The bright red fruits have a lovely lemon taste and tartness. They can be eaten and used to make a refreshing drink, and in fact have been for thousands of years. Many animals eat the fruit as well, and various natural dyes have been made from all parts of the shrub for coloring cloth and plant fibers. Wafer Ash or Common Hop Tree Ptelea trifoliate, Citrus family (Rutaceae) Ptelea is Greek for elm, alluding to the winged fruits similar in appearance to elm seeds. Trifoliate is Latin referring to the three leaflets of each leaf. It is neither an ash nor a hop, although the strong odor of the plant is similar to, but not as nice as, the beer-making hops. The fruits were tried as a hop substitute to no lasting effect. The pale greenish-white flowers attract bees in the spring. The wind-carried seeds turn brown in the fall and persist into winter. Each wafer actually has two seeds, unlike the wafers of elms. This species, along with one other at Nachusa, prickly ash (wait for my next blog), are the only hosts on the preserve to the larva of the giant swallowtail butterfly, Papilio cresphontes. This shrub is quite common here, tending towards weediness, in my opinion, as it pops up all over the prairie. It is usually no more than eight feet tall with multi-stems. I have occasionally seen them here or off site as tree size, six to eight inches in diameter and 20-30 feet tall. This is in situations without frequent fire. Sources: Hyam, Roger and Richard Pankhurst. Plants and Their Names: A Concise Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press Inc, 1995. Kurz, Don. Shrubs and Woody Vines of Missouri. Jefferson City, MO: Conservation Commission of the State of Missouri, 1997. Petrides, George A. A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1986. White, John. Rock River Area Assessment, Volume 2. Springfield, IL: State of Illinois, 1996. Wilhelm, Gerould and Laura Rericha. Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis. Indianapolis: The Indiana Academy of Science, 2017. Useful website: https://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/trees/tree_index.htm If you would like to play a part in habitat restoration for native shrubs at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays, or give a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to support the ongoing stewardship at Nachusa.

4 Comments

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry Spring Summer Autumn Winter

Autumn has always been my favorite season. Oaks are my favorite trees. So, it seems fitting in "Oaktober" to write about oaks and oak woodlands At Nachusa Grasslands and other places in the Midwest, we are trying to restore the health of our oak woodlands. And really, our region is defined by the oaks. The Nature Conservancy calls our eco-region “The Prairie-Forest Border” between the grand prairie to the south and the mixed woodlands in neighboring states to the north. The area was historically maintained as prairie intermixed with oak savanna and woodlands by Native American nations. Natural plant and animal communities of the region were a direct result of Native Peoples’ use of fire on the land. Without fire, in “The Prairie-Forest Border,” the amount of rain we receive would have yielded dense forests. Many botanists have defined the various intergrades between savanna, open woodland, and closed woodland by the level of sunlight and density and species of trees. (See https://oaksavannas.org/) Today, much of our Illinois woodlands have become too shady to allow sun-loving oaks to grow. Shade is the enemy of oaks. Acorns in shade will not thrive after germination and the limbs of oaks will also die if shaded. How can we tell if the “woods” we are looking at was historically savanna or naturally shady? The presence of large, old oaks with limbs that stick straight out (or used to, but are dead now) indicate the area was likely savanna. An oak growing in full sun without other trees close by will grow limbs horizontally. Oaks that grow close together grow their limbs vertically to reach the sun. To give the oaks a fighting chance modern prairie restorers make use of controlled burns, as well as actual removal of invasive trees growing under and up into the limbs of the old sentinel oaks. We also remove the non-native bush honeysuckle (and other non-native shrubs) from the understory. Our region’s historic mixture of prairie interspersed with woodland types — from dry to wet, from open to somewhat shady — had an enormous species diversity of understory flowers, grasses, and native shrubs. If action is not taken by restorers, the result is a mud forest floor, impenetrable understory with honeysuckle bushes, and an overstory of dead oaks. Elms, maples, and other shade-loving fire intolerant trees move in to take the place of oaks and hickories. This combination of a solid thicket of invasive honeysuckle and loss of oaks gives hardly any habitat for animals. For example, deer and turkey dislike maple and elm, but they love acorns! Native oak-hickory savannas and woodlands in the region are disappearing along with bird species that depend on the open structure: red-headed woodpeckers, great crested flycatchers, and eastern bluebirds. Native wildflowers such as kitten tails, wild hyacinth, prairie lily, and starry campion along with grasses such as bottle brush rye, woodland brome, and long-awned wood grass will not grow in heavy shade. And there are the native shrubs: hazelnut, American plum, hawthorn, and Iowa crabapple! None of these tolerate shade either.

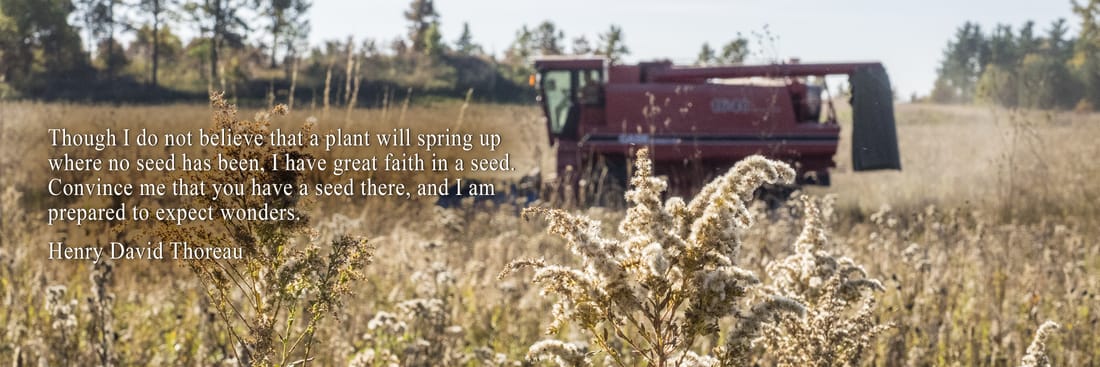

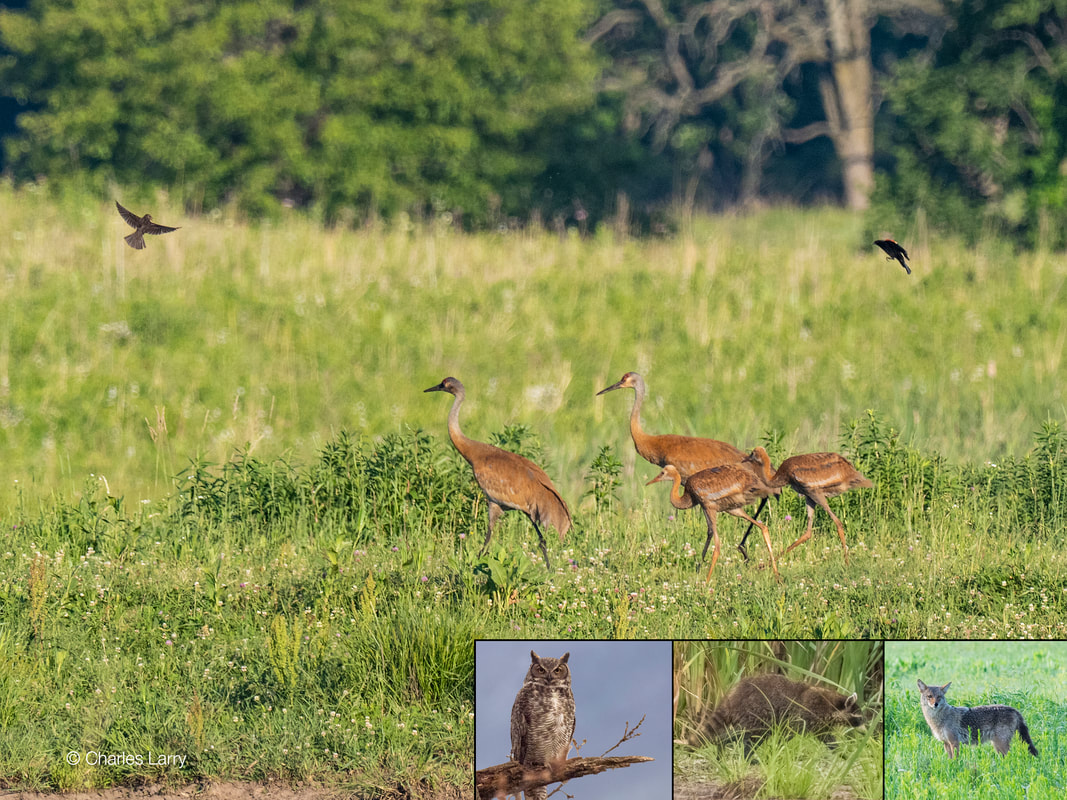

I encourage you to read up on oak woodlands, then take a hike. Explore the Stone Barn Savanna and see how we are doing. It’s a work in progress and sometimes messy, but we see the native oak savanna dependent plants and animals are thriving. Here are some great websites that discuss oak savannas: Pleasant Valley Conservancy—Oak Savannas Last of the Oak Savannas Survive in Minnesota What is an Oak Savanna? Written by Susan Kleiman, a Nachusa volunteer. Seeds! That essential element of prairie restoration, seeds are hand gathered and then planted by stewards, volunteers, and crew over hundreds of acres at Nachusa Grasslands each year. Gathering seeds by hand assures that only the right, ready, and wanted species are collected. But there is another method of seed harvesting and planting utilized at Nachusa: mechanized, with combine and broadcast seeders. With a combine, very large areas of seeds can be gathered in a very short time. In 2016, the Nachusa crew hand collected about 4000 lbs. of seed, while combining yielded about 20,000 lbs. Combining is not as precise a method as hand gathering and will retrieve the seeds of everything in its path, including weeds. This is minimized by carefully monitoring the path of the combine and either driving around an area of unwanted seeds or by disengaging the combine head. The photo above shows a field which yielded a variety of seeds: Big and Little Bluestem; Indian Grass; Smooth, Sky Blue, and Silky Asters; Old Field, Missouri, and Showy Goldenrod; Rough Blazing Star; Round–headed Bush Clover; and Pale Purple Coneflower, among others. The advantage of this method, in addition to large-scale collecting, is that it frees the crew to concentrate on rare, harder to collect seeds, such as from those plants that are too low to the ground to gather by combining. Combines can operate with different types of heads (front part of combine) for harvesting various grains and seeds. Nachusa's combine uses a rice-stripping head. The metal "fingers" (photo above) spin very fast, stripping seeds off each stem. This is much more efficient and collects less chaff compared to using a soybean head, which cuts and harvests the stems along with the seeds. The combine has also been further modified: the fans have been turned off and the top of the stripping head has been covered with a wire screen to minimize the loss of the fine, fluffy seeds. Because the special head brings in very little chaff, the seeds can be directly planted without going through the hammermill. After drying, the seed collected by combining is mostly given to conservation partners of Nachusa Grasslands, such as Byron Forest Preserve, Natural Land Institute, and Franklin Creek State Natural Area. Some of the seed is used to supplement the seed hand gathered by stewards and crew. Some of the seed is used to plant areas that were recently cleared of brush. This 103-acre field is much too large an area to plant by hand. The crew fills antique broadcast seeders with a mixture of the combine-gathered seed and hand-gathered seed. The broadcast seeders, attached to the back of trucks, are then driven over the field, again and again, spreading the seed. There are many factors that filter into a successful restoration. Weather, of course, is one factor. Often, after an initial planting, there are places where growth is sparse. Overseeding is done, sometimes over several years, to help increase growth and also to add more diverse plants. Diligent weeding is also done to eradicate unwanted and invasive species. New plantings are often burned on a yearly basis for a few years to help with weed control and encourage native species growth. Nachusa's staff and volunteers have gone through this process of collecting and planting prairies over 120 times within the past 30 years. After many years of care and hard work, a beautifully restored prairie may bloom. This blog was written by Charles Larry, volunteer and photographer at Nachusa. To see more of his images, see: charleslarryphotography.zenfolio.com

In the fall I look forward to the incredible display from the native prairie grasses. Up to this point, the grasses have remained rather unobtrusive, but in the fall they step out of the background to claim our attention. Although I enjoy them all, the little bluestem grass is definitely my favorite. Little bluestem can be found throughout the prairie, but right now this grass is very noticeable if you to look the hills. Many of Nachusa’s knobs and hills are blanketed in an orange–red, and that color is from the . . . little bluestem grass!! In addition, throughout the winter, the grass will retain this energetic color and stand out beautifully in the snow. As the autumn winds blow, the little bluestem grass undulates like waves in the ocean, as seen in the photo above in the upper left. It is mesmerizing to watch it ripple across a vast expanse. The view is from the top of Fameflower Knob in early fall (notice the leaves still on the trees). As a photographer, I love to use little bluestem as a backdrop for the goldenrods and asters that bloom in the fall. Then, as the season progresses, the grass creates a wonderful texture and contrasting color for the changing leaves of many other forbs. It is surprising to view the seeds up close through a macro lens. Look at all that white feathery fluff decorating the seedstalk! So intricate with so many fine hairs. Come visit Nachusa and enjoy a late fall hike through the grasses. I recommend the Clear Creek Knolls hike, with a climb to the top of Fameflower Knob. The hike trailhead is accessible from the small parking lot on Lowden Road, just south of Flagg Road or 1.4 miles north of the visitor kiosk. Once you arrive at the base of the hill, there is no path, so make your own! Just avoid walking on top of the sandstone, for it crumbles easily. Give the short climb a try and if you do, leave us a comment on this blog about your adventure!

Today’s author is Dee Hudson, a photographer and volunteer for Nachusa Grasslands. To see more prairie images, visit her website at www.deehudsonphotography.com. By Mark Jordan It is easy to spot and identify in late autumn. The tall deciduous trees, the oaks, the hickories and others, have but a few brown leaves still clinging to their skeleton frames. Below, on shorter plants, abundant leaves remain green. A drive in the country reveals this late season green plant growing at the edge of a woodlot, deep in a forest or in abandoned fields. It is in the fall that its abundance becomes most visible. It is exotic and invasive bush Honeysuckle.  Dense Honeysuckle growth Dense Honeysuckle growth Nonnative Honeysuckles such as Amur Honeysuckle, Showy Fly Honeysuckle, Common Fly Honeysuckle and others were introduced into the United States from Eurasia more than 100 years ago. They were brought into new habitats for ornamental reasons, for erosion control and for wildlife cover. In the absence of repeated fires and in grazed and disturbed wooded areas the exotic Honeysuckles have reproduced rapidly and spread widely.  There are woodland and savanna areas now in Nachusa Grasslands where the Honeysuckle has become abundant over many decades and is disruptive to the native ecosystems. These multi-stemmed bushes can grow up to twelve feet tall and form very thick shrub layers that prevent the growth of native species by decreasing the amount of light reaching the forest floor and by using up nutrients and water in the soil. Honeysuckles are considered an allelopathic species as they release chemicals into the soil that inhibit the growth of native species. Birds that may build nests in Honeysuckle are more susceptible to predation because the Honeysuckle branches are nearer the ground than native bushes. The abundant berries, while high in carbohydrates, do not produce the fats and nutrients needed by migrating birds in the fall. I have been a steward of the East Tellabs Unit at Nachusa Grasslands since 2011. With the help of many volunteers, other stewards and the Nachusa crew, we have cut and treated thousands of Honeysuckle plants of all sizes. It is rewarding to use a pair of loppers or a saw to cut a plant near its base and treat the stump with a chemical to kill the Honeysuckle and prevent resprouting. The forest floor is exposed and sunlight may reach it for the first time in years. Other methods of attacking this invasive plant include chemically spraying the leaves, applying chemicals to the base of the plant and seasonal fires.  Painting the stems of Honeysuckle Painting the stems of Honeysuckle The work to decrease the Honeysuckles continues. A few hours working among the Honeysuckle can leave one tired, sweaty, sore, scratched and covered in burrs. Yet the tired and sore will go home feeling proud for doing a necessary task that makes a difference in the diversity and ecology of the woodlands and savannas. Each Saturday a Nachusa steward leads a volunteer workday. You might collect seeds, you might pull weeds, you might pile deadfall, or you might cut, treat, stack and burn Honeysuckle.  Mark Jordan Mark Jordan Text and Photography by Tellabs Steward Mark Jordan I love autumn. I love all the seasons, but autumn is my favorite. Even after 20 years of photographing here, I still find Nachusa Grasslands an inspiration. There's always something new, something exciting and astounding each time I'm out with the camera. There is just as much beauty visible to us in the landscape as we are prepared to appreciate. Henry David Thoreau Autumnal Tints From a photographer's perspective, the landscape can be appreciated in many different ways. Color is probably the most dominant, especially in this season of incredible color displays. Yellow and scarlet in an intensity that takes your breath away. Spectacular sunrises can occur in any season, but... To be walking along and, suddenly, looking down and seeing the mesmerizing blue of the Fringed Gentian (Gentianopsis crinita) always catches me by surprise. Just as color is an obvious and overwhelming visual aspect in the fall at Nachusa, there are occasions where the opposite can also be appreciated. The monotones of this photo give emphasis to the structure of the grasses and lend an almost otherworldly quality to the scene. Contrast is also visually arresting: large and small, soft and hard, light and dark... The light and soft textures of the seeds of the Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) contrast with the sculptural, solid shapes of the pods and stems. Pattern and texture are other elements that catch my eye. Prairie Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepsis) forms a pattern amid a sea of texture. The subtle colors and shapes show off the differing textures of these late fall plants. Look down and you may not see anything that stands out in a landscape, but, together, all of the elements reveal patterns that remind me of abstract paintings or Persian carpets. Even up close, patterns are evident, as in this Prairie Dock leaf (Silphium terebinthaceum). Look at all the varying patterns of color, branching veins, dots.... Challenging situations are another aspect of photography at Nachusa that I find inspiring. Motion is one of the most difficult to capture well. Wind can be frustrating when shooting on the prairie, but wind is an ever constant presence here. Sometimes it's best to not fight it and just go with it. This very windy fall day, I decided to try to capture the wind and not the grass it was rampaging through. In this photo of a bison moving quickly through a sumac thicket, I tried to capture the motion of the animal and not focus on the animal itself. Moving the camera slightly in the direction of the bison's movements creates a blurred, abstract image where light is caught in streaks. I find the result interesting. What do you think? And then there are those surprises when all elements just come together at once: color, contrast, texture and the right light. Autumn at Nachusa: a photographer's dream.

Today's blog is by Charles Larry, a volunteer and photographer at Nachusa Grasslands. To see more of his images visit: charleslarryphotography.zenfolio.com Every year, on the 3rd Saturday in September, Nachusa Grasslands puts on the Autumn On The Prairie festival. This tradition started in 1988 with only a couple tents and a few dozen visitors. This year's festival boasted many vendors and attracted over 900 visitors. Walking and riding tours went out throughout the day and the site was filled with activities for all ages. Lunch was catered by Oliver's Corner Market. Bison tours, such as the one above, went out from the site all day. The herd put on a good show for one wagon load after another. Walking tours explored many areas of the preserve, including Tellabs Savanna (pictured above). Among the vendors this year were many local artists. From photography to beading, each displayed their unique style and inspiration from the prairie. One tent was devoted to painters. Several gorgeous landscapes, such as the one above, were painted on–site. (Above) A visitor tries the atlatl, an ancient spear–throwing technique, at Alan Harrison's tent where Native American skills were demonstrated. The welcome tent sold 290 t-shirts! Thank you to everyone who was involved with the festival, especially to all the volunteers who put in months of effort to make this event happen every year. We look forward to seeing you all next September! Today's author is Leah Kleiman.

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed