|

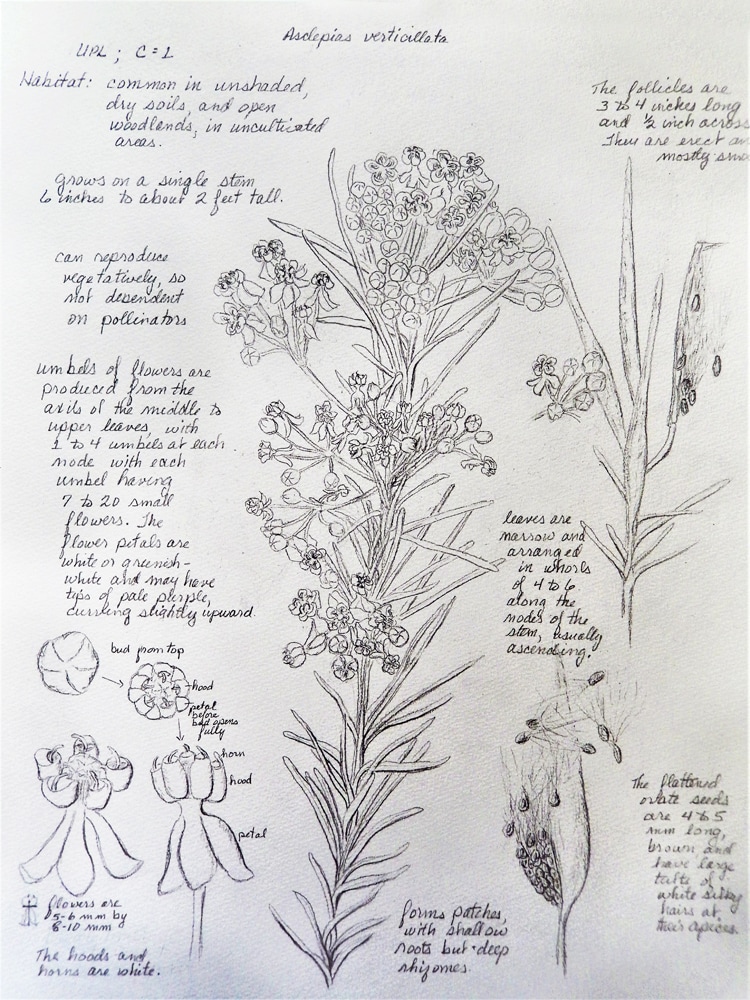

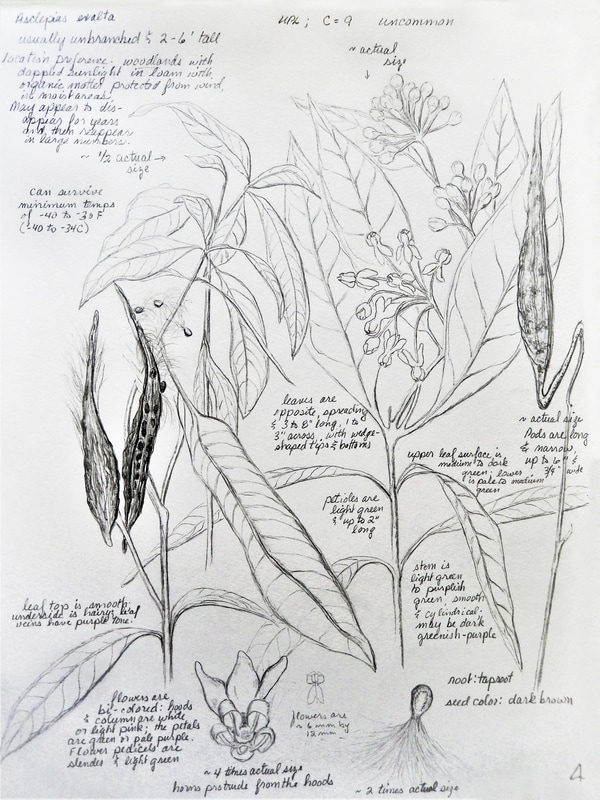

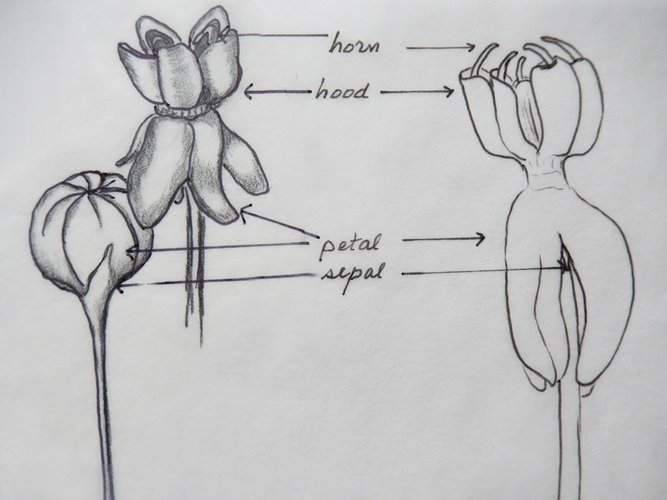

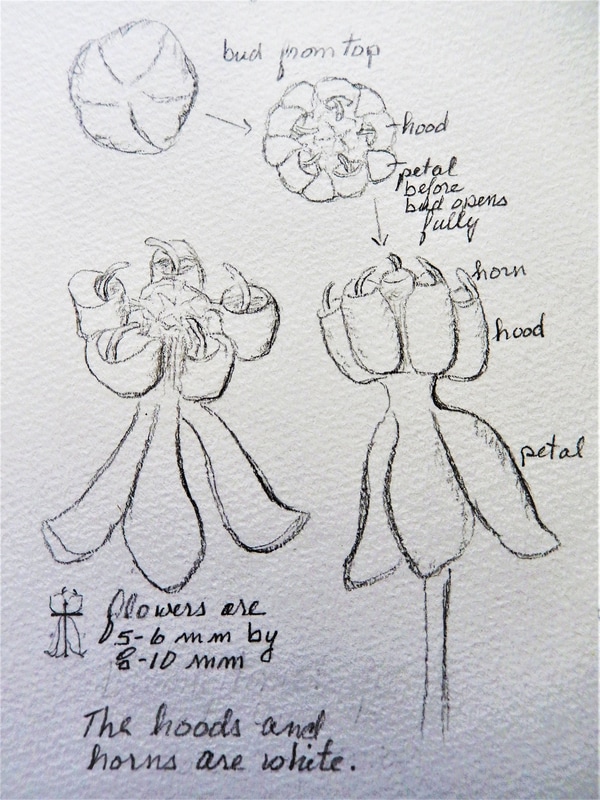

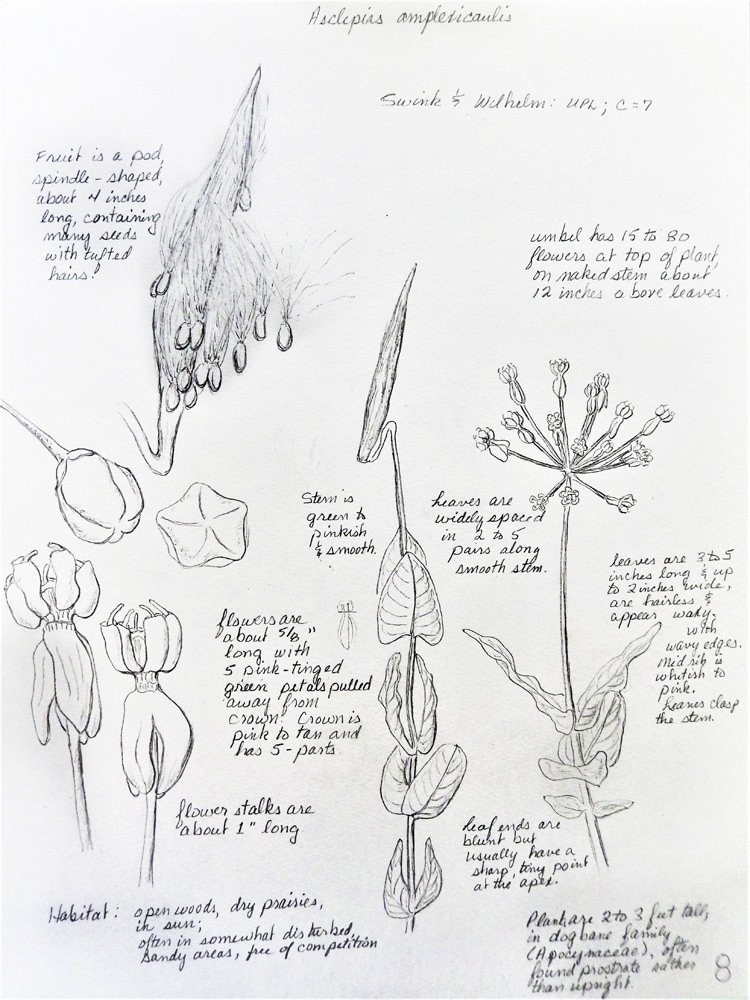

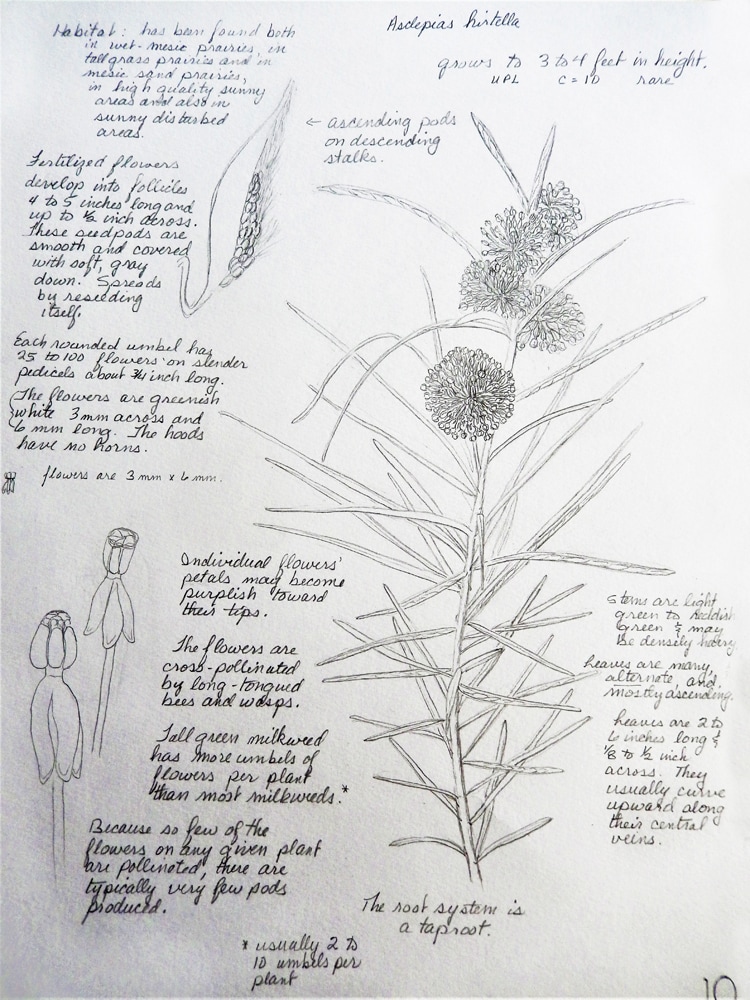

Milkweeds are a subfamily of the dogbane family (Apocynaceae). Most of us are familiar with the extreme dependency of the Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) on milkweed plants. These native perennials are the only plants that Monarch larvae (caterpillars) will eat. If there were no milkweeds, there would be no Monarchs. The Monarch butterfly is Illinois’ State Insect. In April and May, Monarchs begin arriving back in Illinois from their winter migration to Mexico. So, this is a good time to take a quick look at a few of the twenty-three species of milkweeds that are known to be native to Illinois. They are a critical part of the habitat needed by Monarchs. Milkweed is named for its white milky-looking sap, although at least one milkweed species, Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) has a clear, rather than milky, sap. At one time, various species of milkweeds could be seen growing in most any ditch, vacant lot or fence line; hence the unfortunate “weed” in its name, even though this plant genus has some of the world’s most unique flowers. The botanic name for the milkweed genus is Asclepias. The name was chosen for Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, although some milkweed species are toxic. So much for naming . . . Let’s look at milkweeds as a group to see what the various Asclepias species have in common. As we proceed, I will begin pointing out some of the characteristics that distinguish one milkweed species from another. Milkweeds are perennials, generally with leaves in pairs along the stem, or in whorls. The flowers develop in umbels (flower clusters in which all the branches come from a single point). I’ve chosen to illustrate a couple of milkweed species that have fewer flowers per umbel so that it is easier to really see the typical milkweed umbel structure, as well as the paired leaves on these particular milkweed species. Once you are aware of the umbel structure, it is much easier to look for and to recognize it, even on the milkweed species that have 25 to 40 or many more flowers per umbel, or that have multiple umbels. See samples in photos below. Note the slender leaves (about 1 inch wide) of the Swamp Milkweed, as compared to both the Common and the Purple Milkweeds above. The even more slender leaves of the Tall Green Milkweed (slightly over ½ inch wide) are whorled around the stem or alternate, rather than being paired opposites, as is the case with most of our local native milkweed species. Milkweed flowers are one of the most complex flowers in the plant world, probably second only to orchids. This discussion is limited to the most visible flower parts that are useful in identifying these amazing plants and to see how pollen is transferred. The flower structure varies somewhat by species, but they all have a vaguely hourglass shape, with each flower having five sepals (that fall back and become hidden by the petals as the bud opens) and five petals that reflex downward when the bud opens (see sketch above). Most flowers have petals and sepals, but milkweeds are unique in also having a third set of structures just above the petals: five pairs of hoods (where the nectar is) and horns surround the flower column (where the pollen is found in vertical slits there). These hoods and horns are actually modified stamen structures. See the sketches above. The sketch of the Whorled Milkweed shows the flower column that the hoods encircle, the spaces between the hoods and the slits in the flower column. Within the slits, pollinators can encounter the sticky pollen packets through which pollen is delivered to the eggs in the ovary at the base of flower column. In the video below, you can see the orange pollen baskets attached to the bumblebee's back legs; pollen was transferred to these baskets when his legs slipped into those slits in the flower column. Those leg baskets now spread pollen to the subsequent flowers this bee visits. Fertilized milkweed flowers develop seeds in follicles (pods), with each seed having a coma (cluster of silky hairs) which easily carries the seed on the wind. You are likely familiar with the Common Milkweed pods, which are warty with soft spines, and wider at one end than the other, splitting open when the seeds are ready for the wind to work its magic dispersing them. Showy Milkweed has very similar pods as Common. Other species, such as Purple Milkweed, have pods that are similarly shaped, but downy rather than spiny, or, in the case of Sullivant’s Milkweed, are smoother, with projections only on the upper half. Many milkweed species have slender, smooth pods. All have many seeds packed inside, each with its coma. As you can see in the previous and following photos, milkweed flower size, color and precise shape all vary by species. These various species also differ in their habitat preferences, from very dry to very wet, from full sun to wooded areas, from sand to heavy clay, from a preference for disturbed soil to an intolerance for it. The following four species are local native milkweeds that are relatively easy to find if you are interested in seeing them firsthand, and photographing or drawing them (no collecting please). See Recommended Hikes for maps to the search areas I’ve mentioned for each of the species highlighted below. Many milkweed species are now readily available for purchase at gardening stores or online. If you would like to help to save Monarchs and other pollinators by planting milkweed species in your yard, or at your school, park or business, be sure to purchase species suited to your growing conditions, that are not hybrids,* and that are native to the area where you plan to plant them, ideally within fifty miles. By choosing plants that have co-evolved with pollinators and other insects native to this area, you can be sure you are supporting their life cycles with needed resources. *In hybrids (and “cultivars”), instead of the simple nectar guides like those of native plants, that can be accessed with a butterfly’s long tongue, “. . . a bloom can be changed enough in scent or shape that butterflies can’t recognize them or access the nectar.” This is just one example of why using native plants is so important. From www.prairienursery.com.

Scientific Name: Asclepias incarnata General Characteristics & Habitat: typically grows to 3 to 5 feet tall; has deep underground stems; spreads via rhizomes; prefers wet soils (marshes, bogs, ditches). In proper locations, self-seeds prolifically. Flowers: multiple somewhat flat-topped clusters of flowers at tops of stems and branches; flower petals tend to be pale rose to rose-purple, with whitish hoods. Bloom time: mid-June to early September Stem, Leaves, Pods: stems are smooth and branched at the top; leaves are opposite, narrow (about 1 inch wide), oblong or lance-shaped, narrow at the base, and have short stalks. Pods are slender and papery, wrinkled, usually in pairs, terminal on stem. Finding them to view: along ditches and creeks and other sunny wet areas. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Meiners Wetlands and Clear Creek Knolls.  See the sketchbook page above for details on habitat, flowers, stems, leaves and pods. How to find them to view? Look in mostly sunny, undisturbed areas, along railroad right-of-ways, typically in drier soils. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Clear Creek Knolls and Thelma Carpenter Prairie. If you like a challenge, here are several milkweed species that are much more rare than the above species, that you may be able to locate for viewing and/or decide to purchase to grow yourself. Each is unique, even among milkweed species, in their own way.  The sketchbook page shows details on habitat, flowers, stems, leaves and pods. Where to find the poke milkweed to view? Look in dappled woods or other semi-shaded areas, in rich, moist soil. Don’t give up if you see them one year and not the next — they are known to disappear for years at a time and then reappear in abundance. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Stone Barn Savanna and Big Jump. Currently at Nachusa Grasslands, both Sand (above) and Tall Green (below) milkweeds are only known to be within the bison units. Take this as a challenge to find them elsewhere! Sand milkweed is about 2 feet tall, with the flower cluster well above its leaves, in dry, sandy soil where there is sparse vegetation. Tall Green is easy to identify (see below), and seems to like partial shade and soil with good drainage. Wishing you some happy milkweed exploring! All photos and video were taken by Betty Higby at Nachusa Grasslands, except the Short Green Milkweed pod, which was taken at Midewin. Text and sketches by Betty Higby, who is a volunteer at Nachusa.

2 Comments

Ephemeral ponds are temporary ponds of springtime, sometimes called vernal pools. Springtime, melting snow, and spring rains bring water and life to the ephemeral ponds and vernal pools at Nachusa Grasslands. Amphibians and macro invertebrates use these ponds as a nursery for their young. These small bodies of water flourish in the spring and then quietly, without notice, disappear into the heat of the summer. While they exist, they offer special advantages and challenges for the life that inhabits them. Plants and animals in ephemeral pools must be adapted to wet conditions in spring and dry conditions by early summer. Plants that thrive in vernal ponds are very often the same plants that one would find on the edge of permanent ponds. Permanent ponds overflow their banks in spring and a shoreline of sedges, grasses, and forbs begin to emerge in the cold water. These same types of plants emerge in the cold water of vernal pools. These plants will continue to thrive on the shores of a permanent pond as the water recedes and in vernal pools as the water fades and the pond dries. Frogs and salamanders seek out ephemeral ponds as safe breeding pools and nurseries for their young. A pond that dries out part of the year, or freezes entirely, prevents fish from establishing. Fish would eat amphibian eggs, small tadpoles, or small sallywogs*; they would also compete for the macro invertebrates that provide a rich source of food for the adult and juvenile amphibians. The trade-off is the young must grow fast enough to leave the pool before it dries in the summer heat. Nachusa’s ephemeral ponds have the advantage of being surrounded by a rich and diverse grassland. As the ponds dry, the young that managed to mature enough to leave the watery place of their youth, can venture forward into a land of plenty. Appetite-satisfying insects are plentiful. The tall grasses and abundant flowering plants provide camouflage and shelter. This is a sharp contrast to ponds among row crops, where the plants are a monoculture and are frequently sprayed with pesticide. Or, in the suburbs, where lawns are mowed right up to the waters edge, leaving no place to hide; tasty insects are sparse. Many times ephemeral ponds are filled, drained, or dug deeper to create a permanent pond, ruining the qualities that support unique macro-invertebrate and amphibian life. At Nachusa the challenges of survival in the natural world exist for amphibians, but without many of the artificial challenges that the modern world brings. Nachusa has many of these wonderful ephemeral ponds. They can often be located this time of year by the sounds of calling frogs. Western chorus frogs and spring peepers are the first to begin calling in late March or early April and are later joined by northern leopard frogs and American toads. Readers of the blog are likely familiar with the sound of the western chorus frog, often described as the sound of a fingernail being dragged across the teeth of a plastic comb; or its contemporary the spring peeper whose call begins with peep, peep, peep. The trill of the American toad is long and carries in the night air. The northern leopard frog with its low rumble, is followed by a bit of chuckle. The copes gray treefrog begins calling around early May; its call is a similar trill to the American toad, but instead of a long steady call, the copes trill comes in quick, short bursts often two or three at a time. Listen for calling frogs after the sun sets, when the winds are calm. One resident of Nachusa is never heard and seldom seen. The silent, but intriguing tiger salamander with its marbled skin, likely visits these ponds as a refuge and breeding site. Presently the pond waters are filled with eggs of frogs and salamanders. Soon these vernal pools will be filled with tadpoles and sallywogs* competing to be the next generation of amphibian life at Nachusa. As volunteers and staff at Nachusa restore the native landscape, ephemeral-pond-dependent species grow in population and diversity. Drain tiles throughout the preserve have been broken or removed, and low spots have been enhanced to return the natural hydrology to the land and allow spring wet areas to return; this increases the areas for amphibian populations to expand. It has been reported that the call of the plains leopard frog has recently been heard near the Tellabs ponds. If confirmed, another species can be added to the list of animals that call Nachusa home. The ephemeral ponds surrounded by plentiful grasslands preserves the ecological diversity that is the living tapestry of Nachusa Grasslands. Text and Photos by Paul Swanson

*Sallywogs used to denote salamander larvae vs. frog larvae. |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed