|

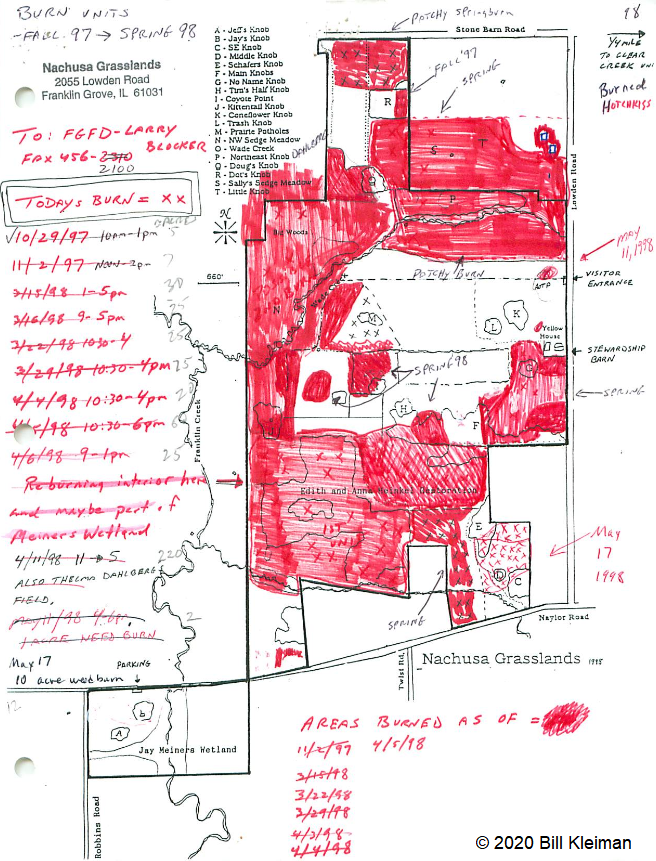

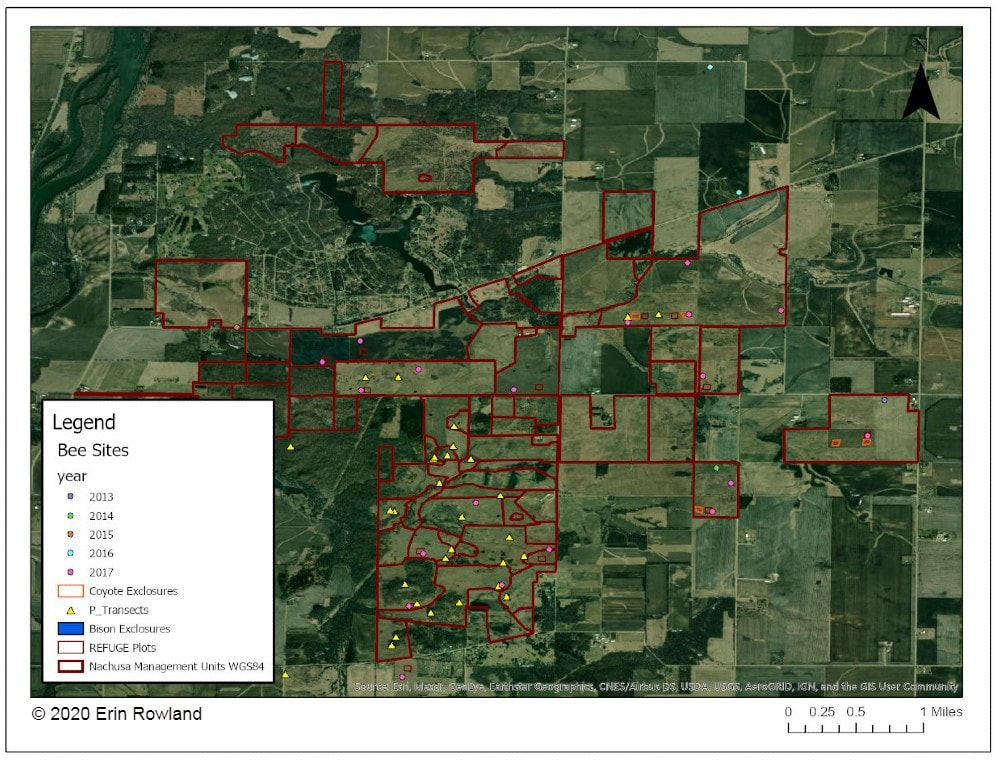

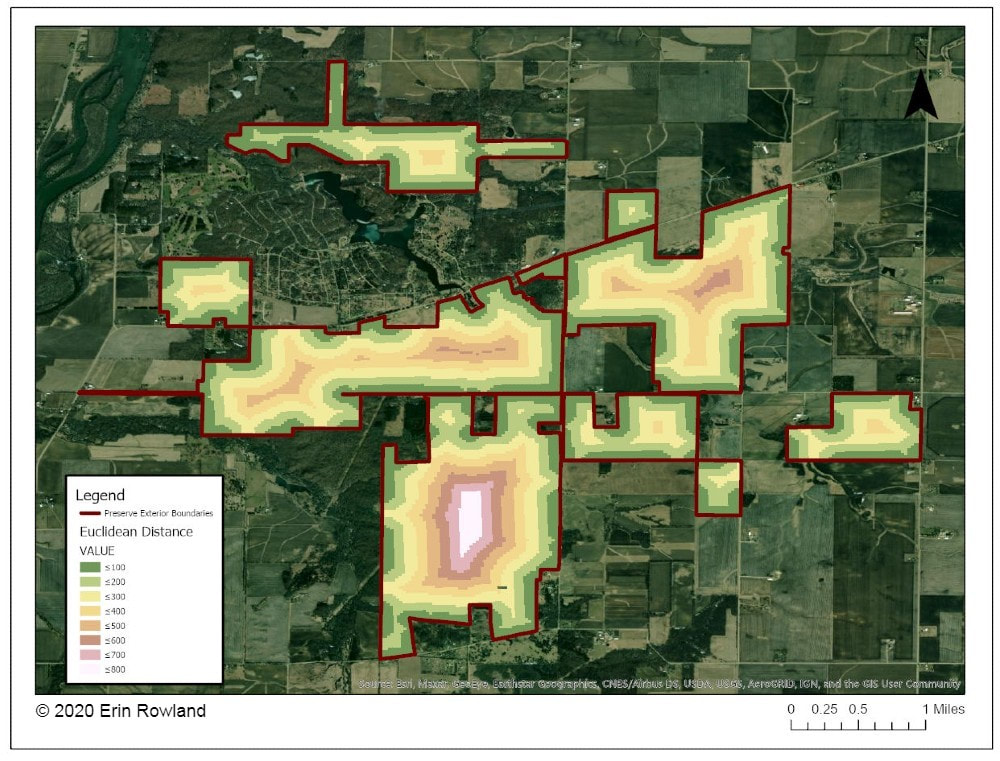

By Erin Rowland Summer Science Extern  Picturesque restorations like this are made possible by the work of volunteers and stewards on the ground. Science provides a new lens to better understand the impacts of this work. When I think of prairie restoration, I tend to think of the hands-on. I picture crews of volunteers collecting buckets of seed, or the summer crew fanned out in a line spraying weeds. Even the science done at Nachusa tends to conjure images of researchers trekking through the tallgrass after Blanding’s turtles, rodents, or butterflies. When I pictured my summer as Nachusa’s summer science extern, these were the images that filled my head. I couldn’t wait to spend my weeks under the sun trapping small mammals and surveying plant diversity. Meanwhile, the universe had other plans. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, research looked a little different this year. Many field scientists were able to conduct safe and socially distant work, while some researchers had to cancel their field seasons altogether. I was one of the unlucky ones. Instead of a summer in the field, I spent the summer at a computer. The funny thing is, this turn of events helped me to see the big picture. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a broad category of science that combines geography with other disciplines to create smart maps and analyze data throughout space and time. It’s a booming field, and it touches every aspect of our lives, whether we see it or not. GIS is used in everything from urban planning to public health to ecology. It allows us to ask and answer really interesting questions such as how the arrangement of land patches and proximity to different types of cover impact everything else on the preserve. This summer, I spent my time looking at the preserve from above in aerial imagery, trying to understand how all the pieces fit together. I spent a lot of my time converting old images of prescribed burn locations into a digital format, a process that feels a lot like a small child playing connect-the-dots. Tedious as it may be, this labor of love will help us see patterns through time in a new way. We can now easily ask how frequently certain areas of the preserve are burned and what that might mean for the plants and animals who live there.  Historically, records of prescribed burns were hand-drawn and not very precise. Our new digital fire maps are uniform and standardized, which will improve our ability to use the information. The second aspect of my work this summer was a bit more practical. Collaboration is one of the most valuable components of research at Nachusa Grasslands, and it’s part of what makes me so excited about working there. There’s such great diversity in the projects at Nachusa, as you can clearly see from the spectrum of projects funded by the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands science grants. One of my goals this summer was to compile a map of all the long-term research sites on the preserve, as well as to describe the types of data collected on these plots. By making information about data more broadly accessible, we can support better science that can benefit Nachusa and other prairie restoration sites. Researchers are better able to collaborate if they know what data exists and to whom to talk about it.  A map of long-term research sites at Nachusa will help researchers to more effectively collaborate and establish new projects more easily. The third part of my work this summer was beginning to understand the impact of human-made boundaries on a natural system. Plants and animals don’t care at all about the arbitrary places we draw our lines on a landscape. A piece of habitat is all the same to them, regardless of who owns it. This means that we have to be aware of the places where we create borders and boundaries and understand the impacts that they may have. A simple mowed path for a stewardship vehicle may seem minor to us, but might represent an insurmountable obstacle to a vole. One of the most exciting revelations of my work this summer is a success story in the tallgrass. I conducted analysis to understand how insulated different areas of the preserve are from the surrounding landscape. I created a heatmap to illustrate distance from the edge of the preserve, an attempt to classify land by how far it is from the proverbial “edge.” The results showed that the best-insulated area of the preserve is part of the original purchase that established Nachusa Grasslands. Not only was a beautiful portion of remnant prairie preserved, but the land around it was converted to create a pure prairie landscape with a buffer of protection from the surrounding agriculture and development.  This map helps us to understand how close various areas of the preserve are to non-prairie edge. We can see which areas are the most insulated from external impacts. Management happens at a variety of scales. Many decisions are made at the smallest scale: an invasive species can be removed from a part of a unit, and seeds can be collected from a rich patch of big bluestem to be planted next year. What’s harder to consider is how these seemingly small decisions work in tandem to create larger-scale impacts. The preserve looks different from above than it does on the ground. The challenge for managers is to be able to simultaneously see the prairie and the plants, as well as the forest and the trees. To meet the needs of a prairie restoration, one has to imagine the view of a turtle or a ground squirrel, in order to imagine a patch of grass as your whole world. At the same time, one must consider the big picture. Making decisions on the small-scale for the sake of specific animals or desirable plants can negatively impact the overall health of a system. What excites me the most as a researcher at Nachusa is the opportunity to do science that helps us make better decisions in restoration. By taking a step back out of the grass this summer, I had the chance to look at the preserve from a different perspective. I gained a new appreciation for the complexity of a prairie restoration project and the multi-faceted decision-making with which land managers are tasked. Now I look forward to taking my maps and figures and using them to ask more questions about how our work changes the landscape and how the landscape changes our work. Erin Rowland's ongoing research on small mammals and landscape ecology is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. To get involved withe the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. If you are interested in learning more about Erin's small mammal work, check out the recent blog by Jessica Fliginger or contact Erin to learn about opportunities to volunteer!

1 Comment

By Dee Hudson On March 7th Nachusa hosted a refresher day for the Nachusa and Middle Rock Conservation Partners fire crews. The day was sunny, and spring was in the air—a perfect day to light some prairie fires. How do you become a fire crewmember? The Nature Conservancy has three requirements for a potential fire crewmember: 1. Pass the pack test. This requires each person to carry a 24-pound pack for two miles. The trick is that the pack test must be completed in 30 minutes or less. Long-legged individuals have a bit of an advantage, while short-legged people really need to hustle. 2. Complete the S-130/S-190/I-100 online course work. These courses are self-paced and give an introduction to the basics of wildland fire training. There are questions at the end of each video section, and they must be answered correctly in order to continue to the next section. Before beginning the online course, candidates must contact Nachusa or another agency that will supervise the fire training, as a sponsor is needed to complete the online course. After the online portion is complete, there is one day of hands-on training. 3. Attend a fire refresher. Nachusa’s refresher this year focused on learning to use the pumper equipment and hand tools during live fire exercises. For more information about prescribed fire training, visit the Illinois Prescribed Fire Council website. To learn more about Nachusa’s fire program, visit the Controlled Burns page on the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website.

By Charles Larry, with a thank you to Bill Kleiman for his help. Fire! The very word can conjure up images of terror or comfort. Forest fire, wildfire, or house fire evoke terror, while campfire, hearth fire, and cooking fire suggest comfort. Fire for a prairie or savanna means renewal. Fire is a necessary element in the way these ecosystems evolved. The native peoples of the prairies were using frequent low intensity landscape fires to encourage habitats that fit their needs for hunting, food, and medicine. The natural areas we now manage are dependent on those fires continuing. Fire kills the above ground portions of small trees and shrubs, sparing the oaks and hickories, which have adapted to fire with thick bark and the ability to re-sprout as needed. After a prescribed burn, the landscape looks bleak, seemingly devoid of life. But this is an illusion. Fire sets back woody plants, encourages wildflowers and grasses, and cycles nutrients. In just a few weeks vegetation begins to sprout anew. Plants such as wild lupine, foxglove, and ferns flourish after a prescribed burn. By summer, everything is in full bloom. Wildlife, such as deer, coyotes, foxes, rabbits, squirrels, opossums, raccoons, and birds, such as wild turkeys, red-headed woodpeckers, chickadees, goldfinches, indigo buntings, not to mention the myriad insects, all benefit from the lush environment. In this photo we see some old standing oaks that died from oak wilt or some other oak disease. Autumn is seed time and root time, returning again to underground. Dragonflies mass, preparing for migration. Migratory birds, such as northern flicker, indigo bunting, and summer and scarlet tanagers also gather in flocks to begin their migrations south. Tree frogs cease singing and bury themselves under logs, rocks, or leaf litter to hibernate the winter. The air becomes cooler. Frost happens with more frequency, foretelling the coming of winter. Winter is quiet and still but by no means vacant of life and activity. Deer roam about, eating dry grasses or other plants coming up through the snow, as well as twigs and the bark of trees. They also eat acorns or hickory nuts that have not been stored away by the squirrels. Coyotes and foxes prowl for voles or mice under the snow. Because the land is blanketed with snow, it protects the seeds that have been dispersed. When the snow melts in spring, it will help to plant and nourish those seeds. Thus the cycle begins again. This week's blog was written by Charles Larry, a volunteer and photographer at Nachusa. To see more of his images, visit his photography website.

Yes! Spring fire season is here! As a Nachusa Grasslands’ fire crew member, it is time to get ready. The Nature Conservancy has three fire crew requirements:

Nachusa Grasslands held its 2018 Refresher exercise on March 10. Folks fresh out of S-130/S-190 attended, along with the regular, seasoned crew. Whatever the team member’s experience, the refresher has always been a day where we all take away lessons. First task of the day — Field test. It helps to take the test in a group. Camaraderie is regenerated as we chat and laugh. Those of the crew who benefit from being taller help those of us who are shorter by setting the pace of four miles per hour. This portion of the day has been nicknamed the “pack test” by Nachusa’s fire crew. Do we call it the pack test because something unconsciously wonderful occurs during the hike that helps reinforce communication and cohesiveness that a crew will need during an actual burn? Are we working together similar to a wolf pack, thus, a “pack” test? Hmm. Next — Classroom. This is the time to review our various burning methods and first aid/safety. This portion of the day is perhaps the most difficult because we all prefer to be outdoors. There is the benefit that someone typically brings homemade goodies to share. Finally, we head outdoors to practice! We split into groups and work through various stations.

Equipment Review. If you have ever burned somewhere else, you immediately appreciate the plethora of tools available at Nachusa. The trucks with large water tanks are helpful. The trucks are not as maneuverable as a utility vehicle (UTV), but the big tanks are great because large volumes of water are available on the fire line. In contrast to the trucks, we have UTV’s with smaller water tanks that can access tight or muddy areas. You can imagine this luxury if you have hauled a water backpack onto a fire line. The trucks and UTV’s are only a sampling of Nachusa’s equipment. Of course, equipment requires preventive maintenance. Before every fire, all vehicles and tools are inspected for common issues. For example:

Vehicle Extraction. The best way to to avoid pulling a vehicle out of the mud is to not get it stuck. Ah, comedian. Truly. . . we talk about being mindful of the terrain, when to have a vehicle in low versus high, four-wheel drive versus two-wheel, and differential lock or not. Then we simulate a stuck vehicle and practice using the new winches on the UTV’s. The new winches are nifty because they have a “remote” that you plug into the anchor vehicle and therefore operate the winch at a safer distance from the vehicles. With this method, you can get a better perspective of the extraction process and know more quickly if the mired vehicle is clear of the mud. Cool. Vehicle backup. We use the trucks for this station. When the trucks are loaded with the water tanks, hose reels, and water pumps, it is difficult to see behind the vehicle in order to back up safely. It is extremely important to have a spotter to help back up without incident — property damage or, worse, personal injury. Verbal communication and clear hand signals are necessary between driver and spotter. We practice making a straight-on backup, and then also a straight-on backup with a 90° turn — all between cones! Yikes! Spot Fire Simulation. By far, the most anticipated station of the day — working with fire! Our burn boss, Bill Kleiman, sets a fire in the prairie and radios a “spot fire” to the waiting crew, asking for resources. We respond, separately attack the fire flanks as two teams, and extinguish the spot fire as quickly as possible, always mindful of safety. The exercise is intended to remind us how to actually approach an unwanted fire, and how to quickly and purposefully move to extinguish the fire before it is out of hand. In speedy succession, we think about the crew member up front working the fire hose and “eating some smoke” — might that person need relief? Can the driver see through the smoke? Is the now blackened area cool enough to drive over? Is somebody tending the hose so that it does not catch on fire? What is the wind doing and how is the fire moving? What type of fuels are we in? Is the fire out with the first pass or do we need more resources? Is the fire completely out? Any flare ups — double check, double check, double check. We gather for our “after action” review; what was good and what could we have done better? Let’s do another! When our refresher exercises are complete, we head back to the Headquarters Barn for some snacks, beverages, more camaraderie, and end with the feeling of a day well spent. I love the whole burning process — from initial preparation to the actual burn — to witnessing the various habitats rejuvenate and thrive following the burns. Do you want to be a part of prescribed fire? Contact us, and we hope to see you on the fire line soon! This blog post was written by Gwen D., a volunteer steward at Nachusa Grasslands.

The unseasonably warm weather created a flurry of activity to prepare the fire equipment in anticipation of the weekend's controlled burn. Nachusa burns typically begin in March. With the staff committed to speaking engagements, much of the prep work fell on long–term and dedicated volunteers, Dave Crites and Mike Carr. This past week, the men worked hard and swiftly to prepare for the possible weekend burns, loading all the various equipment and pumps to the vehicles. The burn begins, as the crew uses drip torches to ignite the grass. Water pumpers follow the igniters and extinguish any fire that burns back toward fire breaks. The crew has the fire well underway. Crew members dedicated to fire suppression, put out any unwanted fire, such as around this brush pile (it will be burned later, when there is more time to watch over it). A dust devil was observed during the burn. What causes a dust devil? McKinnon (2014) explains the interesting science:

The controlled burn is typically set in a "ring" by starting at one point and sending two crews in opposite directions, working into the wind. Near the end, the blackened area is wide enough to allow the two crews to meet up in the middle of the wind side. All the "sides" of fire meet up, and with no more fuel, the flames go out! After the burn is complete, the Project Director leads a debriefing to go over the events of the day. What did we do well? Where can we improve? Here is a short video detailing some typical events that occur during a controlled burn at Nachusa. For more information, visit Nachusa's webpage about controlled burns. Today's author is Dee Hudson. Joe Richardson, Charles Larry, Kirk Hallowell, and Bill Kleiman provided the images for this post; John Schmadeke created the video. References

McKinnon, Mika, (March 30, 2014). Science of the Fiery Dust Devil Spawned by a Controlled Burn |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed