|

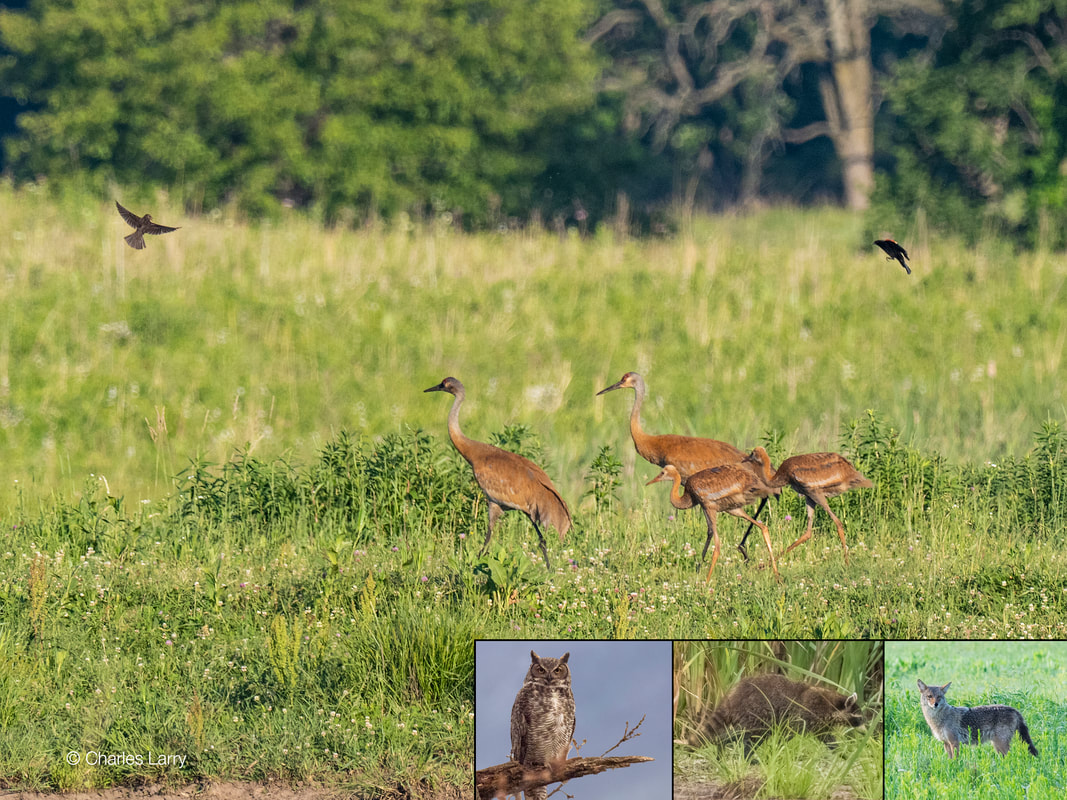

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry Spring Summer Autumn Winter

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry

By Chris Helzer Because they can’t run away, plants may seem helpless against the many large and small herbivores that like to eat them. Nothing could be further from the truth. Many plants have physical defenses such as thorns or stiff hairs to deter animals from eating them. Grasses contain varying levels of silica, which can increase the abrasiveness of their leaves and help make them more difficult to eat and digest. In addition, the chemical makeup of many plants helps make them unpalatable or toxic to potential herbivores. While herbivory is certainly a major threat, plants also have a variety of defenses against pathogens (diseases). If you’re interested in more background on this topic, here is a really nice overview of plant defenses against both diseases and herbivores. Within the last few years, there have been a couple of published studies that highlight some fantastic strategies plants use to defend themselves. In the first of those, German scientists studied a wild tobacco plant and found that when it is attacked by a caterpillar the plant releases a chemical that, in turn, attracts a predatory bug to eat the caterpillar. The production of the bug-attractant is triggered by the caterpillar’s saliva. Essentially, then, the caterpillar sets off an alarm that calls in predators to eat it. How cool is that? A second study, done at the University of Missouri-Columbia, found that a species of mustard plant could detect the vibration signature of a caterpillar chewing on one of its leaves. When the plant identified that signal, it increased production of chemicals that make its leaves taste bad to herbivores. Researchers were able to replicate and reproduce the vibrations and trigger the response in the lab. They also showed that other kinds of vibrations did not cause the plants to defend themselves, so the chemical production appeared to be a direct response to herbivory. These and other research projects help show that plants are not at all defenseless. Not only do they have strategies to make themselves more difficult to eat (toxins, spines, etc.), they can also respond when they are attacked. In prairies, there are numerous examples of plants defending themselves in interesting ways, including sunflowers that produce sweet stuff to attract predatory ants and grasses that increase their silica content under intensive grazing pressure. Of course, herbivores have evolved their own tricks to counter all those plant defenses. Several insect species, for example, have developed ways to deal with the toxins produced by milkweed plants and happily munch away on leaves that would kill other insects. Now its the milkweed’s turn to (through natural selection and over many years) come up with a response to that response. The world is pretty fascinating, isn’t it? So, the next time you’re walking through peaceful-looking prairie on a pleasant morning, remember that those little plants you’re crushing beneath your feet may not be as helpless as they appear. Sure, those plants are mostly fighting back against animals trying to eat them, but you may still find yourself an accidental victim of their defense strategies. Experienced hikers are well acquainted with the abrasive edges of grass leaves and the sharp spines on species such as roses and cacti. At one time or another, most of us have blundered into a patch of nettles or poison ivy. No, plants are certainly not helpless. Let’s just be thankful they haven’t (yet) figured out how to chase us down. A huge thank you to Chris Helzer for authoring this week's blog. Chris is The Nature Conservancy’s Director of Science in Nebraska. To enjoy more photos and discussions about prairie ecology, restoration, and management, follow Chris's blog "The Prairie Ecologist."

The Silphium sisters are all bright, cheerful, and incredibly tall. They clearly stand above all others around them and people take notice. The four Silphium sisters at Nachusa Grasslands have similarities because they are part of the same plant family, Asteraceae, but each one has unique differences. Let me introduce them to you . . .

These perennial plants in the Silphium genus are all known for their great heights. Just how tall is the compass plant? In my research I found different height reports so I decided to measure them myself. I located the tallest plants I could find in Nachusa's prairie and discovered the plants ranged in height from about 8 feet to 9 feet tall. Wow! Even more amazing is how deep the root descends into the ground. Are you ready for it? The Illinois Natural History Survey reports a depth of 10-15 feet! Amazing! Silphium perfoliatum Commonly know as the cup plant. Notice how the leaves of this second Silphium sister are opposite each other and join together at the stem to form a ‘cup–like’ shape. Silphium terebinthinaceum

Silphium integrifolium Commonly know as rosinweed. Standing around 6 feet tall rosinweed is the shortest in height of the four Silphium sisters at Nachusa. The leaves are rough and the stems have a lot of bristly hair. Rosinweed gets its name from the resin that oozes from its cut stems. The resin is rather gummy, and as a matter of fact, Native Americans used to chew it. Like the other Silphium sisters, the rosinweed has a taproot that descends 10-15 feet deep. The plant spreads by short rhizomes, so you often see the rosinweed forming a clump, as seen in the above picture. Where to see the Silphiums Once the prairie dock, compass plant, cup plant, and rosinweed were numerous across the prairies in Illinois, but as the prairies were removed these plants declined in number. Conservationist Aldo Leopold watched the last Silphium disappear from what was once a vast expanse of prairie, and he wrote this familiar quote: What a thousand acres of Silphiums looked like when they tickled the bellies of the buffalo is a question never again to be answered, and perhaps not even asked. Thanks to the restoration efforts of staff and volunteers at Nachusa, you may actually be able to see a few Silphiums tickle some bison bellies again! From July to September, one or more of the Silphiums will be in bloom. They are so easy to spot in the prairie because of their incredible heights. Look into the prairie fields and road ditches along Lowden Road, between Flagg Road and Naylor Road. The Silphiums are quite a treat to see, so let's see if you can meet all four sisters!

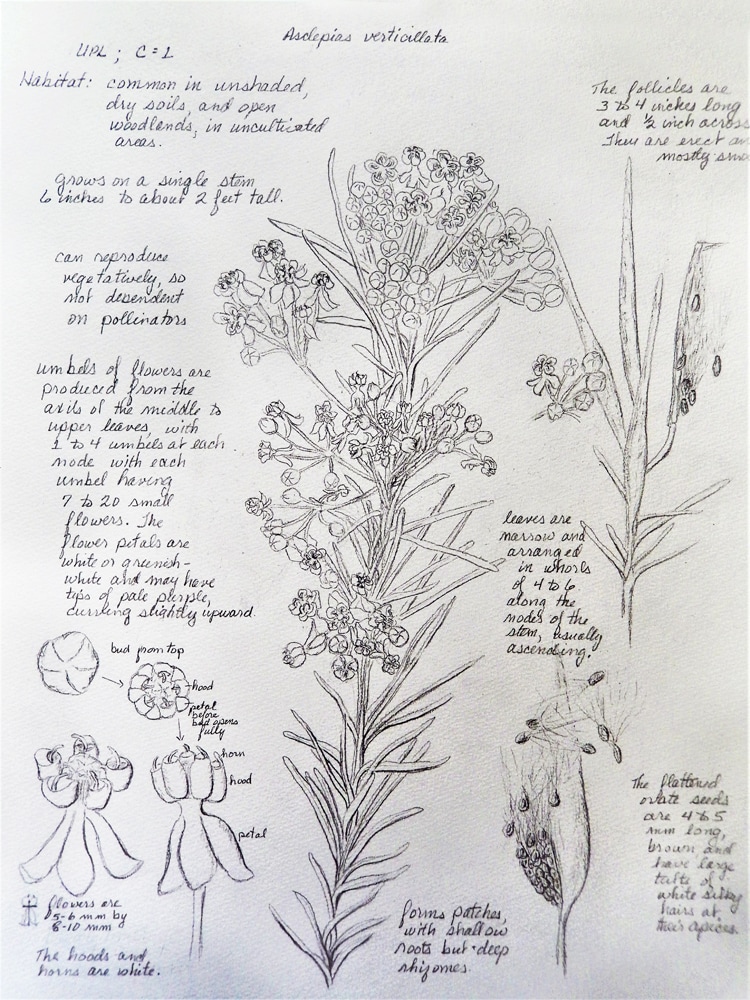

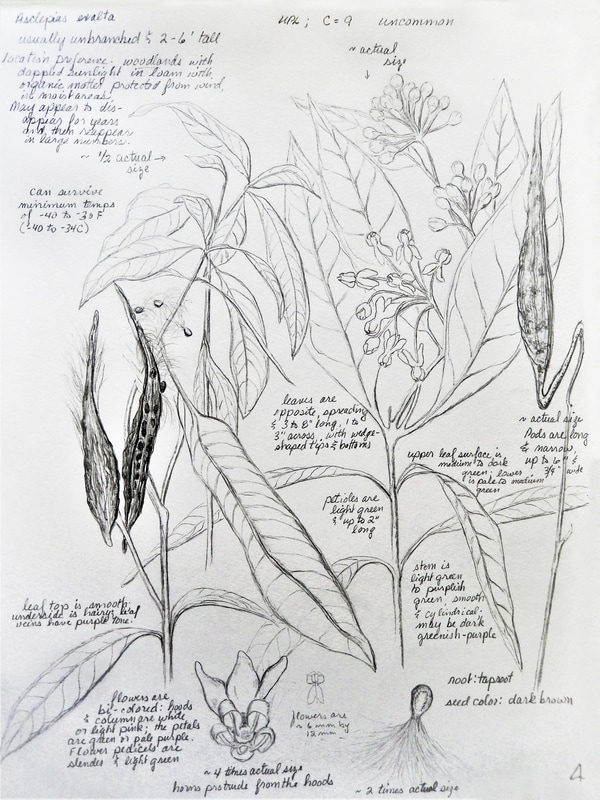

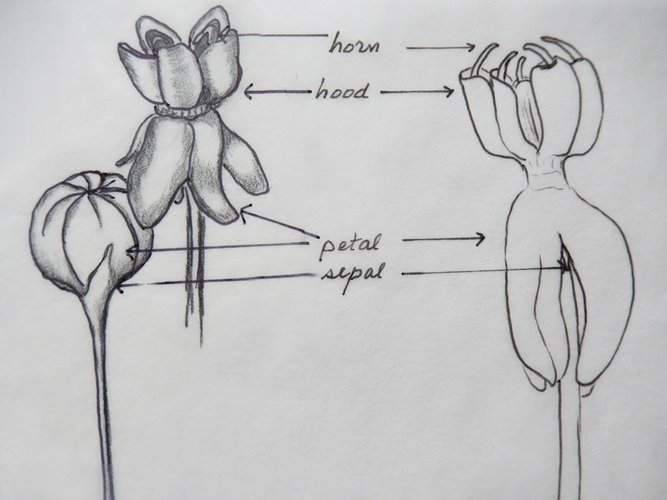

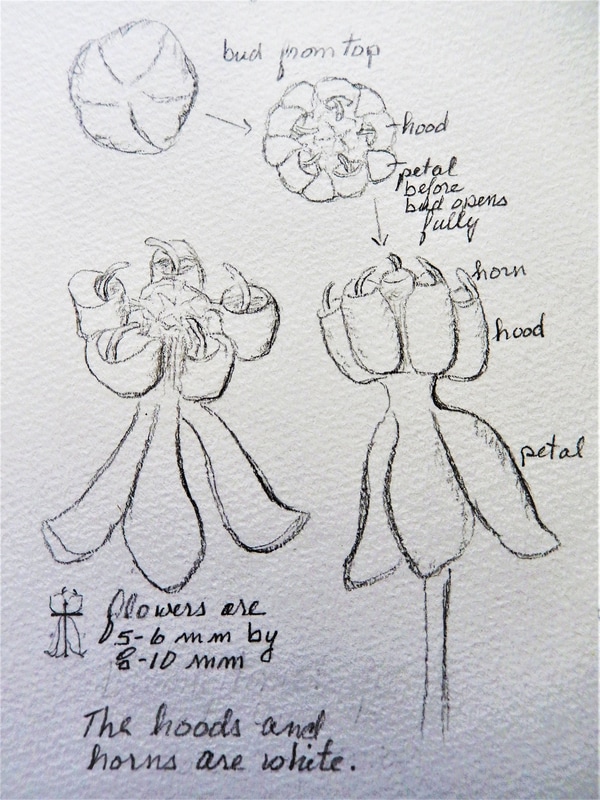

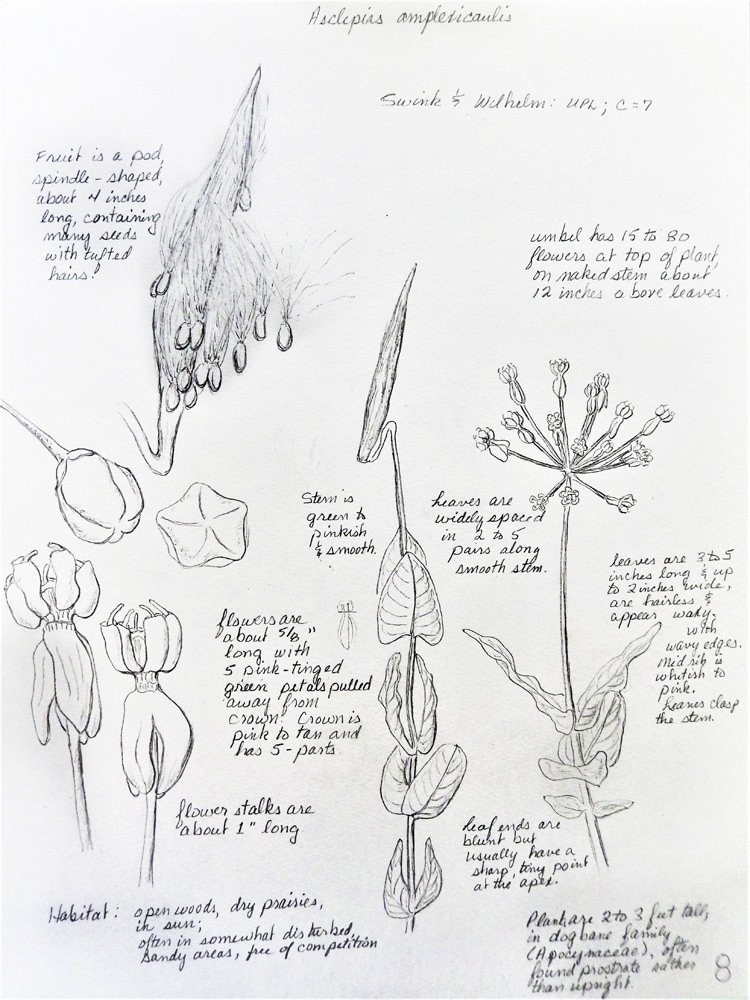

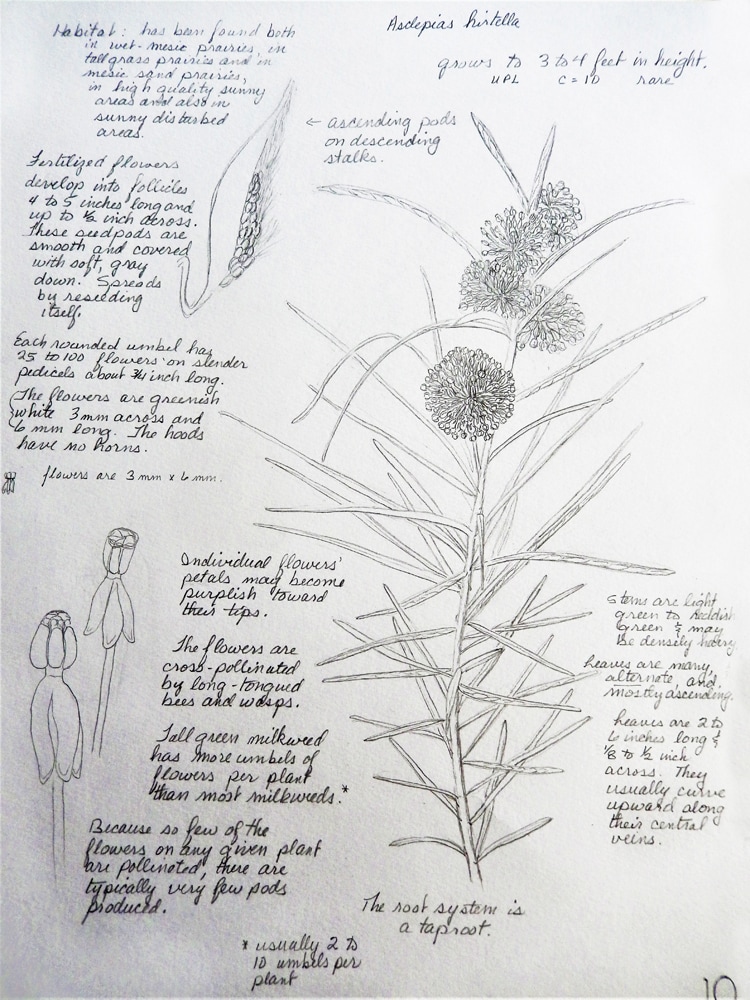

Today’s author is Dee Hudson, a photographer for Nachusa Grasslands. To see more prairie images, visit her website at www.deehudsonphotography.com. Milkweeds are a subfamily of the dogbane family (Apocynaceae). Most of us are familiar with the extreme dependency of the Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) on milkweed plants. These native perennials are the only plants that Monarch larvae (caterpillars) will eat. If there were no milkweeds, there would be no Monarchs. The Monarch butterfly is Illinois’ State Insect. In April and May, Monarchs begin arriving back in Illinois from their winter migration to Mexico. So, this is a good time to take a quick look at a few of the twenty-three species of milkweeds that are known to be native to Illinois. They are a critical part of the habitat needed by Monarchs. Milkweed is named for its white milky-looking sap, although at least one milkweed species, Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) has a clear, rather than milky, sap. At one time, various species of milkweeds could be seen growing in most any ditch, vacant lot or fence line; hence the unfortunate “weed” in its name, even though this plant genus has some of the world’s most unique flowers. The botanic name for the milkweed genus is Asclepias. The name was chosen for Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, although some milkweed species are toxic. So much for naming . . . Let’s look at milkweeds as a group to see what the various Asclepias species have in common. As we proceed, I will begin pointing out some of the characteristics that distinguish one milkweed species from another. Milkweeds are perennials, generally with leaves in pairs along the stem, or in whorls. The flowers develop in umbels (flower clusters in which all the branches come from a single point). I’ve chosen to illustrate a couple of milkweed species that have fewer flowers per umbel so that it is easier to really see the typical milkweed umbel structure, as well as the paired leaves on these particular milkweed species. Once you are aware of the umbel structure, it is much easier to look for and to recognize it, even on the milkweed species that have 25 to 40 or many more flowers per umbel, or that have multiple umbels. See samples in photos below. Note the slender leaves (about 1 inch wide) of the Swamp Milkweed, as compared to both the Common and the Purple Milkweeds above. The even more slender leaves of the Tall Green Milkweed (slightly over ½ inch wide) are whorled around the stem or alternate, rather than being paired opposites, as is the case with most of our local native milkweed species. Milkweed flowers are one of the most complex flowers in the plant world, probably second only to orchids. This discussion is limited to the most visible flower parts that are useful in identifying these amazing plants and to see how pollen is transferred. The flower structure varies somewhat by species, but they all have a vaguely hourglass shape, with each flower having five sepals (that fall back and become hidden by the petals as the bud opens) and five petals that reflex downward when the bud opens (see sketch above). Most flowers have petals and sepals, but milkweeds are unique in also having a third set of structures just above the petals: five pairs of hoods (where the nectar is) and horns surround the flower column (where the pollen is found in vertical slits there). These hoods and horns are actually modified stamen structures. See the sketches above. The sketch of the Whorled Milkweed shows the flower column that the hoods encircle, the spaces between the hoods and the slits in the flower column. Within the slits, pollinators can encounter the sticky pollen packets through which pollen is delivered to the eggs in the ovary at the base of flower column. In the video below, you can see the orange pollen baskets attached to the bumblebee's back legs; pollen was transferred to these baskets when his legs slipped into those slits in the flower column. Those leg baskets now spread pollen to the subsequent flowers this bee visits. Fertilized milkweed flowers develop seeds in follicles (pods), with each seed having a coma (cluster of silky hairs) which easily carries the seed on the wind. You are likely familiar with the Common Milkweed pods, which are warty with soft spines, and wider at one end than the other, splitting open when the seeds are ready for the wind to work its magic dispersing them. Showy Milkweed has very similar pods as Common. Other species, such as Purple Milkweed, have pods that are similarly shaped, but downy rather than spiny, or, in the case of Sullivant’s Milkweed, are smoother, with projections only on the upper half. Many milkweed species have slender, smooth pods. All have many seeds packed inside, each with its coma. As you can see in the previous and following photos, milkweed flower size, color and precise shape all vary by species. These various species also differ in their habitat preferences, from very dry to very wet, from full sun to wooded areas, from sand to heavy clay, from a preference for disturbed soil to an intolerance for it. The following four species are local native milkweeds that are relatively easy to find if you are interested in seeing them firsthand, and photographing or drawing them (no collecting please). See Recommended Hikes for maps to the search areas I’ve mentioned for each of the species highlighted below. Many milkweed species are now readily available for purchase at gardening stores or online. If you would like to help to save Monarchs and other pollinators by planting milkweed species in your yard, or at your school, park or business, be sure to purchase species suited to your growing conditions, that are not hybrids,* and that are native to the area where you plan to plant them, ideally within fifty miles. By choosing plants that have co-evolved with pollinators and other insects native to this area, you can be sure you are supporting their life cycles with needed resources. *In hybrids (and “cultivars”), instead of the simple nectar guides like those of native plants, that can be accessed with a butterfly’s long tongue, “. . . a bloom can be changed enough in scent or shape that butterflies can’t recognize them or access the nectar.” This is just one example of why using native plants is so important. From www.prairienursery.com.

Scientific Name: Asclepias incarnata General Characteristics & Habitat: typically grows to 3 to 5 feet tall; has deep underground stems; spreads via rhizomes; prefers wet soils (marshes, bogs, ditches). In proper locations, self-seeds prolifically. Flowers: multiple somewhat flat-topped clusters of flowers at tops of stems and branches; flower petals tend to be pale rose to rose-purple, with whitish hoods. Bloom time: mid-June to early September Stem, Leaves, Pods: stems are smooth and branched at the top; leaves are opposite, narrow (about 1 inch wide), oblong or lance-shaped, narrow at the base, and have short stalks. Pods are slender and papery, wrinkled, usually in pairs, terminal on stem. Finding them to view: along ditches and creeks and other sunny wet areas. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Meiners Wetlands and Clear Creek Knolls.  See the sketchbook page above for details on habitat, flowers, stems, leaves and pods. How to find them to view? Look in mostly sunny, undisturbed areas, along railroad right-of-ways, typically in drier soils. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Clear Creek Knolls and Thelma Carpenter Prairie. If you like a challenge, here are several milkweed species that are much more rare than the above species, that you may be able to locate for viewing and/or decide to purchase to grow yourself. Each is unique, even among milkweed species, in their own way.  The sketchbook page shows details on habitat, flowers, stems, leaves and pods. Where to find the poke milkweed to view? Look in dappled woods or other semi-shaded areas, in rich, moist soil. Don’t give up if you see them one year and not the next — they are known to disappear for years at a time and then reappear in abundance. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Stone Barn Savanna and Big Jump. Currently at Nachusa Grasslands, both Sand (above) and Tall Green (below) milkweeds are only known to be within the bison units. Take this as a challenge to find them elsewhere! Sand milkweed is about 2 feet tall, with the flower cluster well above its leaves, in dry, sandy soil where there is sparse vegetation. Tall Green is easy to identify (see below), and seems to like partial shade and soil with good drainage. Wishing you some happy milkweed exploring! All photos and video were taken by Betty Higby at Nachusa Grasslands, except the Short Green Milkweed pod, which was taken at Midewin. Text and sketches by Betty Higby, who is a volunteer at Nachusa.

The first day of spring 2017 has arrived! This day marks the equinox, with the sun shining equally on both the northern and southern hemispheres; the result is nearly equal hours of daylight and night. What does this mean for the prairie? Well, longer daylight means those first spring blooms are almost here! With new blades of grass already a couple inches high in the recently burned fields, April will soon bring the year’s first blooms. Let’s take a look at some of Nachusa’s beautiful spring flowers and discover where to find them. All flowers listed below are found in non–bison units and are accessible to everyone. Before the trees fill their canopies with leaves, several flowers utilize all the sunlight shining to the ground and quickly complete their whole life–cycle; then the entire plant disappears completely, leaving no trace. These short–term blooms are called spring ephemerals. The bloodroot is an ephemeral found in Nachusa's woodlands and savannas. Its showy white flower creates a great contrast against the forest floor. The plant’s name comes from the red juice that flows when any part of the plant is cut or bruised. Look for bloodroot under the trees in Stone Barn Savanna and Big Jump. Another ephemeral is Virginia bluebells, and this plant can be quite stunning growing in mass groups. They bring wonderful color to the shady parts of the woodland. Look for Virginia bluebells in moist areas of Stone Barn Savanna. Has someone been hanging their pantaloons out to dry? Certainly not! These "v-shaped" hanging flowers are found on the aptly named "Dutchman's breeches." Look for the flowers emerging from mounded fern–like foliage. Dutchman's breeches are located in the woodlands of Stone Barn Savanna. The last featured spring ephemeral is the spring beauty. Spring beauty is a very small plant found in Nachusa’s woodlands and savannas; only 3-6” tall. To identify the flower, look for the dark pink veins found on the petals. This lovely flower can be found in Stone Barn Savanna. Look for this unusual–looking flower in shady to partial–shady woodland areas. The flower can vary in color from reddish green (like pictured) to whitish green. Hike along the tracks in Stone Barn Savanna to find the jack-in–the–pulpit. Many geraniums are popular with gardeners as full–sun annuals planted in flower beds or pots. Similar in appearance, the native wild geranium is a hardy perennial flower growing in woodlands. The flowers are very showy and popular among bees and other insects. The flowers can be found in areas of full–sun, part–sun or shade. Look for it in Stone Barn Savanna. The name of this native flower is easy to remember because its blooms look like little arrows aimed at the ground. Climb along the slopes of Thelma Carpenter Prairie to find the Shooting Star. Here is a beauty that prefers sandy soils and little competition from other plants. The bird–shaped foliage gives this flower its name. This violet species is very important at Nachusa, for it is a host to the eggs and caterpillars of the state–endangered regal fritillary butterfly. Look for the violet in sandy soils at Stone Barn Savanna and Big Jump.

Looking for wildflowers is like going on a scavenger hunt. It's a lot of fun and you never know what you will find. Remember to "take only pictures and leave only footprints!" Please feel free to share your successes or adventures in the comment section below. Today’s author is Dee Hudson, a photographer for Nachusa Grasslands. To see more prairie images, visit her website at www.deehudsonphotography.com. I love autumn. I love all the seasons, but autumn is my favorite. Even after 20 years of photographing here, I still find Nachusa Grasslands an inspiration. There's always something new, something exciting and astounding each time I'm out with the camera. There is just as much beauty visible to us in the landscape as we are prepared to appreciate. Henry David Thoreau Autumnal Tints From a photographer's perspective, the landscape can be appreciated in many different ways. Color is probably the most dominant, especially in this season of incredible color displays. Yellow and scarlet in an intensity that takes your breath away. Spectacular sunrises can occur in any season, but... To be walking along and, suddenly, looking down and seeing the mesmerizing blue of the Fringed Gentian (Gentianopsis crinita) always catches me by surprise. Just as color is an obvious and overwhelming visual aspect in the fall at Nachusa, there are occasions where the opposite can also be appreciated. The monotones of this photo give emphasis to the structure of the grasses and lend an almost otherworldly quality to the scene. Contrast is also visually arresting: large and small, soft and hard, light and dark... The light and soft textures of the seeds of the Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) contrast with the sculptural, solid shapes of the pods and stems. Pattern and texture are other elements that catch my eye. Prairie Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepsis) forms a pattern amid a sea of texture. The subtle colors and shapes show off the differing textures of these late fall plants. Look down and you may not see anything that stands out in a landscape, but, together, all of the elements reveal patterns that remind me of abstract paintings or Persian carpets. Even up close, patterns are evident, as in this Prairie Dock leaf (Silphium terebinthaceum). Look at all the varying patterns of color, branching veins, dots.... Challenging situations are another aspect of photography at Nachusa that I find inspiring. Motion is one of the most difficult to capture well. Wind can be frustrating when shooting on the prairie, but wind is an ever constant presence here. Sometimes it's best to not fight it and just go with it. This very windy fall day, I decided to try to capture the wind and not the grass it was rampaging through. In this photo of a bison moving quickly through a sumac thicket, I tried to capture the motion of the animal and not focus on the animal itself. Moving the camera slightly in the direction of the bison's movements creates a blurred, abstract image where light is caught in streaks. I find the result interesting. What do you think? And then there are those surprises when all elements just come together at once: color, contrast, texture and the right light. Autumn at Nachusa: a photographer's dream.

Today's blog is by Charles Larry, a volunteer and photographer at Nachusa Grasslands. To see more of his images visit: charleslarryphotography.zenfolio.com Nachusa has an incredibly diverse plant population which can be appreciated from very early spring to late fall. Some of these plants are spectacular for a variety of reasons: some are rare, some are not common to Nachusa, and some call attention when they blanket the landscape.  Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) blooms in the woodlands in early spring. Its white blossoms provide a beautiful contrast to the dry, brown leaves left on the forest floor from the previous fall.  Birdsfoot Violet (Viola pedata lineariloba) is a rather rare plant, preferring dry, sandy soils. It blooms in spring and occurs in several places at Nachusa. Shooting Stars (Dodecatheon meadia) have an unusual structure and delicate beauty, which can be observed in spring throughout the grasslands.  Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthea leucophaea) is a truly rare plant, listed as endangered. They like moist areas and bloom in early summer in only a few spots at Nachusa.  Fringed Gentian (Gentiana procera) also likes wet, moist areas. It is a late summer bloomer and with its deep blue/purple color it is always a delightful surprise when found. Queen of the Prairie (Filipendula rubra) is rare at Nachusa, occurring in only a few places. It is one of the most spectacular plants blooming in summer if you're lucky enough to discover them. Rough Blazing Star (Liatris aspera) and Foxglove Beard Tongue (Penstemon digitalis) are common plants at the grasslands. They are quite spectacular when seen in mass and definitely have the "wow" factor. Today's blog was created by Charles Larry, a Nachusa photographer and volunteer. To see more of his images go to: charleslarryphotography.zenfolio.com

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed