|

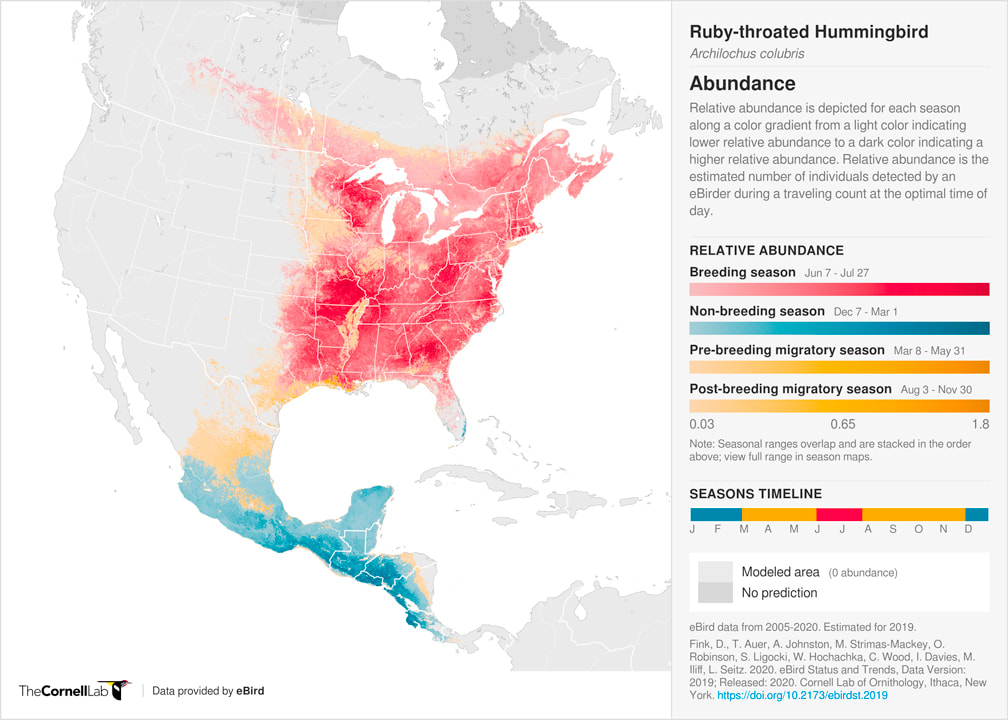

By Antonio Del Valle MS Student Spring has arrived, and with it we are in the middle of experiencing one of the many natural marvels at Nachusa: spring bird migration. Certain species of birds fly south for the winter to warmer latitudes (Florida, Mexico, and even South America) and then return to breed in northern latitudes during the summer. The specific reasons for migration depend on how far birds migrate. Short-distance migratory birds head south mainly for food. When the growing season ends here in Illinois, insects, seeds, and other food sources dwindle, which drives birds south to locations where food sources and open water are readily available. The logic and theory behind long-distance migrants (those that travel to Central and South America) appears to be more complex. According to a concise article by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the history of long-distance migration appears to be rooted in evolution. Birds that evolved to migrate long distances gained an advantage over birds that stayed in the tropics by producing more young via seasonally increased day lengths and food availability in northern latitudes.  Yellow-rumped warblers (Setophaga coronate) have been passing through northern Illinois over the past couple weeks. These warblers over winter in southern US states and Mexico, and they breed as far north as Alaska and Newfoundland. They can be found this time of the year in the wooded areas of Nachusa, including Stone Barn Savanna. By the end of May they will have moved north to their breeding grounds. Although migration occurs twice annually (both in the spring and fall), it offers a chance to see some interesting bird species that do not spend much time in this area. Starting in March, we started to see a number of birds passing through Nachusa on their way north. Notably, whooping cranes (Grus americana) were observed among the larger groups of sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis). These whooping cranes are a part of a recovering population of cranes that breed in central Wisconsin and over-winter in Florida. Thanks to conservation efforts, these federally endangered birds have started to recover (increasing from about 20 birds in the 1940s to about 600 today). Conservation efforts still continue for whooping cranes, and it is certainly a special treat to have them stopover at Nachusa. Besides cranes, high numbers of waterfowl were observed occupying the new wetland scrapes by the visitor center. In March and April there have been diving duck species observed, such as bufflehead (Bucephala albeola), ring-necked duck (Aythya collaris), and scaup. Here in April we are observing many more dabbling duck species like blue-winged teal (Spatula discors), hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), northern shoveler (Spatula clypeata), and wood duck (Aix sponsa). Though these species are visiting Nachusa now, many of them will continue northward to breeding grounds in the northern lakes of Wisconsin and Canada. As we progress through April into May, we will see more of our medium and long-distance migrants. These birds are making a long trek from Central and South America, sometimes flying long distances at once. One salient example of long-distance migration is the route of some ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris). These tiny birds are known to fly directly over the Gulf of Mexico from the Yucatan Peninsula to southern United States. That’s a 500 mile flight in approximately 20 hours! Though I haven’t seen any hummingbirds yet this spring, I bet there will be some in the area soon. As spring progresses, flowers bloom, and birds will continue moving northward. I hope you will be able to enjoy the wonders of Nachusa Grasslands and bird migration this spring. Citations & Resources:

Tony Del Valle's grassland bird research was supported in 2020 with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy.

To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

0 Comments

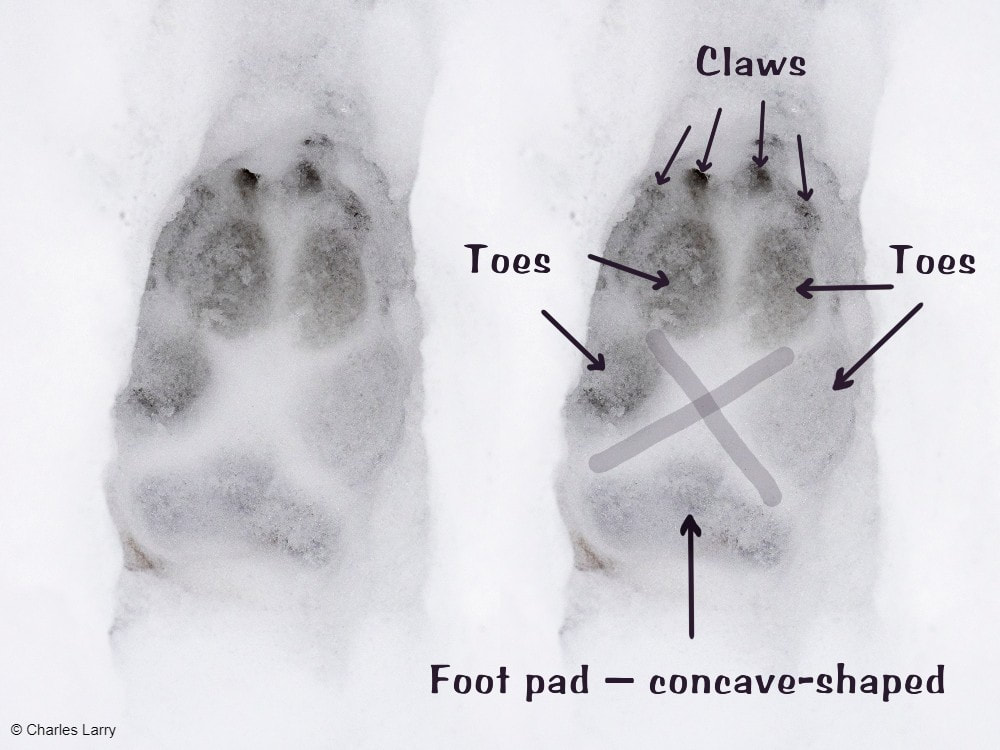

By Jessica Fliginger Field Technician “One of my daily pastimes when the snow is on the ground is to take up some trail early in the morning, and follow it over hill and dale, carefully noting every change and every action as written in the snow. . . . The trail records with perfect truthfulness everything that it did, or tried to do, at a time when it was unembarrassed by the nearness of its worst enemy. The trail is an autobiographical chapter of the creature’s life, written unwittingly indeed, and in perfect sincerity.” — Ernest Thompson Seton, Animal Tracks and Hunter Signs, 1958 Winter is the best time of year to learn about what kinds of animals are around. Whether you are at Nachusa or in your backyard, a fresh blanket of snow can reveal the conspicuous story of an animal’s life through its tracks. Learning how to identify animal tracks and tracing their routes in the snow are exhilarating outdoor winter activities that anyone can do. It starts with using your wildlife detective skills to look up, down, and around at the surrounding environment for clues, such as tracks. You may be wondering where the best places are to look for animal tracks. Truth is, the morning after a fresh snowfall (about 1 to 2 inches), you can go just about anywhere to find them. I typically find plenty of prints by wooded areas with adjoining water sources, i.e. a stream, lake, or pond. If you are a beginner naturalist, I recommend staying near home or going to a place you are familiar with, such as a bike path, park, or even as close as your backyard. One hot spot I like to frequent is my bird feeder; look under your own feeder for evidence of birds, mice, and squirrels. If you are an experienced adventurer and like walking off the beaten path, I recommend previewing a map of the location you intend to search. There are a few useful tools you might want to consider bringing on your investigation: a measuring device, a field journal, a camera, and a guide to animal tracks. If you plan on venturing into unfamiliar territory, I suggest carrying a compass and flagging tape to mark your path — and don’t forget to collect it on your way back! Here’s a tip: If you ever find yourself lost, simply re-trace your own imprints back to the starting point. Most importantly, make sure to bundle up and bring extra clothes/layers. I recommend getting an early start and checking the weather forecast prior to heading out. Since you could be trailing an animal for a long distance, be conscious of the time to avoid being out too late or getting too cold or tired. When identifying an animal track, it helps to know what animals are present in the area. I recommend using the Nachusa Grasslands Mammal Inventory to narrow down your list of possible suspects. Commonly found mammal prints include coyote, fox, opossum, deer, raccoon, rabbit, mouse, and squirrel. Occasionally, bird tracks will show up, such as turkey, crow, pheasant, and duck. Ideally, you want to be able to identify an animal’s print before following its track. After locating a clear print, carefully examine your surroundings and write down any observational notes about the habitat in your field journal — this might yield additional clues as to the identity of your suspect. Keep an eye out for signs of the animal, specifically broken twigs, chunks of bark missing from trees, hair, or animal droppings, otherwise known as scat. Next, lay your measuring device down next to the print and record its length and width. If you prefer to take your time analyzing evidence in the warmth of your home, take a photo of the print with the measuring device next to it for scale to look at later. As you proceed down the trail, feel free to take multiple photos of the track for comparison or make a sketch of it in your field journal. As you study the print, you should be able to distinguish several characteristics about it, including the number of toes, presence of nails, depth of the print, and size and shape of the front and rear paws. Canine prints are quite easy to distinguish; they have claws and are oval shaped with four toes and a concave heel pad at the bottom. The way the toes and pad are arranged should allow you to draw an “X” through the print. Likewise, deer have distinct imprints comprised of a split hoof with two toes. Furthermore, understanding an animal’s walking pattern, or gait, will help aid in its identification. There are four basic walking patterns: zig-zagger, waddler, bounder, and hopper. Zig-zaggers, or perfect walkers, leave a zig-zag patterned track and are indicative of deer, fox, coyote, dog, and cat. Waddlers have wide bodies that seem to shift from side-to-side as they walk, creating a track that consists of four prints where the rear foot does not land in the print of the front foot. Examples of waddlers include raccoons, opossums, muskrats, beavers, and skunks. Bounders, such as weasels, have long skinny bodies with short legs that expand and contract, similarly to a Slinky®, as they bound through the snow. Their tracks look like a cluster of four paws spread about a foot apart between each bound. Hoppers look as if they are leapfrogging, and this can be found in smaller critters, including rabbits, squirrels, mice, and chipmunks. Learning how to identify animal tracks is great way to enhance your observational skills and spend time outdoors during winter. Nothing is more thrilling than identifying a set of mysterious tracks. Although they may remain out of sight, animals are everywhere — get out and look!

By Elizabeth Bach Ecosystem Restoration Scientist With 2020 drawing to a close, Nachusa science has several accomplishments to recognize:

Science PublicationsScientific publications are the product of years of hard work, collecting and analyzing data as well as writing the paper. I’d like to use this blog post to highlight some of this recently published research. It has been an exciting year for Dr. Holly Jones, Dr. Nick Barber, and their lab groups. Holly and Nick began research at Nachusa Grasslands in 2013 as new faculty at Northern Illinois University (Nick is now at San Diego State University). Their work investigates restoration outcomes related to planting age, prescribed fire, and grazing. In 2020, the team has published five papers:

The Wildlife Epidemiology Lab, led by Dr. Matt Allender, at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has included Nachusa Grasslands as one of their sites in on-going health evaluations of wild turtle populations. Research scientist Dr. Laura Adamovicz has published three papers from her PhD dissertation:

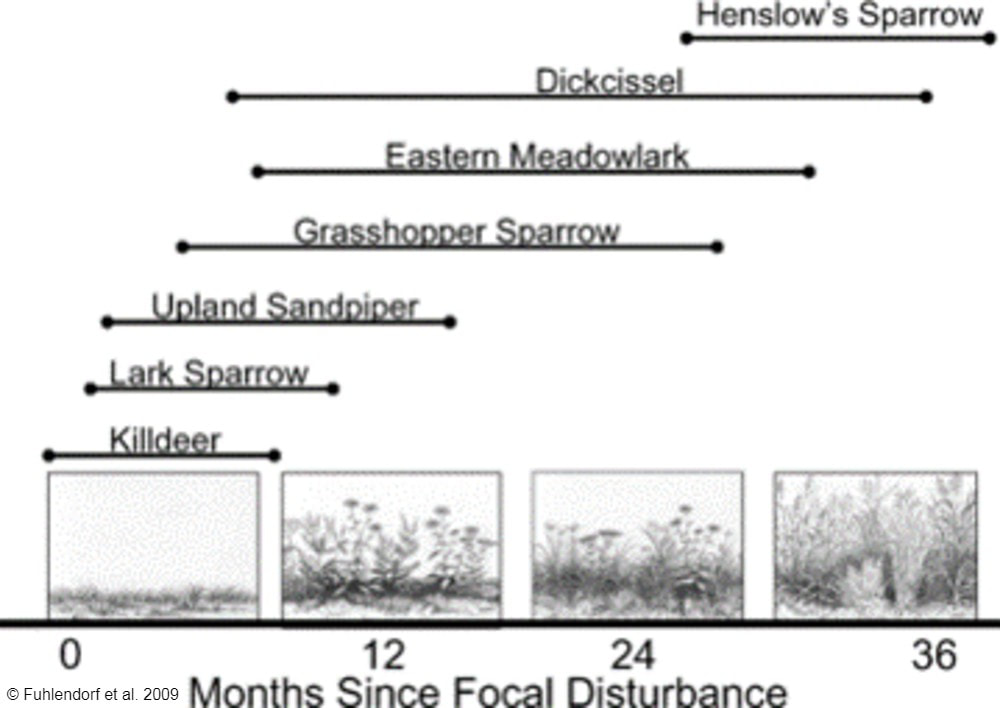

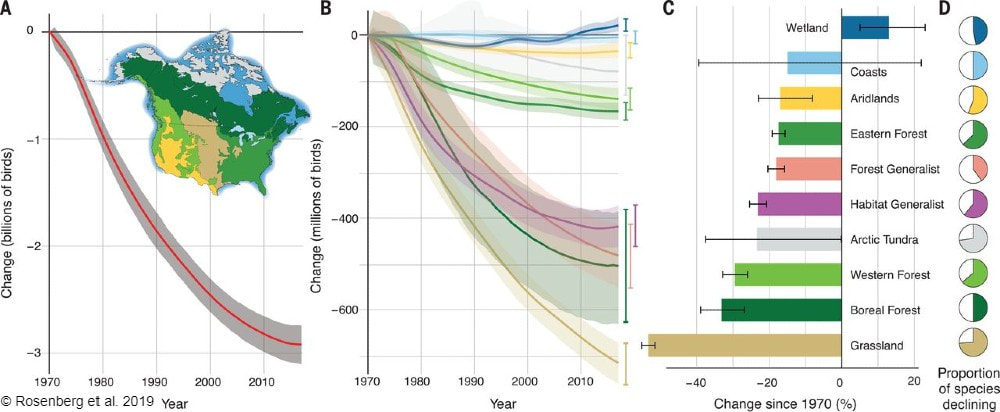

Devin Edmonds, who is a graduate student with Dr. Michael Dreslik at UI-UC and the Illinois Natural History Survey, examined Reproductive output of ornate box turtles (Terrapene ornate) in Illinois, USA. This is the first assessment of ornate box turtle reproduction in Illinois. Meghan Garfinkel earned her PhD from University of Illinois-Chicago this spring. Her research quantified crop pest suppression by songbirds. She found Birds suppress pests in corn but release them in soybean crops within a mixed prairie/agriculture system. Additional data is needed to see if these results can be applied more broadly on the landscape and across years. These initial results indicate birds could provide sizable services to agricultural land around prairie habitat. Physlis Pischl, a PhD student at Northern Illinois University, performed an elegant analysis of Plastome phylogenomics and phylogenetic diversity of endangered and threatened grassland species (Poaceae) in a North American tallgrass prairie. The work showed endangered and threatened grass species were more closely related than expected and likely evolved together in specific grassland habitats. Destruction of those habitats have resulted in many closely related species all being endangered and threatened. Read more about this study. John Vanek shared his work with Dr. Rich King surveying snake communities at Nachusa in this recent blog. John also published Observations of American Badgers, Taxidea taxus (Schreber, 1777) (Mammalia, Carnivora), in a restored tallgrass prairie in Illinois, USA, with a new county record of successful reproduction. While it is no surprise to find badgers at Nachusa, this is a new confirmed report of breeding badgers. Hana Thixton found Further evidence of Ceratobasidium serving as the ubiquitous fungal associate of Platanthera leucophaea (Orchidaceae) in the North American tallgrass prairie (open access) in her MSc research with Dr. Betsy Esselman at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Ceratobasidium fungi were by far the dominant fungal partner for EPFO, and genetic diversity of those strains was limited, indicating the fungal partners were consistent across sites. Drew Scott found Plant diversity decreases potential nitrous oxide emissions from restored agricultural soil in this research as part of his PhD dissertation at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. In this study, he found nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change, from soils at Nachusa with high plant diversity were about seven times lower than from areas with low plant diversity. View the complete list of Nachusa publications. By Antonio Del Valle MS Student  Sunrises over the tallgrass praire were a wondrous daily event to behold while surveying at Nachusa Grasslands. This summer, as part of my graduate research project at Northern Illinois University, I had the opportunity of studying some of the many bird species that call Nachusa Grasslands home. Luckily, surveying birds is an activity that you can do by yourself, which was a key factor in being able to safely conduct my research project in the midst of a global pandemic. The focus of my research is to determine how birds that breed on the prairie are impacted by some of the large scale disturbances on the prairie landscape—mainly bison herbivory and prescribed fire. Different bird species prefer different types of prairie. Species such as killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and upland sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) prefer shorter prairies that, at Nachusa, are maintained through the eating of plants by bison and frequent prescribed fires. In contrast, species such as Henslow’s sparrow (Centronyx henslowii) and sedge wren (Cistothorus platensis) prefer dense, tall prairies that are maintained through infrequent disturbances.  A figure describing the relationship between different grassland bird species presence and months since a disturbance event has occurred on the prairie. Grassland birds are a suite of species that specialize in using prairie habitat as their preferred place to breed and raise young. These species are of particular interest to me because grassland birds have experienced drastic population declines. A recent paper published in Science shows just how serious this decline has been.  Bird populations in North America have declined by three billion individuals since 1970. Grassland birds in particular have declined more than any other group of birds. But it is not all doom and gloom for these grassland birds. Thanks to the hard work put into the restoration, management, and conservation of the tallgrass prairie habitat at Nachusa Grasslands, there are bountiful places for these types of birds to breed during the summer. My research aims to help us understand more about these declining species. Preserves such as Nachusa Grasslands give me an opportunity to observe them in areas where they are still relatively prevalent.  High quality prairie restorations take a lot of hard work but provide great habitat for many declining and rare plants and animals. A typical morning of surveying birds starts out by waking up well before sunrise. I set my schedule to arrive to Nachusa around 5:30 AM in order to start surveying during peak bird activity. Coming prepared with coffee and waterproof clothes were key factors in staying awake and dry while traversing the dew-soaked prairie. Upon arriving to a survey point at the preserve, I begin surveying birds via sight with my binoculars, as well as by sound. I record all of the birds I see and hear into my field notepad for five minutes. While surveying, I record the number of individuals of each species, estimate their distance from me, and record any breeding behaviors that are displayed. Surveying in this systematic fashion allows me to look at the data later and compare what birds were seen in what areas, how many were present, and whether I can confirm that they were breeding (according to eBird’s breeding bird behavior codes). Additionally, this format allows me to compare my data to other data sets across different years and potentially different preserves/sites.  The depth of the thatch layer covering the ground is measured by using a ruler. This layer of dead plant material is important for certain species that require cover. In addition to surveying birds, I also survey vegetation and bison density through dung counts. Vegetation surveys involve measuring vegetation height, thickness of thatch layer, and percent cover of plant species. These measurements give me quantitative values to describe the vegetation structure within different areas of the preserve. Bison density is calculated through systematically counting units of dung at my survey locations. Looking at bison density in different areas of the preserve can help show where bison are spending most of their time (and eating more plants). One of my favorite birds to observe this summer was the Henslow’s sparrow. This secretive sparrow is rarely seen on the prairie, as it spends most of its summer down low in the grasses and only pops up once in a while when singing or flying. The Henslow’s sparrow song is unique as well. Cornell University’s All About Birds online field guide describes it as the simplest and shortest song of any North American bird, and to me it sounds like a faint hiccup. These sparrows have a greenish wash on their face and fine streaks on their flanks, which help to distinguish them visually from other sparrow species if you have the pleasure of catching a glimpse of them. They, along with many of the other grassland breeding birds, are now on their way back to their overwintering grounds in Central and South America. The prairies will be noticeably quieter until they begin to return in the spring again. I’m looking forward to analyzing the data collected this summer and preparing for next year’s field season over the next few months. I hope that my research can help provide knowledge to aid in the continued conservation of these grassland bird species. Nachusa Grasslands is a wonderful place to observe these birds and many other plants and animals in their native habitat. Citations & Resources: Fuhlendorf, S.D., et al. (2009). Pyric herbivory: Rewilding landscapes through the recoupling of fire and grazing. Conservation Biology 23:588–598. Rosenberg, K.V., et al. (2019). Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 366(6461):120-124. Tony’s ongoing graduate research is supported by the following sources:

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry Spring Summer Autumn Winter

By Heather Herakovich, MS Birds are known harbingers of spring. Although most stick around during the brutally cold Illinois winter, we don’t take much notice until they are everywhere in our yard, waking us up in the morning and pooping on our cars: spring time! It’s finally springtime, and at Nachusa the birds are singing, vying for territory, and finding mates. These aren’t your typical backyard birds like the American robin and northern cardinal, who are your usual early morning alarm and repeating snooze. Nachusa holds a wide variety of bird species, including some of the ones in the most need of conservation: grassland birds. They come with funny names like bobolink and dickcissel, and in all shades of brown and yellow and sometimes black. Grassland (prairie) birds are declining at a faster rate than most bird species, and a majority of this has been caused by habitat loss. Illinois is the prairie state, but only one hundredth of its original prairie remains. Places like Nachusa are doing their best to restore the agriculture fields and recreate the best prairie as humanly possible. Doing this requires a lot of hard work, hours of picking seed, planting seed, removing unwanted plants, burning portions of the prairie and mowing. The birds seem to be responding to this management fairly well. However, there is an elephant in the room, or shall I say a bison in the prairie. American bison are our national mammal, and rightfully so. These large herbivores used to roam most of the contiguous United States, until they were hunted to near extinction. I’m sure you’ve heard the story. But now they’re back! Grazing is a crucial disturbance in prairie habitat, providing habitat for a lot of species and open space for a lot of plants. But how will birds respond to this large, iconic grazer on its new home in Franklin Grove, Illinois? When I started my graduate degree at Northern Illinois University in 2013, I was able to start trying to answer that question more specifically by looking at how their nests were going to be impacted by bison. Bison can impact bird nests in a variety of ways. There are the obvious negative direct ones like trampling and dislodgement, but there are also some not-so-obvious impacts. These impacts can be either positive or negative and can affect the nesting habitat, nesting material, clutch size, and ultimately the survival of the chicks until they leave the nest (nest success). Seeing if bison are impacting nest success means I must find the nests first. This is the most difficult part. They are roughly the size of a compact disc, made from the vegetation they are in, and wickedly hard to find. If you come by Nachusa early in the morning this summer, I’m sure you’ll see me walking in the prairie, waving around a stick, and waiting “patiently” for a bird to fly from the vegetation. Although difficult, watching these nests through time is a very rewarding experience. I’ve seen nests being built, eggs being laid, chicks hatching, and chicks leaving the nest. Please don’t try this at home, though. Nests are sensitive to human disturbance, and I follow specific protocol to not influence their nest success. Bison don’t seem to be influencing their nest success either, negatively or positively. This is good news. They are one of the main sources of disturbance in the prairie, and it is a relief that they are not trampling nests of birds in decline, at least four years post-reintroduction. Watching these nests is only a part of my graduate research. I am also looking at how bison may influence nest predators, brood parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds, and what bird species are present. So far, I am not seeing anything change enough to be consider a bison impact. Time will tell if there will ever be a noticeable impact of bison on grassland birds. If I were here in ten years, I would try to find out. The beautiful prairie and bison are a great reason to visit Nachusa, but don’t forget about the birds. Sure, they all look similar and are hard to spot, but they are our harbingers of spring and make the prairie sing in the summer. Heather Herakovich is a PhD graduate student at Northern Illinois University. Heather studies grassland bird nest density, nest success, and species composition in restored plots of varying age as well as remnant control prairies. Heather is attempting to quantify the effects of bison reintroduction, prescribed fire, and restoration age on grassland bird populations at Nachusa.

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed