|

By Becky Jane Davis Nachusa Grasslands Butterfly Monitor For several years, I’ve been trying to start butterfly monitoring with the Illinois Butterfly Monitoring Network (IBMN). Everything finally came together this year. Recently I did my first butterfly monitoring at Nachusa Grasslands. Butterfly monitoring consists of counting butterflies by species, in a specific route, throughout the season. This first year, I need to identify only 25 species of butterflies. Forty years ago, I could identify more than that, but I'm a bit rusty. So, I walk at a regular pace, scanning the area, left and right on the trail, spotting butterflies. As I see one, I identify it and mark it on my field report. When I’m finished, I enter my findings in the database. It sounds easy and straightforward but my first time out, I identified about half. The rest were noted as “unknown butterflies,” so I have some learning and growing ahead of me. Things they don’t teach you in butterfly monitoring training: 1. How do you count each Monarch only once? They go here, over there, cross over the trail, and then you wonder, did I already count you? 2. Prairie plants are dense and tall. Those little butterflies can dart across the trail and into the plants and disappear before I can even see the markings or colors. 3. You need to protect yourself from ticks. That means bundling up head to toe in insect repellent-treated clothing, wearing hiking boots. Take a walking stick for uneven ground, don’t forget binoculars (if you can get them out and focused fast enough). There must be a simpler way! 4. It is good to know what a species looks like both flying and resting, but what about moving so fast, never resting, and not at an angle to fully see all four wings at once, as in the photos? 5. Back when I knew all the different species, it was because I caught them, put them in a kill jar, mounted them, and used a detailed key to identify them. No guessing! When my route is done, I have a short 10-15 minute walk back to the parking lot that allows me time to linger, get out my iPhone for a few photos, or get my good camera out to capture prairie life. I hope to get back to butterfly monitoring at least five more times this summer, hopefully more. Weather is an issue, as is distance, because I chose a location an hour away from my home. I like going to Nachusa, but it is at least a 3 hour commitment to monitor and I need to leave room in my days and flexibility so I can make that trip. Weather has not been helpful this last month. Rain, wind, and cloudiness are not good for butterfly sightings. In fact, I have rules to follow: at least 70 degrees, partly cloudy to full sun, little wind to moderate wind, and no rain. The last two weeks didn’t give many days to choose from. But I will continue and try to get more of my own photography adventures in as well. The native grasslands and prairies offer so many opportunities for interesting captures. I’m looking forward to what I can share in future blogs! Butterfly monitoring data from 7/17/2021: The route was about 50 minutes. Temperature: 77 degrees Wind speed: 9 mph. The wind was stronger at the end of the route. Sky: partly cloudy

Who are the citizen scientists, and how can I become one? Nachusa’s citizen scientists are composed of community volunteers who are passionate about their subject and want to contribute to scientific research. Do citizen scientists need prior experience or a science degree? No previous experience or scientific background is needed to volunteer, although some monitoring programs require approved initial and/or refresher trainings. Some citizen scientists may desire to seek further training and acquire new skills, while others can assist trained citizen scientists to learn the monitoring process. What citizen scientist opportunities are available at Nachusa?

How can I become a citizen scientist at Nachusa? It’s simple, just sign up on the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website. To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends of Nachusa Grasslands can also be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

1 Comment

By Peter Guiden, PhD Post-Doctoral Fellow, Northern Illinois University An ecosystem is a complex, wonderful thing. It represents many species of plants, animals, and micro-organisms interacting with each other and the air, soil, and water. It is greater than the sum of its parts. And in restoration ecology, a central goal is to put degraded ecosystems back together. However, doing so is often a challenging process—that same complexity that makes an ecosystem beautiful can also make it difficult to manage. A logical starting point is to restore the native plant community. Plants play so many important roles in an ecosystem: they provide habitat and food for animals, they exchange nutrients with microorganisms, help develop soil, and link aboveground and belowground worlds. Every plant species plays a different role in the environment, so land managers often aim to restore as many native plant species as possible, leading to high biodiversity. At Nachusa, prescribed fire and bison reintroduction are used to meet this goal, knocking back the most competitive plant species and allowing many species to coexist. Hopefully, these diverse plant communities support many diverse animal species…right? It turns out that this question isn’t often asked. It’s difficult to answer, because scientists often specialize on one group of organisms, and individually lack the tools to measure how the ecosystem as a whole responds to management. Answering this question requires assembling an Avengers-style team of researchers, who can complement each other’s interests and expertise, at the same place and time. Luckily, the Nachusa community provided an opportunity for this to happen. Through collaboration between Nachusa, Dr. Holly Jones’ Evidence-based Restoration Lab at Northern Illinois University, Dr. Nick Barber’s Community Ecology & Restoration Lab at San Diego State University, and Dr. Rich King’s lab at Northern Illinois University, we could start to look at links between plants and animals. Each of these groups brings a unique skill set to the table. Dr. Jones and her students study plants and small mammals such as wild mice and voles. Dr. Barber and his students study plants, ground beetles, and dung beetles. Dr. King and his students study larger wildlife, such as snakes. Each of these groups has collected data on these animal communities over the past decade at Nachusa, including how many species occur in these study sites, and in what abundance. This gave us an opportunity to combine our data, and ask some broad, general questions about how restoration works. Here’s a link to the study we did, if you’re interested in the technical details. We wanted to know whether the areas with the most plant biodiversity also had the most animal biodiversity, or if something else explained patterns in animal communities. If plant and animal biodiversity were linked, that would suggest that restoring diverse plant communities may lead to recovery across the ecosystem. However, if the link between plant and animal biodiversity isn’t strong, other management strategies may be needed to boost native animal species. We found that in general, the best explanation of animal biodiversity had little to do with plant biodiversity. For example, small mammal communities were most diverse in areas that hadn’t been burned for a few years, because species like voles make their habitat in thatch (dead plant litter). Similarly, snake communities were most diverse in older restorations, because certain species take a relatively long time to colonize new habitats. This isn’t to say that plant biodiversity is unimportant for animals: there were many cases where plant and animal biodiversity were linked. Small mammal communities were more diverse in habitats with a rich mixture of forbs and grasses, and the most diverse ground beetle communities were found in areas with many plant species. But on average, the effects of management on animal biodiversity were six times stronger than the effects of plant biodiversity. Why didn’t we find a strong link between plant and animal biodiversity at Nachusa? One potential explanation is our choice of study species. Snakes and beetles are carnivorous, while small mammals are opportunistic omnivores, eating both plants and animals. Perhaps animals that are strict herbivores (especially insects with very particular diets) would have been more responsive to plant diversity. But for our animals, the age or structure of the plant community seemed to be more important than the number of plant species present. It’s also important to point out that maximizing animal biodiversity may not be the most important goal in a restoration project. Protecting rare species (like the rusty patch bumblebee) or species that play an especially important role in the ecosystem (like large dung beetles that eliminate large volumes of bison dung) may take center stage. In cases where restoring animal biodiversity is important, however, it may be necessary to consider how land management affects both plants and animals. One key take-home message of this study is that restoration really works. Through the hard work of land managers, volunteers, and scientists, it is possible to recreate diverse plant and animal communities in a very agricultural landscape. While we are constantly trying to learn more about how exactly these species respond to restoration, it is important to reflect on these successes. Ecosystems continue to be mysterious in many ways, but understanding a little bit more about them may help preserve their majesty and diversity for the future. Pete Guiden's ongoing research on restoration ecology is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

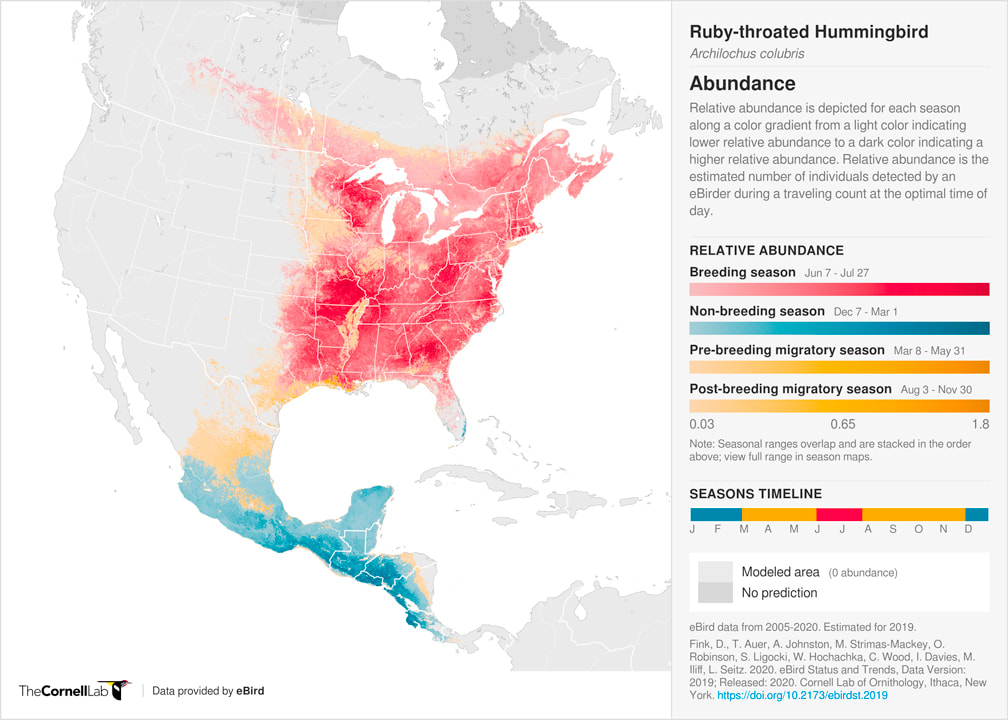

By Antonio Del Valle MS Student Spring has arrived, and with it we are in the middle of experiencing one of the many natural marvels at Nachusa: spring bird migration. Certain species of birds fly south for the winter to warmer latitudes (Florida, Mexico, and even South America) and then return to breed in northern latitudes during the summer. The specific reasons for migration depend on how far birds migrate. Short-distance migratory birds head south mainly for food. When the growing season ends here in Illinois, insects, seeds, and other food sources dwindle, which drives birds south to locations where food sources and open water are readily available. The logic and theory behind long-distance migrants (those that travel to Central and South America) appears to be more complex. According to a concise article by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the history of long-distance migration appears to be rooted in evolution. Birds that evolved to migrate long distances gained an advantage over birds that stayed in the tropics by producing more young via seasonally increased day lengths and food availability in northern latitudes.  Yellow-rumped warblers (Setophaga coronate) have been passing through northern Illinois over the past couple weeks. These warblers over winter in southern US states and Mexico, and they breed as far north as Alaska and Newfoundland. They can be found this time of the year in the wooded areas of Nachusa, including Stone Barn Savanna. By the end of May they will have moved north to their breeding grounds. Although migration occurs twice annually (both in the spring and fall), it offers a chance to see some interesting bird species that do not spend much time in this area. Starting in March, we started to see a number of birds passing through Nachusa on their way north. Notably, whooping cranes (Grus americana) were observed among the larger groups of sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis). These whooping cranes are a part of a recovering population of cranes that breed in central Wisconsin and over-winter in Florida. Thanks to conservation efforts, these federally endangered birds have started to recover (increasing from about 20 birds in the 1940s to about 600 today). Conservation efforts still continue for whooping cranes, and it is certainly a special treat to have them stopover at Nachusa. Besides cranes, high numbers of waterfowl were observed occupying the new wetland scrapes by the visitor center. In March and April there have been diving duck species observed, such as bufflehead (Bucephala albeola), ring-necked duck (Aythya collaris), and scaup. Here in April we are observing many more dabbling duck species like blue-winged teal (Spatula discors), hooded merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus), northern shoveler (Spatula clypeata), and wood duck (Aix sponsa). Though these species are visiting Nachusa now, many of them will continue northward to breeding grounds in the northern lakes of Wisconsin and Canada. As we progress through April into May, we will see more of our medium and long-distance migrants. These birds are making a long trek from Central and South America, sometimes flying long distances at once. One salient example of long-distance migration is the route of some ruby-throated hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris). These tiny birds are known to fly directly over the Gulf of Mexico from the Yucatan Peninsula to southern United States. That’s a 500 mile flight in approximately 20 hours! Though I haven’t seen any hummingbirds yet this spring, I bet there will be some in the area soon. As spring progresses, flowers bloom, and birds will continue moving northward. I hope you will be able to enjoy the wonders of Nachusa Grasslands and bird migration this spring. Citations & Resources:

Tony Del Valle's grassland bird research was supported in 2020 with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy.

To get involved with the critical on-the-ground work at Nachusa, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. By Jessica Fliginger Field Technician “One of my daily pastimes when the snow is on the ground is to take up some trail early in the morning, and follow it over hill and dale, carefully noting every change and every action as written in the snow. . . . The trail records with perfect truthfulness everything that it did, or tried to do, at a time when it was unembarrassed by the nearness of its worst enemy. The trail is an autobiographical chapter of the creature’s life, written unwittingly indeed, and in perfect sincerity.” — Ernest Thompson Seton, Animal Tracks and Hunter Signs, 1958 Winter is the best time of year to learn about what kinds of animals are around. Whether you are at Nachusa or in your backyard, a fresh blanket of snow can reveal the conspicuous story of an animal’s life through its tracks. Learning how to identify animal tracks and tracing their routes in the snow are exhilarating outdoor winter activities that anyone can do. It starts with using your wildlife detective skills to look up, down, and around at the surrounding environment for clues, such as tracks. You may be wondering where the best places are to look for animal tracks. Truth is, the morning after a fresh snowfall (about 1 to 2 inches), you can go just about anywhere to find them. I typically find plenty of prints by wooded areas with adjoining water sources, i.e. a stream, lake, or pond. If you are a beginner naturalist, I recommend staying near home or going to a place you are familiar with, such as a bike path, park, or even as close as your backyard. One hot spot I like to frequent is my bird feeder; look under your own feeder for evidence of birds, mice, and squirrels. If you are an experienced adventurer and like walking off the beaten path, I recommend previewing a map of the location you intend to search. There are a few useful tools you might want to consider bringing on your investigation: a measuring device, a field journal, a camera, and a guide to animal tracks. If you plan on venturing into unfamiliar territory, I suggest carrying a compass and flagging tape to mark your path — and don’t forget to collect it on your way back! Here’s a tip: If you ever find yourself lost, simply re-trace your own imprints back to the starting point. Most importantly, make sure to bundle up and bring extra clothes/layers. I recommend getting an early start and checking the weather forecast prior to heading out. Since you could be trailing an animal for a long distance, be conscious of the time to avoid being out too late or getting too cold or tired. When identifying an animal track, it helps to know what animals are present in the area. I recommend using the Nachusa Grasslands Mammal Inventory to narrow down your list of possible suspects. Commonly found mammal prints include coyote, fox, opossum, deer, raccoon, rabbit, mouse, and squirrel. Occasionally, bird tracks will show up, such as turkey, crow, pheasant, and duck. Ideally, you want to be able to identify an animal’s print before following its track. After locating a clear print, carefully examine your surroundings and write down any observational notes about the habitat in your field journal — this might yield additional clues as to the identity of your suspect. Keep an eye out for signs of the animal, specifically broken twigs, chunks of bark missing from trees, hair, or animal droppings, otherwise known as scat. Next, lay your measuring device down next to the print and record its length and width. If you prefer to take your time analyzing evidence in the warmth of your home, take a photo of the print with the measuring device next to it for scale to look at later. As you proceed down the trail, feel free to take multiple photos of the track for comparison or make a sketch of it in your field journal. As you study the print, you should be able to distinguish several characteristics about it, including the number of toes, presence of nails, depth of the print, and size and shape of the front and rear paws. Canine prints are quite easy to distinguish; they have claws and are oval shaped with four toes and a concave heel pad at the bottom. The way the toes and pad are arranged should allow you to draw an “X” through the print. Likewise, deer have distinct imprints comprised of a split hoof with two toes. Furthermore, understanding an animal’s walking pattern, or gait, will help aid in its identification. There are four basic walking patterns: zig-zagger, waddler, bounder, and hopper. Zig-zaggers, or perfect walkers, leave a zig-zag patterned track and are indicative of deer, fox, coyote, dog, and cat. Waddlers have wide bodies that seem to shift from side-to-side as they walk, creating a track that consists of four prints where the rear foot does not land in the print of the front foot. Examples of waddlers include raccoons, opossums, muskrats, beavers, and skunks. Bounders, such as weasels, have long skinny bodies with short legs that expand and contract, similarly to a Slinky®, as they bound through the snow. Their tracks look like a cluster of four paws spread about a foot apart between each bound. Hoppers look as if they are leapfrogging, and this can be found in smaller critters, including rabbits, squirrels, mice, and chipmunks. Learning how to identify animal tracks is great way to enhance your observational skills and spend time outdoors during winter. Nothing is more thrilling than identifying a set of mysterious tracks. Although they may remain out of sight, animals are everywhere — get out and look!

By Dee Hudson There are actually many mammals and birds active during the cold weather. What animals might you be able to see this winter? Today I’ll feature a few larger mammal species that I think you will enjoy and be most likely to see during a visit. I will also give you tips on where to look for these winter animals. Bison There is a very popular animal that draws the attention of most of our visitors, and that is our national mammal, the bison. The Nature Conservancy is committed to keeping the bison as wild as possible, so besides some minimal veterinary care during the yearly roundup, the bison breed, birth, feed, and care for themselves without human intervention. Our bison roam across 1500 acres of rolling landscape, so they may not always be visible. For your best chance to see the bison, bring a pair of binoculars and begin your search from the Visitor Center, an open-air covered pavilion that offers outstanding views of the surrounding grasslands, as well as the southern bison unit. Be sure to pick up a hiking brochure there, for the map inside indicates the bison unit locations. Many visitors can also experience a close-up view even from their cars. Just be sure to pull off to the side of the road and turn on your hazard lights. CAUTION: When a lot of snow is present, it is difficult to find parking or a pull-off. Be safe! Also, please be considerate of Nachusa's neighbors, of their property and road use. A six-foot fence surrounds the bison units. For visitor and bison safety, there is no admittance inside these bison units, by foot or by vehicle. Visitors must stay 100 feet from the bison at all times, even when separated by a fence. The bison look tame and gentle, but they are wild and unpredictable animals. Keep in mind that the adults weigh 1000-2000 pounds, are very agile, and can quickly turn and accelerate to 30+ miles per hour. Deer The white-tailed deer is another large mammal often seen at the preserve. Look for them to gather in the early morning or right before sunset. They can even be seen grazing near the bison herd. The deer enter and exit the bison units quite easily, either leaping over the fences or, more often, going under. The fence does not go completely to the ground, and this allows other animals to come and go. The deer tracks are very recognizable. They look like upside down hearts. Beaver Nachusa has beavers throughout the preserve, for these masters of engineering have been drawn to the restored wetland habitats. In winter the beavers are not hibernating, but are snuggled inside their well-insulated lodges. They have stashed a food cache of small twigs and branches in the mud at the bottom of their pond, and they use their lodge’s underwater entrance to access the supply throughout the winter. The water is not too cold for them, even in the coldest Illinois winters, for they have a thick and very warm winter coat. In January they may begin to mate, with their young born in springtime. While the water is frozen, the beavers are unlikely to be seen. However, evidence of their presence in the landscape certainly can, if you know where to look. If you look north from the Visitor Center you can spot the lodge in the restored wetland. It looks like a mound of sticks, with some plants growing on top. Other signs of beaver presence to look for are gnawed trees and beaver stumps.

Red Fox A fox’s fur is so warm that it has no problem curling up on the snowy ground. If its nose becomes too cold, the bushy tail wraps around and makes a great facemask. In the winter, the fox will mainly eat other mammals, such as rabbits and rodents, and of course, it won’t pass up any carrion. In Illinois mating occurs during the winter months, mainly January and February. The young will be born in an underground den in March and April. Look for fox in the prairies and along the woodland edges, and it’s best to begin your search close to sunrise or sunset, because they are mainly nocturnal. Opossum The opossum is the only marsupial species (a mammal with a pouch) native to Illinois, and also to North America. That alone makes this mammal interesting and unique. Then you see that they have an opposable toe and a nearly furless prehensile tail, used to grasp things and climb. With such a naked tail, it might be expected that they hibernate during Illinois winters, but they do not. However, they do stay in their dens during really cold weather, venturing out on warmer winter days. Since opossums are omnivores, winters at Nachusa provide a lot of small mammals to eat; they also eat a lot of road kill (and then occasionally become road kill themselves). For shelter, they may find a hollow log or use one of the stacked brush piles. Opossums are nocturnal, so they’re most likely to be seen in the early morning or before sunset. Look for opossums in Nachusa’s wooded areas near ponds and creeks, for they prefer to have a den near water. Coyote Many Nachusa volunteers have enjoyed a choir of coyote voices during the nighttime hours — yips, barks, and howls — so many communicating at once, that it is hard to tell how many are present. Coyotes are very active at Nachusa during the night, probably feasting mainly on the preserve’s rabbit population, as well as other small mammals. As with many of the other animals discussed, for the most success, look for the coyotes in the early morning hours or before sunset. Look for them running along the vehicle tracks that course through the units. As seen by the coyote footprints and scat, humans are not the only mammals that like to use these vehicle tracks. Come visit the preserve this winter and enjoy Nachusa’s wide-open spaces and special creatures. Let us know in the comment section whether you see any of these mammals. Please visit the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website for the preserve's full mammal inventory list.

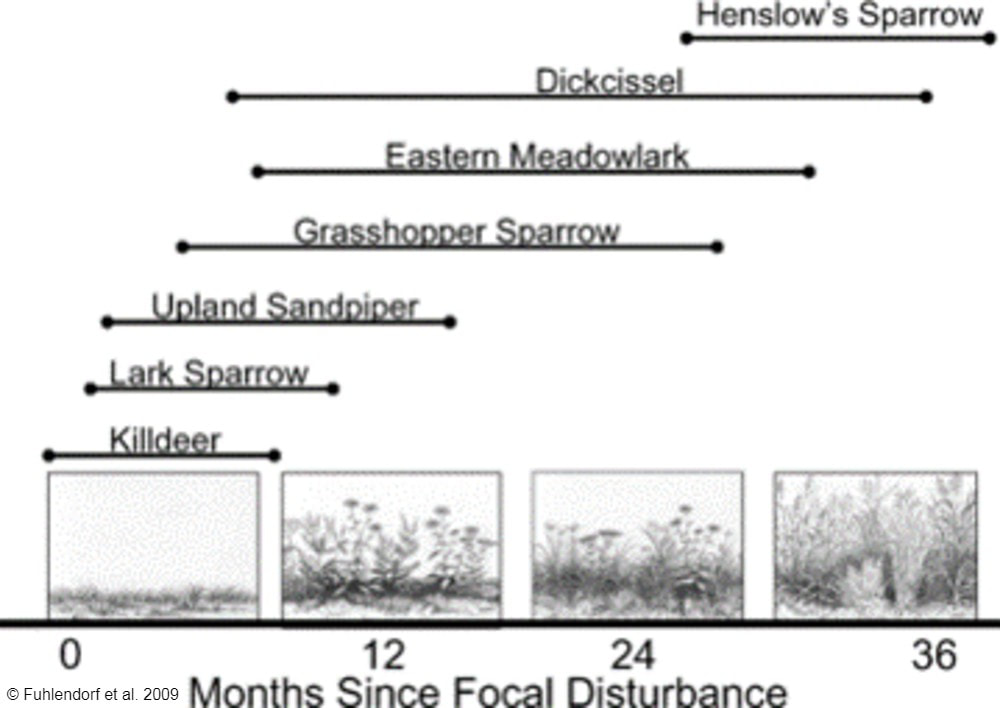

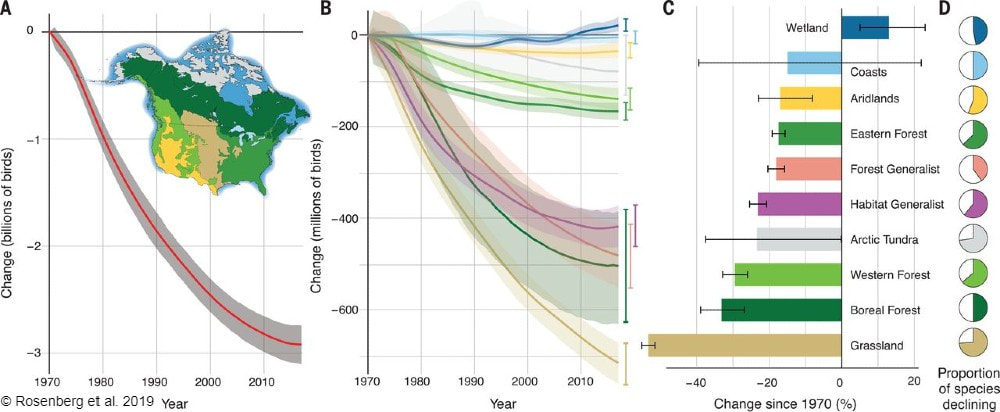

By Antonio Del Valle MS Student  Sunrises over the tallgrass praire were a wondrous daily event to behold while surveying at Nachusa Grasslands. This summer, as part of my graduate research project at Northern Illinois University, I had the opportunity of studying some of the many bird species that call Nachusa Grasslands home. Luckily, surveying birds is an activity that you can do by yourself, which was a key factor in being able to safely conduct my research project in the midst of a global pandemic. The focus of my research is to determine how birds that breed on the prairie are impacted by some of the large scale disturbances on the prairie landscape—mainly bison herbivory and prescribed fire. Different bird species prefer different types of prairie. Species such as killdeer (Charadrius vociferous) and upland sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) prefer shorter prairies that, at Nachusa, are maintained through the eating of plants by bison and frequent prescribed fires. In contrast, species such as Henslow’s sparrow (Centronyx henslowii) and sedge wren (Cistothorus platensis) prefer dense, tall prairies that are maintained through infrequent disturbances.  A figure describing the relationship between different grassland bird species presence and months since a disturbance event has occurred on the prairie. Grassland birds are a suite of species that specialize in using prairie habitat as their preferred place to breed and raise young. These species are of particular interest to me because grassland birds have experienced drastic population declines. A recent paper published in Science shows just how serious this decline has been.  Bird populations in North America have declined by three billion individuals since 1970. Grassland birds in particular have declined more than any other group of birds. But it is not all doom and gloom for these grassland birds. Thanks to the hard work put into the restoration, management, and conservation of the tallgrass prairie habitat at Nachusa Grasslands, there are bountiful places for these types of birds to breed during the summer. My research aims to help us understand more about these declining species. Preserves such as Nachusa Grasslands give me an opportunity to observe them in areas where they are still relatively prevalent.  High quality prairie restorations take a lot of hard work but provide great habitat for many declining and rare plants and animals. A typical morning of surveying birds starts out by waking up well before sunrise. I set my schedule to arrive to Nachusa around 5:30 AM in order to start surveying during peak bird activity. Coming prepared with coffee and waterproof clothes were key factors in staying awake and dry while traversing the dew-soaked prairie. Upon arriving to a survey point at the preserve, I begin surveying birds via sight with my binoculars, as well as by sound. I record all of the birds I see and hear into my field notepad for five minutes. While surveying, I record the number of individuals of each species, estimate their distance from me, and record any breeding behaviors that are displayed. Surveying in this systematic fashion allows me to look at the data later and compare what birds were seen in what areas, how many were present, and whether I can confirm that they were breeding (according to eBird’s breeding bird behavior codes). Additionally, this format allows me to compare my data to other data sets across different years and potentially different preserves/sites.  The depth of the thatch layer covering the ground is measured by using a ruler. This layer of dead plant material is important for certain species that require cover. In addition to surveying birds, I also survey vegetation and bison density through dung counts. Vegetation surveys involve measuring vegetation height, thickness of thatch layer, and percent cover of plant species. These measurements give me quantitative values to describe the vegetation structure within different areas of the preserve. Bison density is calculated through systematically counting units of dung at my survey locations. Looking at bison density in different areas of the preserve can help show where bison are spending most of their time (and eating more plants). One of my favorite birds to observe this summer was the Henslow’s sparrow. This secretive sparrow is rarely seen on the prairie, as it spends most of its summer down low in the grasses and only pops up once in a while when singing or flying. The Henslow’s sparrow song is unique as well. Cornell University’s All About Birds online field guide describes it as the simplest and shortest song of any North American bird, and to me it sounds like a faint hiccup. These sparrows have a greenish wash on their face and fine streaks on their flanks, which help to distinguish them visually from other sparrow species if you have the pleasure of catching a glimpse of them. They, along with many of the other grassland breeding birds, are now on their way back to their overwintering grounds in Central and South America. The prairies will be noticeably quieter until they begin to return in the spring again. I’m looking forward to analyzing the data collected this summer and preparing for next year’s field season over the next few months. I hope that my research can help provide knowledge to aid in the continued conservation of these grassland bird species. Nachusa Grasslands is a wonderful place to observe these birds and many other plants and animals in their native habitat. Citations & Resources: Fuhlendorf, S.D., et al. (2009). Pyric herbivory: Rewilding landscapes through the recoupling of fire and grazing. Conservation Biology 23:588–598. Rosenberg, K.V., et al. (2019). Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 366(6461):120-124. Tony’s ongoing graduate research is supported by the following sources:

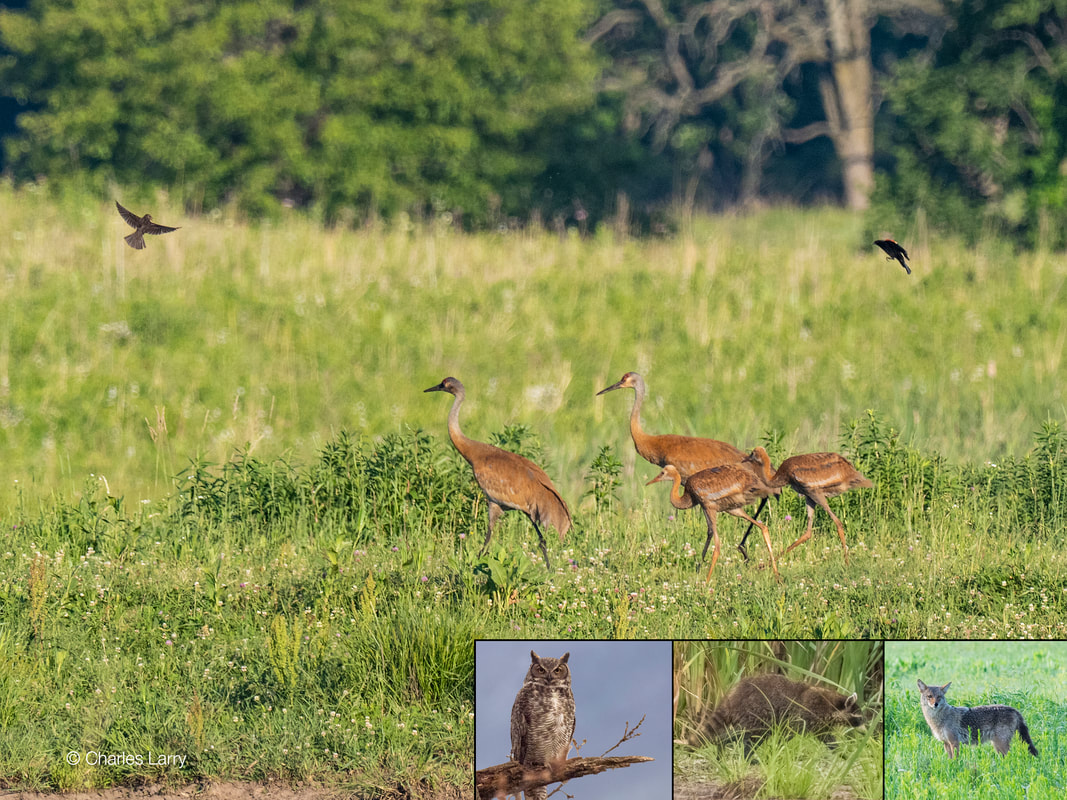

By Charles Larry Nachusa Volunteer The sound of the sandhill crane seems to echo across an immense gulf of antiquity. Cranes evolved during the Eocene (56-33.9 million years ago). The earth was warmer and wetter during this time, and in North America, with vast areas of prairie, savanna, marsh, and shallow inland seas, it was ideal habitat for the ancient ancestors of modern cranes. This early crane was likely a relative of the crowned crane now found in Africa. Fossil remains of this early crane have been found in North America, dating some 10 million years. But then the climate in North America started to cool, eventually bringing about the Ice Ages. These events saw the disappearance of this early crane on the continent. At some point a relative of the modern crane, one suited for cooler climates, evolved here. The earliest fossil of this later crane was a bone almost identical to that found in modern sandhills. This fossil was found in Florida, dating back 2.5 million years. Modern sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) are divided among two and six geographical subspecies, depending on sources. Generally, there are the greater and lesser sandhills. Nachusa Grasslands has had sandhill cranes stop over for brief periods over several years. In August of 2018, even a pair of whooping cranes stopped and then moved on! As far as is known, this is the first time that a pair of sandhills have nested and raised two colts (as the young sandhills are called) at Nachusa. It is usual for sandhill cranes to lay two eggs, a few days to a week apart, but it is rare that both colts will live to fledge. Some reasons as to why only one colt survives are various predators, lack of sufficient food, and sometimes the aggression of the older crane toward its slightly younger sibling. At Nachusa both of the young have fledged and are flying. Sandhill cranes usually mate for life. They become sexually mature at two years old but four or five years old is more likely to be when mating begins. Sandhills are well known for their "dancing" during mating season. This behavior is not fully understood, as cranes of any age may dance at times not related to breeding season. It is thought to also be a way of working off aggression. Both sexes participate in the building of the nest, constructed in or near water. Nests are composed of plant material found near the nesting site, such as cattails, sedges, rushes, and grasses. Nests can be six feet in diameter. At breeding time both sexes "paint" their feathers with clay and mud. The birds are normally gray in color, but the painting changes the feathers to brown. This is thought to be a camouflaging technique to blend in with the nesting site. Both parents incubate the eggs. While one sits on the nest, the other is either standing guard or gathering food. The female usually sits on the nest during the night. Hatching is about a month after laying. After hatching, the cranes abandon the nesting site, moving to a hidden spot somewhere still near water. The parents are fiercely protective of the young. Many predators are a danger to either the eggs or the colts. Among them are coyotes, foxes, raccoons, owls, and various hawks, all of which inhabit Nachusa Grasslands. Sandhills eat a variety of food, from insects such as grasshoppers or dragonflies, to aquatic plants and tubers, to small mammals such as mice, to snakes and worms. They will even eat the eggs of other birds, such as red-winged blackbirds, rails, and ducks. More recently, sandhills have learned to forage in cornfields and will often flock in vast numbers doing this. During breeding season, they are very territorial with an average territory range of about 20 acres. Until the cranes abandon the nesting site, where they are more or less isolated, they will defend this territory from other sandhills and predators by various aggressive displays and even fighting. By late summer the sandhills will probably move to an area where there is a larger crane population and more abundant food to fatten up for migration, which will happen sometime in the fall. The juveniles will stay with the parents during migration and through the winter. Sometime in the following spring they will separate from their parents and go out on their own. The main winter flyways for migration in this area are either south to Georgia or Florida or over to Texas. Sandhill cranes are threatened, as is true of cranes the world over. Climate change is one major threat. Droughts have become much more frequent, and wetlands are disappearing. In some states cranes are hunted. In the past, this resulted in the extinction of sandhills from Washington State in 1941. They have now been reintroduced to this state in small numbers. Farming conversion to incompatible crops (soybeans) over crops like corn also threatens cranes. Probably the biggest threat is from loss of habitat from urbanization and development. The sandhill crane is a magnificent bird. It would be tremendously sad if someday the sandhill crane were to join the thousands of species disappearing from our planet. To hear no more the sound of this bird, which author Peter Matthiessen says is "the most ancient of all birds, the oldest living bird species on earth." Sad indeed. Sources: Johnsgard, Paul A. A Chorus of Cranes: the Cranes of North America and the World. University of Colorado Press, 2015. Forsberg, Michael. On Ancient Wings. University of Nebraska Press, 2004. Matthiessen, Peter. The Birds of Heaven, North Point Press, 2001. Useful websites: If you would like to play a part in habitat restoration for sandhill cranes at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays, or give a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to support the ongoing stewardship at Nachusa.

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed