|

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry SpringSummerAutumn Winter

3 Comments

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry SpringSummerBy Charles Larry Friends of Nachusa Grasslands Board It was the Greek philosopher Empedocles (c.450 BCE) who first presented the idea of the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. He did not call them elements, but roots, and conceived of these not in terms of the physical properties we associate with the words, but as forms of energies whose various combinations make possible the structure of the physical world. This idea was later amplified by Plato, and then, especially, Aristotle. For the purpose of this blog post, however, earth, air, fire, and water are being used more as a conceit to imaginatively explore the elements as they may (loosely) apply to Nachusa. This exploration, in part, will utilize stories from Greek mythology. EarthHeavy, dense, solid: earth. As Gaia the earth is the foundational mother of all living things. The name Gaia is now associated with many environmental concerns. Is there any North American mammal more evocative of earth than a bison? Massive, strong, brown in color, the bison seems sculpted of earth. Rock: the bones of the earth. Nachusa's rock formations are mainly St. Peter Sandstone, which is composed of sand that once rested on the bottom of ancient seas. Over billions of years this sand sediment compacted and eroded, and after extensive land mass shifts with tectonic and glacial activity, the rock became exposed and left as outcrop. The earth with its layer of soil, giving foundation and nutrients and collecting moisture, provides growing things the necessities of life. The earth establishes a stable environment for plants, animals, and all creatures of the air. AirLight, open, space: air. Air has been called the breath of life. It surrounds the planet in a protective layer and is a requirement for most living things. In The Odyssey, Aeolus, keeper of the winds, put all of the winds except the west wind in a bag and gave it to Odysseus. The west wind would take Odysseus and his men directly to their island home of Ithaca. But the men, thinking it was some treasure that Odysseus was keeping for himself, opened the bag and let loose the winds which drove them far from home, thus taking an additional ten years to reach home after having fought in Troy for ten years. There are times at Nachusa when it seems that bag has been opened on the prairie. The early pioneers, traveling across the tall grass prairie and observing the undulating waves of grasses caused by the wind, called it a "sea of grass." Wind also helps disperse seeds, such as the lithe milkweed seed. Mankind, observing birds and flying insects, dreamed of taking to the air long before it became a reality. Daedalus, who designed the labyrinth imprisoning the Minotaur, himself became imprisoned, along with his son Icarus, to keep the secret of the labyrinth. Daedalus crafted wings made of wax so that he and Icarus could escape. This succeeded until Icarus, in his youthful headiness, flew too close to the sun, melting the wings, thereby plunging him into the sea, resulting in his death. There are times when the air, the sky with its cloud formations seems to be on fire. FireHot, expansive, light: fire. Fire can be both constructive and destructive. In Greek mythology, Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to mankind as a gift, thereby creating technology and civilization. For this act he was punished by the gods by being chained to a rock, where an eagle each day ate his liver, which grew back overnight, only to be eaten again, over and over. At Nachusa, fire usually means a prescribed burn. The prairie, like the Phoenix, needs fire for renewal. Our most pervasive source of fire/light is the sun. Sunlight is needed for plants to photosynthesize. Illuminating everything, the sun can seemingly perform magical transformations, such as becoming like molten gold on water. WaterCold, contractive, fluid: water. Most of our planet is covered by water. Perhaps the most versatile of the elements, water can exist in different states. As a fluid it is water, as a gas it is steam or mist, and as a crystalline solid it is ice. In Greek mythology it is Poseidon who rules the waters. Better known by his Roman name: Neptune, he is the Old Man of the Sea, covered by scales and holding a trident. Poseidon is the protector of all who live in the waters of the earth. It is Nachusa's ponds and streams which provide the life-giving element to all the creatures at home here. The most common source of water at Nachusa is, of course, rain. Life-nourishing rain sweeps across the prairie and savanna in storms. In winter, snow often blankets the land with needed moisture. Water: the lifeblood of the earth. If you would like to volunteer at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays.

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry SpringSummerAutumnWinterBy Dee Hudson There are actually many mammals and birds active during the cold weather. What animals might you be able to see this winter? Today I’ll feature a few larger mammal species that I think you will enjoy and be most likely to see during a visit. I will also give you tips on where to look for these winter animals. Bison There is a very popular animal that draws the attention of most of our visitors, and that is our national mammal, the bison. The Nature Conservancy is committed to keeping the bison as wild as possible, so besides some minimal veterinary care during the yearly roundup, the bison breed, birth, feed, and care for themselves without human intervention. Our bison roam across 1500 acres of rolling landscape, so they may not always be visible. For your best chance to see the bison, bring a pair of binoculars and begin your search from the Visitor Center, an open-air covered pavilion that offers outstanding views of the surrounding grasslands, as well as the southern bison unit. Be sure to pick up a hiking brochure there, for the map inside indicates the bison unit locations. Many visitors can also experience a close-up view even from their cars. Just be sure to pull off to the side of the road and turn on your hazard lights. CAUTION: When a lot of snow is present, it is difficult to find parking or a pull-off. Be safe! Also, please be considerate of Nachusa's neighbors, of their property and road use. A six-foot fence surrounds the bison units. For visitor and bison safety, there is no admittance inside these bison units, by foot or by vehicle. Visitors must stay 100 feet from the bison at all times, even when separated by a fence. The bison look tame and gentle, but they are wild and unpredictable animals. Keep in mind that the adults weigh 1000-2000 pounds, are very agile, and can quickly turn and accelerate to 30+ miles per hour. Deer The white-tailed deer is another large mammal often seen at the preserve. Look for them to gather in the early morning or right before sunset. They can even be seen grazing near the bison herd. The deer enter and exit the bison units quite easily, either leaping over the fences or, more often, going under. The fence does not go completely to the ground, and this allows other animals to come and go. The deer tracks are very recognizable. They look like upside down hearts. Beaver Nachusa has beavers throughout the preserve, for these masters of engineering have been drawn to the restored wetland habitats. In winter the beavers are not hibernating, but are snuggled inside their well-insulated lodges. They have stashed a food cache of small twigs and branches in the mud at the bottom of their pond, and they use their lodge’s underwater entrance to access the supply throughout the winter. The water is not too cold for them, even in the coldest Illinois winters, for they have a thick and very warm winter coat. In January they may begin to mate, with their young born in springtime. While the water is frozen, the beavers are unlikely to be seen. However, evidence of their presence in the landscape certainly can, if you know where to look. If you look north from the Visitor Center you can spot the lodge in the restored wetland. It looks like a mound of sticks, with some plants growing on top. Other signs of beaver presence to look for are gnawed trees and beaver stumps.

Red Fox A fox’s fur is so warm that it has no problem curling up on the snowy ground. If its nose becomes too cold, the bushy tail wraps around and makes a great facemask. In the winter, the fox will mainly eat other mammals, such as rabbits and rodents, and of course, it won’t pass up any carrion. In Illinois mating occurs during the winter months, mainly January and February. The young will be born in an underground den in March and April. Look for fox in the prairies and along the woodland edges, and it’s best to begin your search close to sunrise or sunset, because they are mainly nocturnal. Opossum The opossum is the only marsupial species (a mammal with a pouch) native to Illinois, and also to North America. That alone makes this mammal interesting and unique. Then you see that they have an opposable toe and a nearly furless prehensile tail, used to grasp things and climb. With such a naked tail, it might be expected that they hibernate during Illinois winters, but they do not. However, they do stay in their dens during really cold weather, venturing out on warmer winter days. Since opossums are omnivores, winters at Nachusa provide a lot of small mammals to eat; they also eat a lot of road kill (and then occasionally become road kill themselves). For shelter, they may find a hollow log or use one of the stacked brush piles. Opossums are nocturnal, so they’re most likely to be seen in the early morning or before sunset. Look for opossums in Nachusa’s wooded areas near ponds and creeks, for they prefer to have a den near water. Coyote Many Nachusa volunteers have enjoyed a choir of coyote voices during the nighttime hours — yips, barks, and howls — so many communicating at once, that it is hard to tell how many are present. Coyotes are very active at Nachusa during the night, probably feasting mainly on the preserve’s rabbit population, as well as other small mammals. As with many of the other animals discussed, for the most success, look for the coyotes in the early morning hours or before sunset. Look for them running along the vehicle tracks that course through the units. As seen by the coyote footprints and scat, humans are not the only mammals that like to use these vehicle tracks. Come visit the preserve this winter and enjoy Nachusa’s wide-open spaces and special creatures. Let us know in the comment section whether you see any of these mammals. Please visit the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website for the preserve's full mammal inventory list.

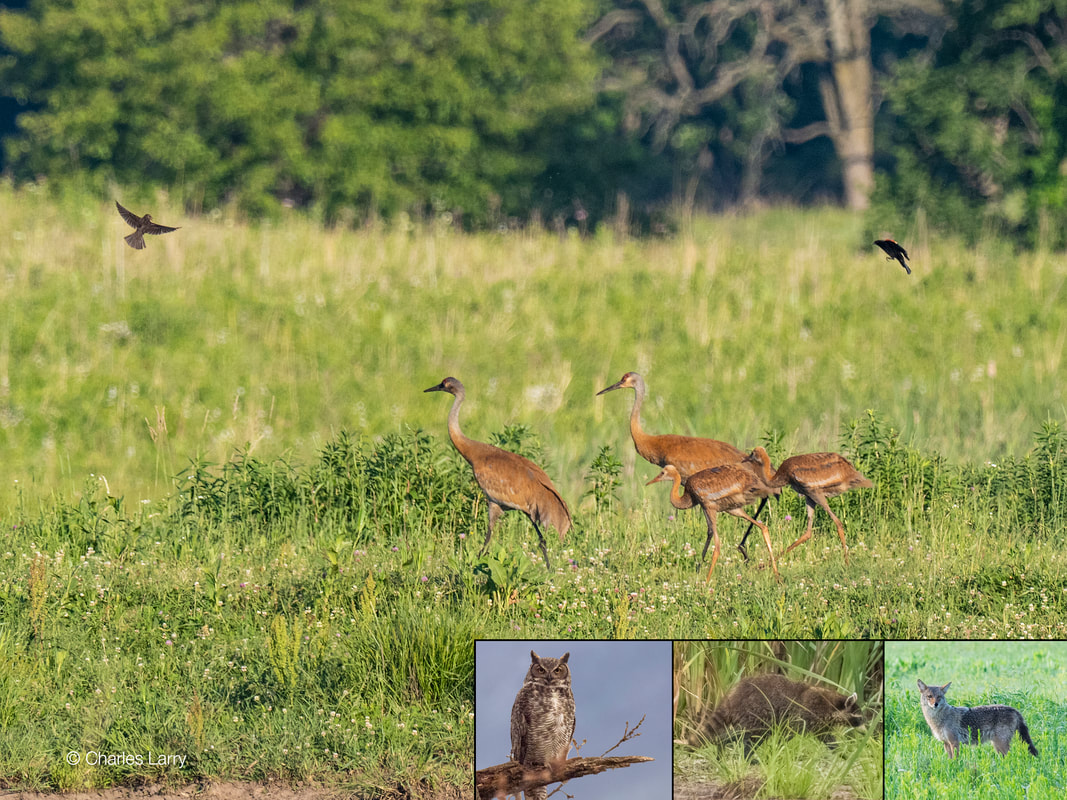

By Charles Larry Nachusa Volunteer The sound of the sandhill crane seems to echo across an immense gulf of antiquity. Cranes evolved during the Eocene (56-33.9 million years ago). The earth was warmer and wetter during this time, and in North America, with vast areas of prairie, savanna, marsh, and shallow inland seas, it was ideal habitat for the ancient ancestors of modern cranes. This early crane was likely a relative of the crowned crane now found in Africa. Fossil remains of this early crane have been found in North America, dating some 10 million years. But then the climate in North America started to cool, eventually bringing about the Ice Ages. These events saw the disappearance of this early crane on the continent. At some point a relative of the modern crane, one suited for cooler climates, evolved here. The earliest fossil of this later crane was a bone almost identical to that found in modern sandhills. This fossil was found in Florida, dating back 2.5 million years. Modern sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) are divided among two and six geographical subspecies, depending on sources. Generally, there are the greater and lesser sandhills. Nachusa Grasslands has had sandhill cranes stop over for brief periods over several years. In August of 2018, even a pair of whooping cranes stopped and then moved on! As far as is known, this is the first time that a pair of sandhills have nested and raised two colts (as the young sandhills are called) at Nachusa. It is usual for sandhill cranes to lay two eggs, a few days to a week apart, but it is rare that both colts will live to fledge. Some reasons as to why only one colt survives are various predators, lack of sufficient food, and sometimes the aggression of the older crane toward its slightly younger sibling. At Nachusa both of the young have fledged and are flying. Sandhill cranes usually mate for life. They become sexually mature at two years old but four or five years old is more likely to be when mating begins. Sandhills are well known for their "dancing" during mating season. This behavior is not fully understood, as cranes of any age may dance at times not related to breeding season. It is thought to also be a way of working off aggression. Both sexes participate in the building of the nest, constructed in or near water. Nests are composed of plant material found near the nesting site, such as cattails, sedges, rushes, and grasses. Nests can be six feet in diameter. At breeding time both sexes "paint" their feathers with clay and mud. The birds are normally gray in color, but the painting changes the feathers to brown. This is thought to be a camouflaging technique to blend in with the nesting site. Both parents incubate the eggs. While one sits on the nest, the other is either standing guard or gathering food. The female usually sits on the nest during the night. Hatching is about a month after laying. After hatching, the cranes abandon the nesting site, moving to a hidden spot somewhere still near water. The parents are fiercely protective of the young. Many predators are a danger to either the eggs or the colts. Among them are coyotes, foxes, raccoons, owls, and various hawks, all of which inhabit Nachusa Grasslands. Sandhills eat a variety of food, from insects such as grasshoppers or dragonflies, to aquatic plants and tubers, to small mammals such as mice, to snakes and worms. They will even eat the eggs of other birds, such as red-winged blackbirds, rails, and ducks. More recently, sandhills have learned to forage in cornfields and will often flock in vast numbers doing this. During breeding season, they are very territorial with an average territory range of about 20 acres. Until the cranes abandon the nesting site, where they are more or less isolated, they will defend this territory from other sandhills and predators by various aggressive displays and even fighting. By late summer the sandhills will probably move to an area where there is a larger crane population and more abundant food to fatten up for migration, which will happen sometime in the fall. The juveniles will stay with the parents during migration and through the winter. Sometime in the following spring they will separate from their parents and go out on their own. The main winter flyways for migration in this area are either south to Georgia or Florida or over to Texas. Sandhill cranes are threatened, as is true of cranes the world over. Climate change is one major threat. Droughts have become much more frequent, and wetlands are disappearing. In some states cranes are hunted. In the past, this resulted in the extinction of sandhills from Washington State in 1941. They have now been reintroduced to this state in small numbers. Farming conversion to incompatible crops (soybeans) over crops like corn also threatens cranes. Probably the biggest threat is from loss of habitat from urbanization and development. The sandhill crane is a magnificent bird. It would be tremendously sad if someday the sandhill crane were to join the thousands of species disappearing from our planet. To hear no more the sound of this bird, which author Peter Matthiessen says is "the most ancient of all birds, the oldest living bird species on earth." Sad indeed. Sources: Johnsgard, Paul A. A Chorus of Cranes: the Cranes of North America and the World. University of Colorado Press, 2015. Forsberg, Michael. On Ancient Wings. University of Nebraska Press, 2004. Matthiessen, Peter. The Birds of Heaven, North Point Press, 2001. Useful websites: If you would like to play a part in habitat restoration for sandhill cranes at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays, or give a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to support the ongoing stewardship at Nachusa.

By Jess Fliginger At first glance, it’s easy to mistake a fritillary butterfly for the well-known monarch; both can be seen fluttering across the prairie during the summer months, are similarly-sized, and are orange with black markings. In 2017 I spent the summer surveying for butterflies, particularly regal fritillaries and monarchs, in remnant prairies across the Loess Hills of Iowa. From my experience, the only way to get close enough to identify, or be fortunate to snap a photo of a butterfly is to move slowly and cautiously towards it as it’s fixed atop a flower, busily sipping nectar. Be prepared to pursue a fidgety butterfly for several yards as it swiftly drifts from one flower to the next. It took a great deal of practice and patience before I was able to become a stealthy butterfly ninja. Upon closer observation, the difference between a monarch and a fritillary butterfly becomes more apparent. There are 14 species of greater fritillaries (genus Speyeria) and 16 species of lesser fritillaries (genus Boloria). Both have a widespread range and can be found across the northern half of the United States into Canada, in some southern states, and parts of Mexico. Greater fritillaries inhabit woodland openings, meadows, prairies, and other open habitats where violets are present, while lesser fritillaries primarily live in wet meadows and bogs. Although greater fritillaries are much larger than lesser fritillaries, it can still be difficult to tell them apart while in flight. In total, there are 6 species of fritillaries that call Nachusa Grasslands home: great spangled fritillary (Speyeria cybele), regal fritillary (Speyeria idalia), aphrodite fritillary (Speyeria aphrodite), silver-bordered fritillary (Boloria selene), meadow fritillary (Boloria bellona), and variegated fritillary (Euptoieta claudia). The most common, and easiest to approach, is the great spangled fritillary. Of these, the regal fritillary is the only state-threatened species. A prairie-specialist species, regal fritillaries have drastically diminished throughout the Midwest, with only two localized populations remaining east of Illinois and several small isolated populations east of the Great Plains states and western Missouri. Typically, fritillaries have one brood and one flight period from June to August. Females lay their eggs near violets (Viola spp.), the caterpillar’s main food plant, in shady areas on the underside of dead vegetation. Soon after, the larvae hatch, crawl into nearby leaf litter, and sleep through the winter without feeding. During late winter to spring, the caterpillars begin munching on newly-sprouted violets and mature rapidly. Once fully grown, they pupate for several weeks until an adult fritillary butterfly emerges. Clearly, without violets there would be no fritillaries! Luckily for fritillaries, Nachusa has 7 species of violets throughout the preserve, as well as plenty of nectar sources to choose from. Equally as important to their survival, adult fritillaries require a large variety of nectar sources from native and non-native plants. I usually see them on coneflowers, goldenrods, ironweed, blazing-stars, milkweeds, mints, clovers, thistles – just to name a few. Plant any of these, along with violets, in your butterfly garden, and maybe a beautiful fritillary will pay you a visit. Jess Fliginger worked for Nachusa as a restoration technician during the summer of 2016. She has continued to be involved at the preserve, helping researchers conduct fieldwork and gather data. Working alongside Dr. Rich King in 2018 and 2019, she has collected data on Nachusa’s Blanding’s turtles . In addition, she has been volunteering with small mammal research since 2015, and worked for Dr. Holly Jones as a small mammal field technician in 2019. Lately, she has worked and volunteered in land restoration to enhance her skill set. She plans on assisting with prescribed burns at Nachusa this upcoming spring.

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry Spring Summer Autumn Winter

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed