|

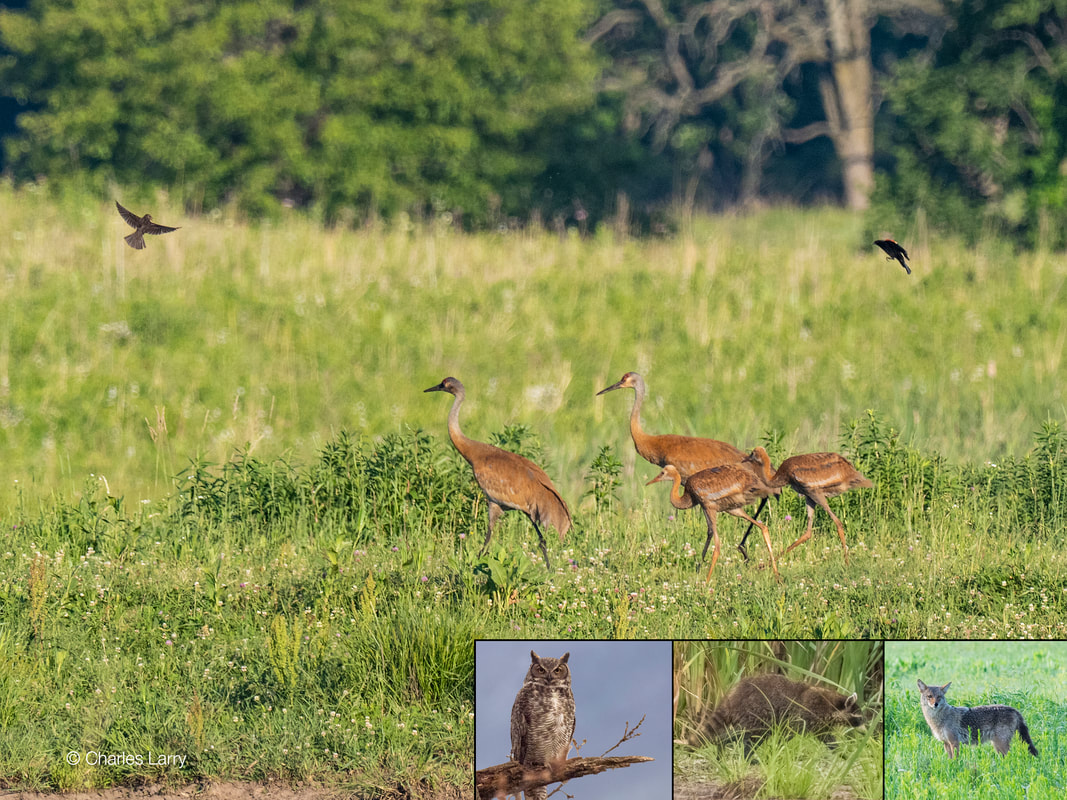

By Charles Larry Nachusa Volunteer The sound of the sandhill crane seems to echo across an immense gulf of antiquity. Cranes evolved during the Eocene (56-33.9 million years ago). The earth was warmer and wetter during this time, and in North America, with vast areas of prairie, savanna, marsh, and shallow inland seas, it was ideal habitat for the ancient ancestors of modern cranes. This early crane was likely a relative of the crowned crane now found in Africa. Fossil remains of this early crane have been found in North America, dating some 10 million years. But then the climate in North America started to cool, eventually bringing about the Ice Ages. These events saw the disappearance of this early crane on the continent. At some point a relative of the modern crane, one suited for cooler climates, evolved here. The earliest fossil of this later crane was a bone almost identical to that found in modern sandhills. This fossil was found in Florida, dating back 2.5 million years. Modern sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) are divided among two and six geographical subspecies, depending on sources. Generally, there are the greater and lesser sandhills. Nachusa Grasslands has had sandhill cranes stop over for brief periods over several years. In August of 2018, even a pair of whooping cranes stopped and then moved on! As far as is known, this is the first time that a pair of sandhills have nested and raised two colts (as the young sandhills are called) at Nachusa. It is usual for sandhill cranes to lay two eggs, a few days to a week apart, but it is rare that both colts will live to fledge. Some reasons as to why only one colt survives are various predators, lack of sufficient food, and sometimes the aggression of the older crane toward its slightly younger sibling. At Nachusa both of the young have fledged and are flying. Sandhill cranes usually mate for life. They become sexually mature at two years old but four or five years old is more likely to be when mating begins. Sandhills are well known for their "dancing" during mating season. This behavior is not fully understood, as cranes of any age may dance at times not related to breeding season. It is thought to also be a way of working off aggression. Both sexes participate in the building of the nest, constructed in or near water. Nests are composed of plant material found near the nesting site, such as cattails, sedges, rushes, and grasses. Nests can be six feet in diameter. At breeding time both sexes "paint" their feathers with clay and mud. The birds are normally gray in color, but the painting changes the feathers to brown. This is thought to be a camouflaging technique to blend in with the nesting site. Both parents incubate the eggs. While one sits on the nest, the other is either standing guard or gathering food. The female usually sits on the nest during the night. Hatching is about a month after laying. After hatching, the cranes abandon the nesting site, moving to a hidden spot somewhere still near water. The parents are fiercely protective of the young. Many predators are a danger to either the eggs or the colts. Among them are coyotes, foxes, raccoons, owls, and various hawks, all of which inhabit Nachusa Grasslands. Sandhills eat a variety of food, from insects such as grasshoppers or dragonflies, to aquatic plants and tubers, to small mammals such as mice, to snakes and worms. They will even eat the eggs of other birds, such as red-winged blackbirds, rails, and ducks. More recently, sandhills have learned to forage in cornfields and will often flock in vast numbers doing this. During breeding season, they are very territorial with an average territory range of about 20 acres. Until the cranes abandon the nesting site, where they are more or less isolated, they will defend this territory from other sandhills and predators by various aggressive displays and even fighting. By late summer the sandhills will probably move to an area where there is a larger crane population and more abundant food to fatten up for migration, which will happen sometime in the fall. The juveniles will stay with the parents during migration and through the winter. Sometime in the following spring they will separate from their parents and go out on their own. The main winter flyways for migration in this area are either south to Georgia or Florida or over to Texas. Sandhill cranes are threatened, as is true of cranes the world over. Climate change is one major threat. Droughts have become much more frequent, and wetlands are disappearing. In some states cranes are hunted. In the past, this resulted in the extinction of sandhills from Washington State in 1941. They have now been reintroduced to this state in small numbers. Farming conversion to incompatible crops (soybeans) over crops like corn also threatens cranes. Probably the biggest threat is from loss of habitat from urbanization and development. The sandhill crane is a magnificent bird. It would be tremendously sad if someday the sandhill crane were to join the thousands of species disappearing from our planet. To hear no more the sound of this bird, which author Peter Matthiessen says is "the most ancient of all birds, the oldest living bird species on earth." Sad indeed. Sources: Johnsgard, Paul A. A Chorus of Cranes: the Cranes of North America and the World. University of Colorado Press, 2015. Forsberg, Michael. On Ancient Wings. University of Nebraska Press, 2004. Matthiessen, Peter. The Birds of Heaven, North Point Press, 2001. Useful websites: If you would like to play a part in habitat restoration for sandhill cranes at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays, or give a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to support the ongoing stewardship at Nachusa.

12 Comments

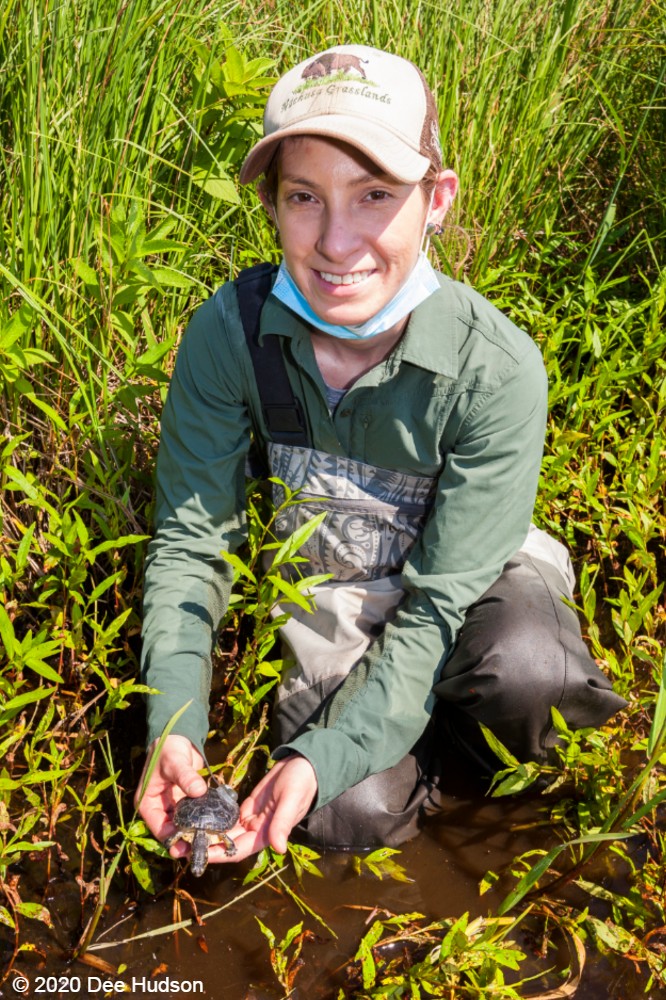

By Jessica Fliginger Blanding's Turtle Field Technician  State-endangered Blanding's turtles call the wetlands of Nachusa Grasslands home. Head-starting programs hope to combat juvenile mortality and give young turtles a better chance of survival. Sprawled out in the palm of my hand, the fidgeting turtle eagerly stares at the glistening water ahead. I lower my hand to the surface water and can feel its tiny claws push off my thumb as it glides away. The turtle stops briefly to poke its head out of the water and scan its surroundings before vanishing into the sedges. The Blanding’s turtle, a long-lived, late maturing, semi-aquatic turtle, is a declining species in dire need of conservation efforts. Endangered in Illinois, Blanding’s face a multitude of threats including habitat loss and fragmentation, nest and hatchling depredation, road mortality, and commercial collecting. To learn more about the threats to Blanding’s turtles in Illinois, check out my previous blog post. Low juvenile survival, the main driver of population declines, has prompted many conservation agencies to intervene through head-starting programs, in order to provide protection for vulnerable hatchlings. In 2019, managers at Nachusa Grasslands and Richardson Wildlife Foundation initiated a joint head-starting program for endangered Blanding’s turtles in cooperation with the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County (FPDDC) and the Lake County Forest Preserve District (LCFPD). As a result, more than 70 one year-old Blanding’s turtles were released into native prairie habitat at Nachusa Grasslands and Richardson Wildlife Foundation. At each site, 37 head-starts were released, 20 with transmitters and 17 without. By equipping turtles with custom-built transmitters, scientists at NIU will be able to track and monitor their movements, growth, and survival — key information for a conservation-reliant species. Data collected will inform managers on critical areas for the turtles, in addition to what predators are present and the impacts they have on hatchling survival. As we have discovered, there are many components to developing and implementing a management plan for the Blanding’s turtle population at Nachusa, and measuring its success will be a long-term commitment.  Equipped with a radio transmitter, a young Blanding's turtle is released into the water. This turtle will be tracked and measured to monitor its survival in the wild. The Blanding’s turtle head-starting program involves annual egg recovery from nests, incubation, and captive rearing of hatchlings. After assisting Dr. Richard King during nesting season for four years, I can say that catching a female in the act of laying its eggs is not an easy task. I’ve learned that every nest counts, especially because there are so few adult female turtles, and their clutch sizes are so small. Last year, Dr. King and I successfully tracked all females to their nesting sites and collected 41 eggs! Upon recovery, these eggs were transported to the FPDDC, where they were incubated. Since Blanding’s turtle sexes are determined by temperature, females were incubated at 30°C and males at 26°C. Once hatched, the LCFPD captive-reared the turtles for a year until they were released this June. After the 20 head-start turtles were released, I began tracking them using radio-telemetry three times per week. Although locating the small turtles has its challenges, I have grown to enjoy it. I collect data on GPS location, environmental variables (e.g. muck and water depth), and any notes on behavior if I can get a visual on them. The majority of the time the turtles are in the water, staying cool in the muck or trying to evade my presence by swimming away. On good days I will find them basking on logs or near the edge of the water. They are extremely skilled at camouflage, as their shells blend in with their surroundings. Every two weeks I physically locate each turtle to take measurements and confirm survival. Finding the turtles can turn into quite the ordeal; once I had to stick my arm down a crayfish burrow to pull a turtle out. It mostly involves digging through the mucky water and sifting through sedge root masses until I feel something hard. When I finally find the turtle, I weigh it (in grams) using a small scale and use calipers to take measurements (in mm) of its shell. I take measurements on carapace (upper shell) length, carapace width, plastron (bottom shell) length, and shell height. They usually flail their arms and legs as I take measurements, trying to pry away my calipers with their tiny claws. Although the turtles struggle, they have never attempted to bite me (unlike snakes, mice, and snapping turtles), making them the most pleasant animals to process.  A released head-started turtle has its shell height measured, flailing its legs through the process. Digital calipers are a helpful tool when measuring wiggly turtles. This year, we managed to collect seventeen eggs for head-starting — a lot fewer than the previous year. Losing two of our adult females from 2019, in addition to several sneaky females nesting undetected despite regular checks, has impacted the number of eggs we were able to collect. In the future, we hope to locate new adult females so we can supplement the number of eggs admitted to our head-starting program. It has taken many years to accomplish our goal of a head-starting program and would not have been possible without support from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands, Nachusa staff, NIU Biological Sciences Department, Forest Preserve District of Dupage County, and Lake County Forest Preserve District. Results from research on the head-starts will help guide future management plans for Blanding’s turtle populations at Nachusa and Richardson Wildlife Foundation. I’ve had a lot of fun tracking the Blanding’s turtles at Nachusa and it has made me appreciate what an incredible species they are. Blanding’s turtles are one of reasons why Nachusa Grasslands is such a special place.  Some members of the next class of head-started Blanding's turtles. Though numbers of eggs were lower this year, the program will carry on! Dr. Richard King's ongoing research on Nachusa's Blanding’s turtle management strategies is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. If you would like to play a part in helping the turtles at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. Jess Fliginger worked for Nachusa as a restoration technician during the summer of 2016. She has continued to be involved at the preserve, helping researchers conduct fieldwork and gather data. Working alongside Dr. Rich King as a volunteer in 2016 and a field technician for the past three years, she has collected data on Nachusa’s Blanding’s turtles. In addition, she has been volunteering with small mammal research since 2015, and worked for Dr. Holly Jones as a small mammal field technician in 2019. Currently, she is monitoring the first-year Blanding's head-start turtles at Nachusa.

By Dee Hudson and Charles Larry Spring Summer Autumn Winter

By Jessica Fliginger Today, half of the world’s freshwater turtles and tortoises are threatened with extinction. Due to the alarming rate of turtle disappearance, they are now among the most threatened group of vertebrate animals on earth. Turtles play critical roles in maintaining the health of our food webs and losing them could have negative effects on our ecosystems. In Illinois, Blanding’s turtles are listed as state endangered, making it illegal to possess or collect this species without the proper permit. Populations are in decline throughout their range, which extends from Canada and Novia Scotia, south into New England, and west through the Great Lakes to Nebraska, Iowa, and northeastern Missouri. In general, their populations are small, discontinuous, and often isolated. Blanding’s are long-lived turtles and can live up to 80 years. Females don’t reach sexual maturity until 14 to 20 years and have small clutch sizes ranging anywhere from 5 to 20 eggs. Based on this information, I’m sure you can gather that Blanding’s turtles, like most turtles, face a multitude of challenges in our human-dominated landscape where there are plenty of predators to avoid. It’s extremely hard to have a bad day out on the prairie when I’m using radio telemetry to track Blanding’s turtles at Nachusa Grasslands. The "smile" they exude reflects their behavior; they are pleasant to handle and not at all aggressive, unlike snapping turtles I’ve encountered. I have been fortunate to spend the past two years working as a Blanding’s turtle field technician for Professor Dr. Rich King in the Department of Biological Sciences at Northern Illinois University. In an effort to promote recovery of the state-endangered species, he has been using radio telemetry as a tool to better understand which areas the turtles are utilizing so they can be protected and management plans to improve their habitat can be implemented. Additionally, radio telemetry can be used to improve Blanding’s turtle hatchling recruitment. If you’ve ever tracked any animal you understand what I mean when I say, “Easier said than done!” Finding a turtle on a mission to lay her eggs is hard enough, but trying to predict if and when she will lay her eggs seems like an impossible task. Although it’s a lot of hard work, Dr. King and I have pretty much figured it out. After we have taken our data, the hatchlings are released back into the wetlands near their nest sites. In order to increase their chance of survival out in the wild, it has become necessary for us to assist the Blanding’s turtle population. It may take several field seasons of tracking them at Nachusa before we can get a full understanding of how they are using the area or if there are any other individuals present. For the time being, what’s important is that we are monitoring their movements, protecting critical habitat, and sparing the hatchlings the overland journey of getting to the wetlands.

Blanding’s turtle eggs are particularly vulnerable to nest predators such as raccoons, skunks, opossums, foxes, mink, and coyotes. High nest failure means low recruitment level and if juveniles are not surviving then that’s when a population begins to decline. Moreover, roads located near wetland habitat, movement corridors, and nesting areas increase risk of mortality for Blanding’s turtles. It’s always a good idea to keep a lookout for turtles crossing the road. I know if I see a turtle in the middle of the road, given the opportunity, I will pull over and move them out of harm’s way! You never know, it could be a state-endangered Blanding’s turtle. As an undergraduate, I grew fascinated with Blanding’s turtles after seeing one for the first time on a biology field trip and I’ve always wanted to find a way to help them. Little did I know I would get to do just that! Dr. Richard King's ongoing research on Nachusa's Blanding’s turtle management strategies is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands.

If you would like to play a part in helping the turtles at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. Ephemeral ponds are temporary ponds of springtime, sometimes called vernal pools. Springtime, melting snow, and spring rains bring water and life to the ephemeral ponds and vernal pools at Nachusa Grasslands. Amphibians and macro invertebrates use these ponds as a nursery for their young. These small bodies of water flourish in the spring and then quietly, without notice, disappear into the heat of the summer. While they exist, they offer special advantages and challenges for the life that inhabits them. Plants and animals in ephemeral pools must be adapted to wet conditions in spring and dry conditions by early summer. Plants that thrive in vernal ponds are very often the same plants that one would find on the edge of permanent ponds. Permanent ponds overflow their banks in spring and a shoreline of sedges, grasses, and forbs begin to emerge in the cold water. These same types of plants emerge in the cold water of vernal pools. These plants will continue to thrive on the shores of a permanent pond as the water recedes and in vernal pools as the water fades and the pond dries. Frogs and salamanders seek out ephemeral ponds as safe breeding pools and nurseries for their young. A pond that dries out part of the year, or freezes entirely, prevents fish from establishing. Fish would eat amphibian eggs, small tadpoles, or small sallywogs*; they would also compete for the macro invertebrates that provide a rich source of food for the adult and juvenile amphibians. The trade-off is the young must grow fast enough to leave the pool before it dries in the summer heat. Nachusa’s ephemeral ponds have the advantage of being surrounded by a rich and diverse grassland. As the ponds dry, the young that managed to mature enough to leave the watery place of their youth, can venture forward into a land of plenty. Appetite-satisfying insects are plentiful. The tall grasses and abundant flowering plants provide camouflage and shelter. This is a sharp contrast to ponds among row crops, where the plants are a monoculture and are frequently sprayed with pesticide. Or, in the suburbs, where lawns are mowed right up to the waters edge, leaving no place to hide; tasty insects are sparse. Many times ephemeral ponds are filled, drained, or dug deeper to create a permanent pond, ruining the qualities that support unique macro-invertebrate and amphibian life. At Nachusa the challenges of survival in the natural world exist for amphibians, but without many of the artificial challenges that the modern world brings. Nachusa has many of these wonderful ephemeral ponds. They can often be located this time of year by the sounds of calling frogs. Western chorus frogs and spring peepers are the first to begin calling in late March or early April and are later joined by northern leopard frogs and American toads. Readers of the blog are likely familiar with the sound of the western chorus frog, often described as the sound of a fingernail being dragged across the teeth of a plastic comb; or its contemporary the spring peeper whose call begins with peep, peep, peep. The trill of the American toad is long and carries in the night air. The northern leopard frog with its low rumble, is followed by a bit of chuckle. The copes gray treefrog begins calling around early May; its call is a similar trill to the American toad, but instead of a long steady call, the copes trill comes in quick, short bursts often two or three at a time. Listen for calling frogs after the sun sets, when the winds are calm. One resident of Nachusa is never heard and seldom seen. The silent, but intriguing tiger salamander with its marbled skin, likely visits these ponds as a refuge and breeding site. Presently the pond waters are filled with eggs of frogs and salamanders. Soon these vernal pools will be filled with tadpoles and sallywogs* competing to be the next generation of amphibian life at Nachusa. As volunteers and staff at Nachusa restore the native landscape, ephemeral-pond-dependent species grow in population and diversity. Drain tiles throughout the preserve have been broken or removed, and low spots have been enhanced to return the natural hydrology to the land and allow spring wet areas to return; this increases the areas for amphibian populations to expand. It has been reported that the call of the plains leopard frog has recently been heard near the Tellabs ponds. If confirmed, another species can be added to the list of animals that call Nachusa home. The ephemeral ponds surrounded by plentiful grasslands preserves the ecological diversity that is the living tapestry of Nachusa Grasslands. Text and Photos by Paul Swanson

*Sallywogs used to denote salamander larvae vs. frog larvae. |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed