|

By Kirk Hallowell and Mary Meier Nachusa Grasslands Volunteers Each year, volunteers commit over 8,000 hours of service to the restoration efforts of Nachusa Grasslands. Volunteers harvest seeds, keep invasive species at bay, assist in scientific research, tend prescribed fires, and perform a myriad of other tasks essential to the restoration process. Volunteer projects must be supported by equipment, herbicide, contract services, and other resources needed for success. Fortunately, the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation empowers volunteers by providing grant funds as a match to local dollars raised and labor donated. Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program awards are used to purchase equipment, herbicide, and services necessary to make these volunteer activities possible. According to its website, “ The Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation (ICECF) was established in December 1999 as an independent foundation with a $225 million endowment provided by Commonwealth Edison. Our mission is to improve energy efficiency, advance the development and use of renewable energy resources, and protect natural areas and wildlife habitat in communities all across Illinois.” (@illnoiscleanenergycommunityfoundation) The Illinois Community Foundation will award Friends of Nachusa Grasslands a grant of up to $30,000 if we fulfill requirements under several categories between May 1, 2023, and April 30, 2024:

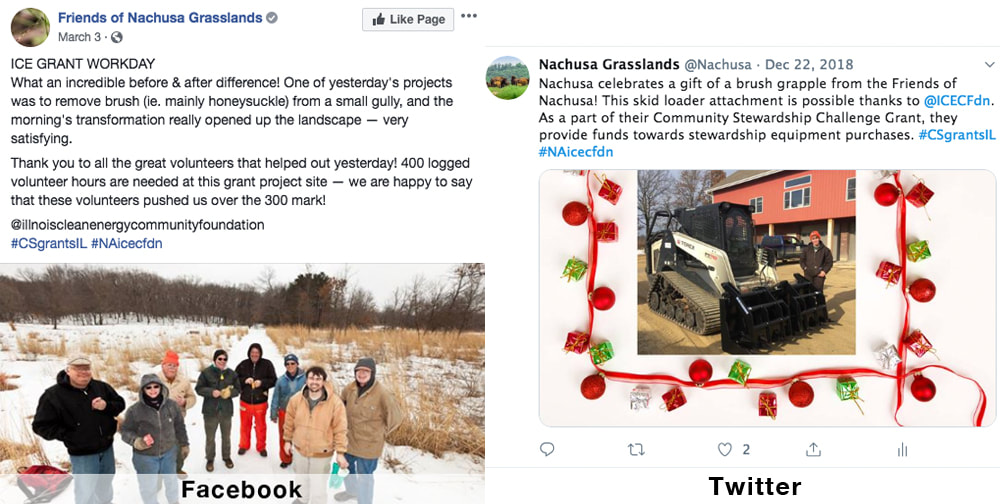

Under the leadership of project coordinator, Kirk Hallowell, Friends has chosen two sites at which to focus volunteer hours and grant resources for their current stewardship project: Nachusa’s Big Jump Unit and the Holland Savanna Unit. Both areas are infested with invasive shrubs, including autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) and amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), two of the most tenacious foes that Nachusa’s volunteers battle. On its "Where We Work" web page, The Nature Conservancy explains, “Autumn olive is a problem because it outcompetes and displaces native plants. It does this by shading them out and by changing the chemistry of the soil around it, a process called allelopathy. Loss of native vegetation can have cascading effects throughout an ecosystem, and invasive species are one of the major drivers for a loss of biodiversity.” According to a Friends of Nachusa Grasslands blog post by Scientific Research Grant recipient Kaleb Baker, “Amur honeysuckle is an invasive shrub that flourishes along forest edges and in open woodlands such as those at Nachusa Grasslands. Amur honeysuckle shades out native flora with its early leaf-out and prolonged leaf retention, and when left uncontrolled, it can produce a near monoculture, threatening biodiversity.” Some of the ICECF funds already awarded have been invested in herbicide effective in eradicating autumn olive and amur honeysuckle. Volunteers treat the plants using backpacks and handheld sprayers. The next facet of the Big Jump project is to cut down and stack hundreds of non-native trees to make room for prairie restoration. This task that requires heavy equipment owned and operated by an external tree service contractor. ICECF grant funds will also be used to pay for the machinery and professional tree fellers. Kirk, who also serves as steward of the Holland Unit, offered, “It is exciting to know that the efforts of our volunteers empowered by the ICECF grant resources will make a lasting impact on our efforts to control amur honeysuckle in the Holland Savanna.” An additional challenge for the Holland Unit is that the parcel is dominated by cool weather grasses, including rye and fescue, which are typically resistant to overseeding efforts to establish native prairie plantings. In the second half of the ICECF grant period, we will experiment with preparation methods using herbicide to loosen the grip of the dominant grasses and allow overseeding of native plants to take hold. During the fall months, volunteers also helped collect seeds from the preserve for enhancing our prairie plantings. Our long-term goal is to establish a diverse prairie planting on both the Big Jump and Holland Savanna sites providing for long-term weed management and suppression of non-native shrubs and trees. Ongoing stewardship efforts, including volunteer labor, herbicide application, and controlled burns, will gradually help integrate the target areas into the surrounding habitat. The Friends Social Media Team uses Facebook, Twitter/X, Instagram, and our website to promote volunteer opportunities. You can also follow Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation’s Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program on Facebook and Twitter/X to learn more about the Foundation. #CSgrantsIL #NAicecfdn How Can You Help Friends Earn the ICECF Stewardship Grant?

Volunteer for a Thursday or Saturday brush clearing workday — check SignUpGenius for the schedule. Meet at Nachusa’s Headquarters Barn before 10 am and be ready to restore habitat. If you have any questions about the workdays, check the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website.

0 Comments

By Josh Klostermann Doctoral Student, Department of Plant Science and Technology at the University of Missouri Have you ever observed a bee tenaciously collect every grain of pollen out of an anther and then zoom off into nothingness? Where did that bee go? An easy answer to that question is back to its nest, but the nesting habits of most bees are mysterious. Where each different species decides to build a nest is poorly understood and not frequently observed. So, it may be more difficult to locate that pollen-loaded buzzer than originally expected. It is at the intersection of this problem and Nachusa Grasslands where my passion for a good hunt, infatuation with natural history observation, and the regionally uncommon bee Anthophora abrupta collide. But first I will give a little backstory. Most bees are solitary, and most bees that are solitary are soil excavators. In other words, a large majority of the bees on this planet live alone (without a hive or queen) and dig underground to build their nests. Where a solitary mother bee chooses to build her nest is arguably one of the most important decisions she will make in her life. There is an immense pressure on her to be able to pick a nesting site that will allow her to operate as efficiently as possible while also reducing the risk of nest failure through predation, parasitism, or infection from pathogens. Once committed to a nesting site she will invest all her energy on that place, visually and chemically remembering where it is, provisioning the cells she creates with hard foraged pollen, and laying eggs on those provisions to ensure that more of her kind will emerge the following year. With these responsibilities, it may be safe to assume that bees must be keen on detecting differences in above and below ground microhabitats in order to choose a site that will allow them to be as fecund as possible in their short lifetimes. Some examples of microhabitat differences that would be relevant to a nest founding bee may be the amount of bare ground at a site, the amount of sunlight the site receives, and the texture and compaction of the soil. The degree to which these differences in microhabitats filter what can exist in a community is largely unknown and an important puzzle piece in understanding how bee species persist. As a researcher, I am focused on how the presence of these microhabitats affect what bees and wasps nest where in a landscape and how disturbances alter the landscape to create many different types of microhabitats for bee and wasp nests. Disturbance is an unavoidable reality in ecology. It is often painted in bad light due to our human ability to disturb so profoundly that it alters communities indefinitely, but not all disturbance is bad. In fact, small scale disturbance at intermediate intervals has been shown to increase the diversity of organisms in an environment and promote co-existence. Therefore, identifying mechanisms of small-scale disturbance that provide this sort of stability to bee and wasp communities is essential to their conservation. One mechanism of disturbance I am becoming increasingly interested in is wind. When a mature tree is downed by wind, several different things happen at a microhabitat scale. First of all, the root system is uplifted and a pit of exposed ground with an associated vertical wall of a soil-root matrix is created. These soils are fundamentally different from the surrounding soil just by the nature of being covered and ensconced in tree roots for decades and then one day suddenly uplifted. Also, canopy cover decreases, and there is an influx of light into the immediate area adjacent to the downed tree. This creates temperature and moisture differences from the surrounding woodland. The disturbance of a freshly-downed tree creates an array of free “real estate” that a bee or wasp may find suitable as a nesting site. This real estate is a hot commodity, and downed mature trees are rare in today’s forests. As time moves on, more trees become downed, and the bees and wasps that utilize these spaces disperse to fresh sites. I believe that this sort of dynamic, small-scale, and intermediate disturbance may be a crucial component to the stability of bee and wasp populations that nest in woodlands. In the summer of 2021, I scoured the wooded areas of Nachusa grasslands and surrounding forests looking for these “tipped-up” microsites. By targeting these places, I have been able to confirm that they are indeed being utilized as nest sites for several different species of bees and wasps. An important discovery was finding Anthophora abrupta at three different sites in Northern Illinois all nesting in the soil-root matrix of “tip-ups”. This bumblebee look-alike is regionally uncommon and was a site record for Nachusa Grasslands. While carefully observing the nesting sites of A. abrupta I was also able to spot their associated cleptoparasite; Brachymelecta californica. A cleptoparasite is an organism that steals resources from another. B. californica will search for nests of A. abrupta, sneak inside, and lay its eggs on the pollen provisions collected by their host. This bee is extremely rare to the region and was a first record for the state of Illinois. Other notable members of the “tip up” community thus far are Myrmosa unicolor, Philanthus gibbosus, Pseudomethoca frigida, and small metallic sweat bees in the Lasioglossum subgenus Dialictus. There is so much more to bees and wasps than flowers and stinging. I hope that this blog post has opened a new window for looking at these small insects with curiosity and wonder. It is through careful observation and patience that insight may be passed from the non-human to the human. The actions of an invertebrate may seem insignificant, but these organisms have been surviving on earth for much longer than us. Next time you’re in the prairie in the sweltering humidity of midsummer and the droning of bees swerving between pink rays and into white corollas feels disorganized, even chaotic, take a swig of water, a bite of lunch, and a closer look: those supersonic meanders may begin to look like slow dances with each bee’s movements holding purpose.

Friends of Nachusa Grasslands awarded Josh Klostermann Scientific Research Grants in 2022 and 2023. Are you interested in supporting research projects at Nachusa? Just designate your Donation to "Scientific Research Grants."

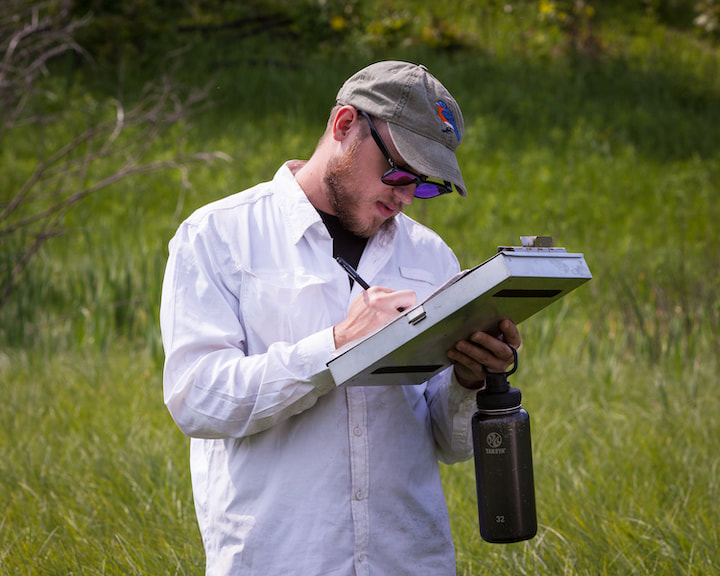

By Luke D. Fannin PhD Candidate, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH Grass-eating, or graminivory, as it is called by scientists, is a strange behavior. At the outset, grasses, at least compared to the many plant foods that humans consume regularly, look unappetizing; they are tough to chew, they are full of fibers that make them difficult to digest, and they are often covered in dust and sand from growing close to the soil surface. But for many mammals, ranging in size from tiny voles (20-24 grams) all the way up to gigantic white rhinoceroses (2400 kilograms), grasses are dietary staples, and these so-called “grazers” (grass-eating mammals) are pivotal in Earth ecosystems. Nachusa Grasslands is home to one of North America’s most important grazing mammals, the bison (Bison bison), which eats grasses in most months of the year. But if grasses are such difficult foods to eat, how do bison–let alone any other mammals–eat them? As it turns out, bison have a few tricks up their proverbial sleeves as it pertains to eating grasses. For starters, bison are ruminant mammals, which means they have highly specialized stomachs that allow them the ability to regurgitate and then re-chew partially digested plant foods. Think of how a domestic cow eats; the cow first swallows a bite of food but then proceeds to regurgitate that bite of food and chew it again, and again, and again… until finally those food particles are small enough to pass through the rest of the digestive system. With each subsequent swallow, foods are bathed in stomach juices teeming with bacteria, which also help to weaken the structural integrity of fibrous foods and liberate nutrients. This digestive trick is incredibly helpful for bison, as it allows them to digest grasses in a way that humans cannot. Secondly, bison are endowed with highly specialized teeth, termed hypsodonty. Unlike the surfaces of our own teeth, which fully poke out of our gums when they erupt, bison’s teeth emerge in a piecemeal fashion over the course of their lives, meaning that they usually have more teeth hiding within their skulls at any given point in time. A good analogy for how bison teeth work is the lead found in the tip of a mechanical pencil: while there is always lead at the pencil tip exposed for writing, there is far more lead stored within the pencil that emerges to eventually replace the used-up lead after writing is finished. Hypsodonty is thus a useful trait for Nachusa bison because most grass plants are also abrasive (see below), meaning they remove tooth surface, or enamel, during chewing. Hypsodonty allows bison to continuously provide new replacement tooth surface over the course of their lives, allowing them to keep eating grass plants without having to worry about completely losing their teeth in the process (although they are not actively growing teeth, and this excess amount of tooth eventually wears out in old age).  Bison teeth are hypsodont, meaning that the dental crowns are tall and most of this length is stored within the bones of the face and jaw. This trait provides a hidden reservoir of tooth material that can be pushed out when the surfaces of the teeth wear, allowing for tooth function to be preserved in the face of extremely abrasive conditions. In addition, when bison teeth wear, the enamel forms elaborate cutting surfaces with a harder underlying tooth material (referred to as dentin, which is the brown material contrasted against the pearly-white enamel on the tooth surfaces). These elaborate cutting surfaces help bison mince plant foods. But with all this talk of bison traits to eating grass, it is easy to view the grasses themselves as passive players in this story of herbivory at Nachusa. But can grasses fight back? My own work at Nachusa Grasslands seeks to answer this question with one plant trait that may act as a defense against herbivory . . . silica levels. While we often think of silica as being a component of our modern technology (e.g., in computer chips), silica is also one of the most abundant minerals in Earth’s soils. Grasses, in turn, uptake silica into their own tissues during growth, where it usually gets deposited into silica bodies called phytoliths. The function of silica accumulation in grasses is debated, but one thought is that it provides a defense against defoliation (i.e., the removal of leaves). As suggested previously, grass plants are abrasive, and it is the silica in grass leaves that hypothetically works to remove enamel. As such, high levels of silica in grass leaves may deter mammalian consumers from eating them — for risk of damaging their teeth — helping to prevent defoliation. Silica also works to stiffen plant leaves, making them more difficult to chew and digest, while also further inhibiting microbial digestion in the digestive tract. Thus, silica be an inducible defense for grasses, wherein a re-growing grass plant responds to previous herbivory by increasing silica uptake to prevent severe defoliation in the future. But silica has other important functions in grass plants that are unrelated to herbivory. For example, increased silica uptake in grasses is also important for relieving environment stresses related to both high temperatures and low water availability. Therefore, it remains challenging to determine whether the high silica levels found in some prairie grass plants are primarily a response to intense herbivory pressure (i.e., from roaming bison) or are instead a plastic response related to changes in local environmental conditions that may increase growing stresses.  Bison at Nachusa can exhibit immense herbivory pressure on the local grassland community and repeat herbivory at certain locations can create what are termed “grazing lawns”, where grass plants are maintained in a short-statured state as compared to surrounding vegetation. It remains unknown whether the grass species within these “grazing lawns” at Nachusa possess higher silica levels in their tissues than similar species within exclusion plots, but previous work on the African Serengeti has suggested that grasses in such features are more silica-rich than similar species under less extreme herbivore pressure. My current work at Nachusa Grasslands seeks to shed light on this mystery. By taking advantage of bison exclusion plots set up across the lands of the reserve, I can compare the silica levels of different grass species (and other related traits, such as photosynthetic pathways, leaf toughness, and nutrient levels) in locations where they have experienced almost a decade of bison herbivory (2014 – 2021) to those same species in exclusion areas where bison herbivory has been much less intense or non-existent. My hope for my continuing work at Nachusa is to disentangle the various factors that may influence silica levels in various grass tissues of prairie plants and, by extension, in the diets of Nachusa bison. My overarching goal is to figure out if re-introduced bison are helping to change the functional traits of grasses growing within the Nachusa reserve, and if so, what this might mean for plant community structure and resilience moving forward.  Exclosure or herbivore exclusion plots are key to testing hypotheses regarding inducible plant defenses and bison herbivory at Nachusa Grasslands. The bison have access to the plants on the left side of the photo, but in the right side of the photo begins the exclosure, a space that is completely isolated by fencing and the bison cannot enter. Notice the taller vegetation in the exclosure. Numerous exclosures are found throughout the bison unit.  The author (L.D. Fannin) in his mobile lab processing collected grass plants in the field at Nachusa in June 2021. To prevent molding, grass plants need to be dehydrated before transport, and the food dehydrator at the far right allows for the dehydration of plant remains to occur quickly before plants are then ground and stored with desiccant. The author is currently analyzing these collected plant parts for their silica content at Dartmouth.

Luke Fannin was a 2021 Scientific Research Grant recipient from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Interested in supporting Nachusa's science? Just designate your Donation to "Scientific Research Grants."

By Elizabeth Bach Research Scientist at Nachusa Grasslands, The Nature Conservancy Nachusa has experienced several ups and downs in 2021. COVID-19 continued to bring challenges and require flexibility. We celebrated the opening of our new equipment barn, but we also grieved the loss of naturalist Wayne Schennum. Wayne conducted plant and insect surveys at Nachusa throughout his long career and was actively working on a survey of leaf beetles prior to his passing this summer. Amid this uncertainty, the Nachusa science community managed to accomplish a lot.

Pete Guiden started 2021 strong with the publication of Effects of management outweigh effects of plant diversity on restored animal communities in tallgrass prairie in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This is one of the top three scientific journals in the world; it is a major accomplishment for Pete and his co-authors in the Holly Jones and Nick Barber labs. It is significant for a Nachusa dataset to contribute to global scientific advancement in this way. They found management-driven responses were more common (and stronger) than plant-driven responses. Restoration age was the main driver of management effects, followed by prescribed fire. Both plant diversity and active management were critical to restoring animal biodiversity. You can learn more from Pete’s blog post. Another significant Nachusa publication was Twenty years of tallgrass prairie restoration in northern Illinois, USA, published in Ecological Solutions and Evidence as part of a global special issue on the UN Decade on Restoration. Elizabeth Bach analyzed 20 years of plant survey data from permanent transects set up by Bill Kleiman. Plant communities on native prairie remnants have maintained or increased plant diversity, including rare plants. Savannas maintained similar levels of plant diversity, but plant communities shifted from understories dominated by brush to herbaceous plants, including native grasses and flowering plants. The special issue on the UN Decade on Restoration also featured a paper from Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar and Sean Griffin. Variation in prescribed fire and bison grazing supports multiple bee nesting groups in tallgrass prairie showed that a mixture of fire and grazing on the landscape encouraged diverse bee communities by promoting bees with different nesting habits. Nachusa bees were primarily ground-nesting (90% of observed species), but stem/hole nesters (3.6%) and large-cavity nesters (6%) are also important parts of the community. This team also published Bee communities in restored prairies are structured by landscape and management, not local floral resources in Basic & Applied Ecology. Large-landscape restorations were positive for bees, as the relationships with floral diversity observed in previous work in small, isolated prairies did not hold up at Nachusa. Several Nachusa insect studies were published in 2021. Michele Rehbein, who surveyed mosquitoes at Nachusa for her PhD work at Western Illinois University, published A new record of Uranotaenia sapphirina and Aedes japonicus in Lee and Ogle Counties, Illinois. Both these mosquitoes are new records for the area and contribute to broader understandings of mosquito communities in Illinois generally. Azeem Rhaman published Disturbance-induced trophic Niche shifts in ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in restored grasslands, summarizing his MS research with Nick Barber at San Diego State University. He found ground beetles consumed a wider range of food sources in areas with bison grazing, particularly with both grazing and fire. Meghan Garfinkel, who earned her PhD from University of Illinois – Chicago, specifically examined insects present in bird diets. Using faecal metabarcoding to examine consumption of crop pests and beneficial arthropods in communities of generalist avian insectivores, published in Ibis, was the first study to leverage next-generation DNA sequencing to analyze diets of entire bird communities. Birds consumed more herbivorous arthropods (plant-eating bugs) compared to carnivorous arthropods (bug-eating bugs). Heather Herakovich published two papers on birds this year. In Impacts of a Recent Bison Reintroduction on Grassland Bird Nests and Potential Mechanisms for These Effects, she found that bison presence did not impact nesting density or vegetation structure, but nest success increased in the first two years after reintroduction. Heather evaluated birdsong to passively survey communities in Assessing the Impacts of Prescribed Fire and Bison Disturbance on Birds Using Bioacustic Recorders. This dataset showed that having a mix of recently-burned, unburned, and grazed habitat in the landscape supported diverse bird communities, as different species have different habitat preferences. It was a strong year for animal publications from Nachusa. Rich King and graduate students Monika Kastle and Callie Golba published two papers about their work on Blanding’s turtle recovery in northern Illinois, including the Nachusa population. Blanding's Turtle Demography and Population Viability focused on modeling needs for Blanding’s turtle populations to sustain themselves. Blanding's Turtle Hatchling Survival and Movements following Natural vs. Artificial Incubation reported on the results from the 2020 release of Blanding’s head-start hatchlings at Nachusa and other sites. Survival rates were variable across the populations, and research continues at Nachusa to find the most effective ways to protect these turtles. Publications of threatened and endangered species extended to plants as well. Katie Wenzell, who earned her PhD from Northwestern/Chicago Botanic Gardens, published Incomplete reproductive isolation and low genetic differentiation despite floral divergence across varying geographic scales in Castilleja in the American Journal of Botany. This work examined the genetic relatedness and floral variability of Castelleja sessiliflora (downy paintbrush) and C. purpurea (prairie paintbrush or purple paintbrush) across their geographic ranges. Both species are evolving, but C. sessiliflora is exhibiting genetic differentiation, whereas C. purpurea is exhibiting differences in flower shape without genetic changes. These are two different mechanisms driving similar evolutionary outcomes. Timothy Bell and colleagues explored population trends in the threatened eastern prairie fringed orchid in Environmental and Management Effects on Demographic Processes in the U.S. Threatened Platanthera leucophaea (Nutt.) Lindl. (Orchidaceae). They found regular burning and wet weather lead to greater blooming populations for the orchid. To evaluate landscape-level plant community and soil characteristics, Ryan Blackburn tested aerial imaging from drones in Monitoring ecological characteristics of a tallgrass prairie using an unmanned aerial vehicle, published in Restoration Ecology. Drone images did an adequate job of evaluating grass cover and mean dead plant cover, but more work is needed to refine this method. Scientific accomplishments at Nachusa are making strong contributions to both scientific understanding and on-the-ground conservation and restoration efforts. Thank you all for being part of this. None of this could happen without the collaboration of scientists, volunteers, donors, The Nature Conservancy, and Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Many of the 2021 researchers were supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants.

The Nachusa summer science externship is supported by The Nature Conservancy. By Elizabeth Bach Ecosystem Restoration Scientist With 2020 drawing to a close, Nachusa science has several accomplishments to recognize:

Science PublicationsScientific publications are the product of years of hard work, collecting and analyzing data as well as writing the paper. I’d like to use this blog post to highlight some of this recently published research. It has been an exciting year for Dr. Holly Jones, Dr. Nick Barber, and their lab groups. Holly and Nick began research at Nachusa Grasslands in 2013 as new faculty at Northern Illinois University (Nick is now at San Diego State University). Their work investigates restoration outcomes related to planting age, prescribed fire, and grazing. In 2020, the team has published five papers:

The Wildlife Epidemiology Lab, led by Dr. Matt Allender, at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has included Nachusa Grasslands as one of their sites in on-going health evaluations of wild turtle populations. Research scientist Dr. Laura Adamovicz has published three papers from her PhD dissertation:

Devin Edmonds, who is a graduate student with Dr. Michael Dreslik at UI-UC and the Illinois Natural History Survey, examined Reproductive output of ornate box turtles (Terrapene ornate) in Illinois, USA. This is the first assessment of ornate box turtle reproduction in Illinois. Meghan Garfinkel earned her PhD from University of Illinois-Chicago this spring. Her research quantified crop pest suppression by songbirds. She found Birds suppress pests in corn but release them in soybean crops within a mixed prairie/agriculture system. Additional data is needed to see if these results can be applied more broadly on the landscape and across years. These initial results indicate birds could provide sizable services to agricultural land around prairie habitat. Physlis Pischl, a PhD student at Northern Illinois University, performed an elegant analysis of Plastome phylogenomics and phylogenetic diversity of endangered and threatened grassland species (Poaceae) in a North American tallgrass prairie. The work showed endangered and threatened grass species were more closely related than expected and likely evolved together in specific grassland habitats. Destruction of those habitats have resulted in many closely related species all being endangered and threatened. Read more about this study. John Vanek shared his work with Dr. Rich King surveying snake communities at Nachusa in this recent blog. John also published Observations of American Badgers, Taxidea taxus (Schreber, 1777) (Mammalia, Carnivora), in a restored tallgrass prairie in Illinois, USA, with a new county record of successful reproduction. While it is no surprise to find badgers at Nachusa, this is a new confirmed report of breeding badgers. Hana Thixton found Further evidence of Ceratobasidium serving as the ubiquitous fungal associate of Platanthera leucophaea (Orchidaceae) in the North American tallgrass prairie (open access) in her MSc research with Dr. Betsy Esselman at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Ceratobasidium fungi were by far the dominant fungal partner for EPFO, and genetic diversity of those strains was limited, indicating the fungal partners were consistent across sites. Drew Scott found Plant diversity decreases potential nitrous oxide emissions from restored agricultural soil in this research as part of his PhD dissertation at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. In this study, he found nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change, from soils at Nachusa with high plant diversity were about seven times lower than from areas with low plant diversity. View the complete list of Nachusa publications. By Chandler Dolan Bumble Bee Technician Introduction The scene: It’s a classically humid, July afternoon. A gaze across the prairie shows patches of yellows and pinks, suggesting the presence of yellow coneflower and wild bergamot. As the heat intensifies, the birds and bison seem to slow. You stand quietly, intently listening to the sounds the grassland offers. Suddenly, a loud buzz tears through the patterns of bird melodies and katydid song. A familiar yellow and black face emerges from under a canopy of partridge pea: a bumble bee. Bumble bees are familiar insects. The shaggy combination of yellow and black (and sometimes orange) hairs with a plump, round build makes these insects nearly unmistakable. Their role of pollinating beautiful wildflowers and food plants alike is an important ecosystem service they provide us, free of charge. Their friendly buzz and frantic foraging suggest a healthy ecological system. Unfortunately, bumble bees face an uncertain future. Through habitat loss, pesticide use, and disease, many bumble species have experienced significant decline and are becoming increasingly rare. Thankfully, Nachusa gives refuge to three threatened species of bumble bees, including the critically endangered rusty-patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis). In 2017, Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar discovered the presence of the rare bumble bee at Nachusa in the form of a foraging worker. This was a great discovery, as the current distribution of the species is fairly unknown. To know this species was living at Nachusa was special and has given rise to new research opportunities and questions to be answered. With the new motivation of a federally endangered species in the Grasslands, new projects have begun! The 2020 season is the first season we have boots on the ground (in the form of me!) to monitor bumble bee abundance and diversity across all species of bumble bee at Nachusa. We start with simple questions: What species of bumble bees are here? How many of them are there? What flowers are they using? By answering these questions, we can start to form new questions and learn about the Grasslands. This season is all about exploration, experimentation, and just getting a sense of the bumble bees at Nachusa. Endangered Bumble Bees of Nachusa Grasslands As mentioned, the rusty-patched bumble bee is a federally recognized endangered species in the United States. In fact, it is the first bumble bee species to be listed on the United States Endangered Species Act. This characteristic bumble bee sports a unique “rusty patch” on its abdomen, which is one of its best identification traits, hence the name. The decline of this species is somewhat mysterious and very sudden. Prior to 1996, this species was abundant throughout much of the Midwest and Northeastern U.S. After 1996, the species tumbled into rapid decline and is now extremely rare in the Northeast. Most records of this species today are sporadically reported in the Midwest, but at very low rates. In the seven weeks I have been surveying, I have detected two rusty-patched bumble bee workers at Nachusa. To know this species is still present and not extinct is a great discovery alone. But understanding the way it uses the mosaic and where it chooses to nest is still up for question, and is difficult to answer with such sparse sightings. Our first sighting occurred very early in the field season. In fact, it was the fourth day of surveying! Seeing a single rusty-patched worker busily foraging on beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis) was a great way to start the season. Our second was about a month later on July 17th. Upon my arrival to a hill to do some quick exploration, the very first bee I spotted was the rare but distinct bumble bee methodically feeding on wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa). I held back tears of joy as I quickly netted the bee for proper identification. Nachusa also houses two other declining bumble bee species: the golden yellow bumble bee (Bombus fervidus) and the American bumble bee (Bombus pensylvanicus). Bombus fervidus has quickly become one of my favorite species, as its striking yellow abdomen and bold, black thorax band are impossible to miss. While these species are not recognized as endangered by the federal government, they have documented declines that warrant them a “vulnerable to extinction” assessment by the IUCN Redlist. I’m happy to report that these species are detected regularly and seem to like certain parts of the Grasslands. One day we hope to answer these questions: What parts of Nachusa are these vulnerable species found, and why? What makes one patch of habitat more suitable than another? Conclusion Bumble bees are interesting. Their familiarity provides a calming energy, as their small wings effortlessly lift their seemingly oversized bodies and loads of pollen to provide for the nest and its offspring. But despite how recognizable they may be, there is still much to learn about them. Simple things such as their habitat and favorite flowers are yet to be fully understood. A closer look into the world of bumble bees reveals a world of individual decision-making by our hairy friends that we are working hard to better understand. One of the first steps to conserving a species is to better our understanding of them. With the first long-term bumble bee surveying season at Nachusa underway, we hope to better understand our bumble bees and to one day provide them the best habitat we can. To lose a species is to lose a piece of a puzzle. Once gone, the picture will never be the same, with a hole no other piece can fill. *** UPDATE: On July 29th and 30th, two more rusty-patched bumble bees were observed at Nachusa! That makes a total of 4 observations this season! *** Dr. Bethanne Bruninga-Socolar's ongoing research on Nachusa's bumble bees is supported with a Scientific Research Grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. If you would like to play a part in helping the bees at Nachusa Grasslands, consider joining our Thursday or Saturday Workdays or giving a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. Donations to Friends can be designated to Scientific Research Grants. Chandler Dolan graduated from the University of Northern Iowa in December of 2019. Throughout Chandler's career as a young biologist, they have been continually drawn to endangered species ranging from the rusty-patched bumble bee to neotropical parrots and migratory songbirds. As Chandler dives deeper into the world of bumble bees, they hope to pursue bumble bee conservation as a long-term goal for graduate school.

By Jess Fliginger In 2013, Dr. Holly Jones started conducting a long-term research project at Nachusa Grasslands on quantifying the effects of disturbance-related management strategies on small mammal populations at restored and remnant prairie sites. The reintroduction of bison in 2014 allowed for a powerful before and after bison impact study that documented the effects of bison grazing on the small mammal communities. Data collected on species responses to bison, prescribed fire frequency, restoration age, and vegetation composition will inform decisions regarding abundance and biodiversity for small mammals. Small mammals play important roles in the food web by influencing vegetation structure through herbivory and seed predation, as well as serving as prey for predator species. So far, plant communities with bison grazing are becoming more diverse and more abundant with small mammals. In the beginning, Dr. Jones ran the small mammal project by herself for a year until she was able to pass it on to her Master’s student Angela Burke in 2014. It was quite a challenge to run the project on her own, and volunteers have become an essential component to keep it going. Over the years, we have had more than 100 volunteers participate to help check traps in the morning and reset traps in the afternoon. On the first day of small mammal trapping, or as we like to call it “smammaling”, we prep 150 metal Sherman traps by baiting them with peanut butter and oats. Our small army of volunteers, 3 or 4 people, create an assembly line, with one person spreading just a dab of peanut butter on the backplate and the other sprinkling a small pinch of oats inside. Once all traps have been prepped, we start stacking rows of them, Tetris style, in the back of Scarlet, our NIU mule.  Out of the four seasons we sample for small mammals, August and October have the tallest vegetation, making it difficult to locate our poles. We flag the highest plant we can find nearby; for me it’s usually prairie dock or good ol’ big bluestem, and we try to navigate our way through the meandering paths of the tallgrass prairie jungle." We take off to set 25 traps at six of our 5x5 grid sites, hoping our plans don’t get foiled by any bison delays or strange weather. Each site has flagged poles to indicate where the trap must be set; however, finding them can sometimes be a challenge. Bison love using our poles as backscratchers, and they are often found sprawled across the prairie. At each pole we place an open trap where it will sit until an unsuspecting critter passes by and catches a whiff of irresistible Jif.  The mice spend the night at their “mouse hotel” feasting on peanut butter and oats until we are back to process them in the morning. I always get a rush of excitement as I walk up to a trap and notice the door is closed. When I peek inside the trap, I am usually able to see a little face staring back at me. Occasionally, I’ll get a trigger-no-capture and my excitement will fade to dissatisfaction. Likewise, thieves are a constant problem. Some especially small, speedy daredevils are able to run in to the trap, take some quick bites of peanut butter, and run out without triggering it. We keep tabs on which traps have been thieved and adjust/replace them accordingly. To process the small mammals, we record the weight and take measurements on the right hind foot, tail, and body using a caliper. In addition, we determine their sex, age, reproductive status, species, and PIT tag number. Some of the species we have captured at our sites and record data on include thirteen-lined ground squirrel, deer mouse, white-footed mouse, western harvest mouse, meadow jumping mouse, prairie vole, meadow vole, and masked and short-tailed shrews. The most common species we capture is the deer mouse, Peromyscus maniculatus. Depending on whether it’s a new capture or recap, we will carefully insert a PIT tag underneath its skin – similar to microchipping your pet – as a way to keep track of its movements, survival, and reproduction throughout the study. It’s always a treat when we have an overwinter or recapture from the previous year; they were the lucky ones to survive the long cold winter! Finally, we provide complimentary haircuts to all new buddies and collect the hair to run in the stable isotope lab. The information gathered from each sample result can tell us about their diet and role in the food web. Since 2015, I have been volunteering with Dr. Jones’ small mammal project. This year I was given the opportunity to help run the project and process the small mammals until her incoming PhD student, Erin Rowland, arrived. I took up the challenge, and with practice I became a pro. I would say my favorite part of the job is meeting the volunteers and training them how to be great smammalers. I enjoy acting as a Nachusa tour guide to all newcomers, young and old. Although anyone is welcome to volunteer, the majority of our helpers are undergraduate students who enjoy a break away from the classroom. Volunteering for the small mammal project gets you to spend time outside, which is beneficial to your health and well-being. It inspires the public to engage in the scientific process, appreciate native plants and animals, and meet others who care about our environment. Furthermore, it helps develop team building skills that are important for any job setting. Volunteers are the heart and soul of the small mammal project, and without them I’m not sure it would be able to persist. There is a lot to accomplish within the 12 consecutive days we are at Nachusa smammaling, and any help is greatly appreciated! If you are interested in volunteering, please contact Erin Rowland. To me, the small mammal project is all about making new and old friends — volunteers and mice alike. Small mammal research has been supported by the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands science grants from 2015 to 2018.

Consider a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands to support the ongoing science! “Today you can stand anywhere on the 23-acre plot and see all the way across it in any direction. Previously, the woody invasives blocked the view. Now the prairie species will have space and sunlight to bloom and thrive.” --Mike Carr, Orland Prairie Steward By Dee Hudson Nachusa Grasslands Steward Asian honeysuckle and autumn olive brush were quite thick throughout a 23-acre plot of Nachusa’s Orland Prairie. Ten years of mowing and burning these invasives had little effect, as the shrubs kept resprouting. As long as these invasive shrubs remained, the native plants were suppressed. In order to help restore Orland Prairie, Friends of Nachusa Grasslands applied for a stewardship grant from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation. The objective of the Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program of the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation is to encourage increased community participation in the care of natural areas and wildlife habitat managed by non-profit organizations in Illinois. The grant provided support to Friends of Nachusa Grasslands in a several ways: A Cash Donation Match Challenge

Volunteer Stewardship Challenge

Social Media Challenge

Equipment Purchase

Come see Orland Prairie! Join steward, Mike Carr, as he leads a tour of the project site at Nachusa Grasslands’ Autumn on the Prairie on Saturday, September 21, from 2:45 to 4 pm. See the areas newly-cleared of dense brush and enjoy the young plants moving into the bare ground. Friends of Nachusa Grasslands would like to thank Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation for motivating and supporting our organization in this invaluable effort.

@illnoiscleanenergycommunityfoundation #CSgrantsIL #NAicecfdn By Jeff Cologna and Joy McKinney

Each steward at Nachusa Grasslands has a fascinating personal tale, often involving stories of sacrifice, setbacks, and success. Together, with the resources of The Nature Conservancy, volunteers, donors, and Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation, stewards work hard to ensure Illinois prairie is not merely a fading memory, but a lasting reality for all future generations. Mike Carr, one of these amazing stewards, shared a few stories from the past with us. The following paragraphs highlight those early days. Mike’s story began as a boy whose father loved the great outdoors but "bemoaned endlessly about all the invasive plants.” His father, Francis Carr, taught him about invasive plants and how to identify trees by their bark, enabling him to identify them all year ‘round. Little did he know back then that these skills and a disdain for invasives would serve him so well at Nachusa. In the Spring of 2010, soon after “getting away” from the city of Chicago, Mike found himself “banging on the door” of Bill Kleiman, Nachusa’s Director. Early in their discussions, Bill explained how critical fire is to restoring and maintaining healthy prairie landscapes. Experience managing fire became a top priority. Mike quickly completed a 40-hour online fire certification class leading to an absolute “love of fire” as well as the acquisition of key skills for participating in controlled burns. Mike was then challenged by Bill Kleiman and Cody Considine, restoration ecologist at Nachusa, to take on a unit of his very own which would later be named Big Jump. We asked Mike why the 350-acre unit was given this interesting moniker. Apparently, it was the result of a naming contest among stewards. His unit is basically “a long way from the HQ.” Due to the number of high-quality remnants within its boundaries, Mike’s restoration activities have opened up the landscape, enabling unseen natives such as porcupine grass, arrow leaf violets, and blue-eyed grass to show themselves, surprising and delighting Mike. Every year he discovers new “surprises” that weren’t there before. “The whole hillside of one remnant is filled with violets in the spring and another remnant with Carolina rose, bird’s foot violet, comandra, and pussy toes. Mike focused his efforts on a 23-acre plot within the unit which is now known as “Orland Prairie." In the beginning of restoration, Mike shared that Orland Prairie needed some kind of push to get rid of all the invasive woodies (shrubs and bushes) so the prairie could find its way. In the last 10 years, Nachusa’s Fecon mower was used to knock down the invasive woodies. Seed, collected by combine, was then spread on the area, beginning the restoration process. Unfortunately, woodies continue to dominate. Restoration efforts continue at Orland Prairie with the help of a generous grant from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation. The grant is being used in part to purchase herbicide for continued eradication of the highly invasive autumn olive plant and other woodies. The application of the basal bark herbicide is highly effective. “If you stand next to an autumn olive and you tell it that you’ll come back with basal bark . . . it’ll just die!” Mike quipped. Basal bark applications have been used to successfully eradicate infestations of autumn olives, which at one time stood up to 15 ft high and covered the entire 23 acres. Mike shared that the herbicide is most effective after a fire.

Mike Carr is just one of the many dedicated men and women who have committed to making Nachusa Grasslands more than just a memory. We would like to thank Mike’s dad for inspiring him to be patient and dedicated to long term goals and above all, valuing and respecting nature. Come meet Mike on the March 2nd workday to see the Orland Prairie and experience the whimsical beauty of Nachusa Grasslands! By Dee Hudson What does a degraded landscape look like? Take a good look at the image below. The two volunteer stewards can barely walk through this dense thicket of invasive bushes. The sheer number of invasives that reside here have crowded out most other species, and as a result, have limited the possible diversity. In addition, when leafed out during the summer time, the bushes block the sunlight from reaching the ground and therefore discourage native species from growth. As Orland Prairie’s land steward, Mike Carr led the December 8 Saturday workday into this gnarly section in the attempt to eradicate the invasive brush. At the end of the day, each volunteer stewardship hour was carefully logged, because Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation has approved this particular habitat as a grant project. When 400 volunteer hours of habitat care have been recorded, Illinois Clean Energy will present $4,000 to Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. What species are targeted for removal?

How is the brush eradicated? On this workday the volunteers treated the brush with basal bark applications. The treatment was applied to the base of the bush with either a backpack sprayer or a hand sprayer. What does a restored landscape look like? This landscape is also a part of the 23-acre grant project. The area once looked very degraded, but with basal bark treatments and prescribed fire, the brush understory was removed. Then prairie seeds were planted and the photo above shows the successful restored results. This area has been given new life and is on its way to recovery. Who restores these habitats? Anyone who wants to make a difference can help with restoration!

Next ICE Grant Workday Join fellow volunteers on December 22, 2018 for the next ICE Grant Saturday workday. Meet at Nachusa’s Headquarters Barn before 9 am and be ready to restore habitat. If you have any questions about the workdays, check the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website. Let’s make a difference together! Connect with Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation: @illnoiscleanenergycommunityfoundation

#CSgrantsIL #NAicecfdn |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed