|

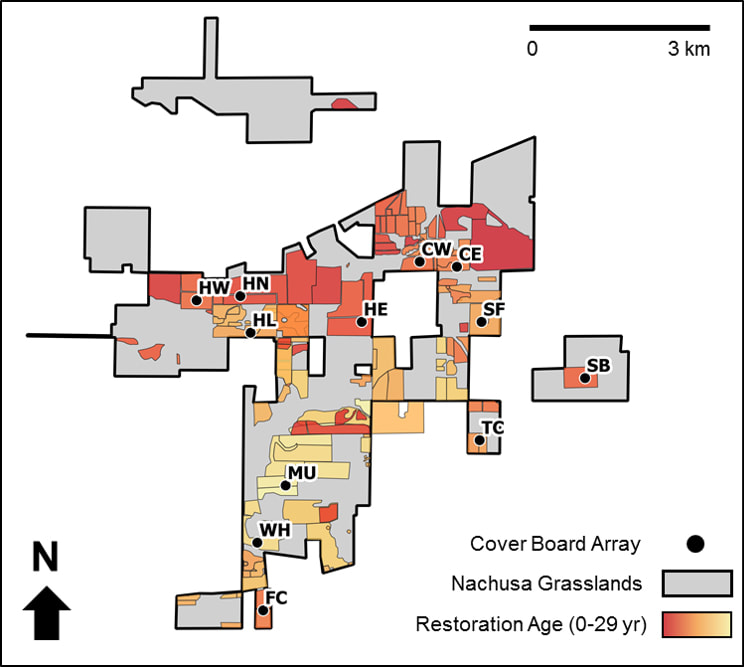

By John Vanek, PhD Associate Wildlife Biologist® As scientists, we know a lot about snakes. We know that snakes evolved from lizards. We know that snakes don’t have eyelids or external ears. We know they can eat things bigger than their own head. Some species, like the black-tailed rattlesnake, are good mothers, stick around after birth, and protect their offspring. Recently, it was discovered the snakes can even have friends! Suffice it to say, snakes are awesome. So awesome, in fact, that some of us prefer them to grasshopper sparrows and fringed gentians (don’t hit me!). Yes, we herpetologists (scientists that study reptiles and amphibians) are a weird bunch, with our metal probes and pillowcases . . . anyway, I digress. While we know a lot about snakes and how cool they are, we still have a lot to learn, particularly when it comes to ecological restoration. Unlike birds and insects, snakes don’t have wings. Snakes are also terrible at crossing roads (probably because they don’t have legs). So, the big question is if you build it, will they come? That is, if you go through the hard work of restoring an old ag field back to tallgrass prairie, will snakes recolonize the site? Dr. Richard King and I tried to tackle this question in a recent publication creatively titled “Responses of Grassland Snakes to Tallgrass Prairie Restoration.” In short, yes, but it’s complicated!  The eastern fox snake (Pantherophis vulpinus) is one of many species that make Nachusa Grasslands their home. Friend to the farmer, this species feeds mostly on rodents. Unfortunately, due to a habit of vibrating their tail (see video at the end), they are often confused for rattlesnakes and killed. Before we dive into what we found, how do herpetologists actually study snakes? It’s not like you can lean against a shady bur oak and listen for the sounds of singing snakes (yes, this is a playful dig at my ornithologist friends). One option is to simply walk around and look for snakes. This is, however, not very effective. Think of how many snakes you’ve stumbled across at Nachusa. Maybe a handful at most, right? Certainly not enough to do some fancy statistics. Nor will snakes stumble into a tiny metal box baited with peanut butter (sorry mammologist friends, I had to make it fair to the ornithologists!). So, what is the intrepid herpetologist to do? We take advantage of a snake’s natural tendency to hide under things, so we employ something called “artificial cover object surveys.” What this means is that we put out things that snakes will hide under (in our case plywood boards and rubber mats), and then go back later and check each one. What does a check entail, you may ask? Great question, and the answer is simple: bend down, lift the board, and then try to grab every snake you see! Simple, but not easy; those little buggers are fast! An unexpectedly large common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) found under a board. Even seasoned herpetologists get impressed by big snakes! Now the nuts and bolts of our study. To address the question of snakes and habitat restoration, we deployed approximately 240 snake boards across 12 restoration units (2–25 years since restoration) at Nachusa. We (ok, mostly Rich) checked each board roughly once a week from May to October from 2013–2016. This resulted in sacrificing our lower backs for science a total of 15,720 times over the four years. (The astute reader may notice the math doesn’t work out perfectly, and that’s because life often gets in the way of checking snake boards!) Was it worth it? You bet! Overall, we caught 1,028 individual snakes of four focal species: 90 plains garter snakes, 112 eastern fox snakes, 347 Dekay’s brown snakes, and 479 common garter snakes. Each snake was given a unique marking so we could identify it if captured again, and we also measured and weighed each snake. We also found a few other species in small numbers. Right off the bat, we see that all four species readily colonized tallgrass prairie restorations at Nachusa, which is great news! We also found that there was no relationship between restoration age and the abundance or occupancy of plains garter snakes, eastern fox snakes, or common garter snakes. That is, newly-restored sites were just as likely to have these species as older restorations. However, older sites were much more likely to have Dekay’s brown snakes than younger sites. This is a really cool finding, as Dekay’s brown snakes are the smallest of the four species (adults rarely exceed 18 inches), and they also have the smallest home ranges. This suggests that smaller species with limited dispersal capabilities might be slower to colonize restorations. Intuitive for sure, but it’s always great to have data! Finally, there was a glaring omission from our snake board data: we found zero smooth green snakes! This was really odd, as the species was once common across northern Illinois, and we found them to be relatively common at nearby Green River Wildlife Management Area. However, snakes can be really hard to find, so the question became, “Are smooth green snakes truly absent from Nachusa, or did we simply fail to find them?” To address this, we took our data from Green River and used a statistical technique called logistic regression to calculate something called a "detection probability". The results? Given our approximately 15,000 cover board checks, we estimated there was a 99.9% chance we would have detected them if they were indeed present at Nachusa. Could we have missed them? Certainly, but it is highly unlikely. So, why are there no smooth green snakes at Nachusa? The most likely explanation is that they simply did not survive in the small remnants at Nachusa prior to restoration. Like Dekay’s brown snakes, smooth green snakes are quite small and are probably not so great at colonizing new areas. In addition, smooth green snakes specialize on eating insects and spiders, and they may be particularly susceptible to insecticide use relative to other species with broader diets. So, if they didn’t survive at Nachusa, crossing miles of roads and ag fields might pose too big of a challenge. Therefore, while a “wait and see” approach might work for other species (such as Dekay's brown snake), captive breeding and translocation may be necessary to establish populations of smooth green snakes at Nachusa. This approach has shown great promise in the Chicago suburbs, and I hope one day to see the tail end of a smooth green snake slipping away into a tussock of little bluestem at Nachusa Grasslands. In conclusion, we found that Nachusa boasts plentiful populations of at least four species of grassland snake, and these snakes are not limited to the remnants, but occur broadly throughout restoration units. Other species also occur, including the eastern hog-nosed snake, eastern milk snake, North American racer, and common water snake. However, the smooth green snake, a species that is common in nearby Green River Management Area, appears to be truly absent at Nachusa. I propose they be considered a candidate for assisted translocation or reintroduction, pending further study, of course. Thanks for reading! Have you seen any snakes at Nachusa? If so, what kind? Let me know in the comments, and feel free to send me an email for snake identification help from Nachusa or anywhere else! Many harmless snakes, such as this eastern fox snake (Pantherophis vulpinus), will defensively vibrate their tails.

8 Comments

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed