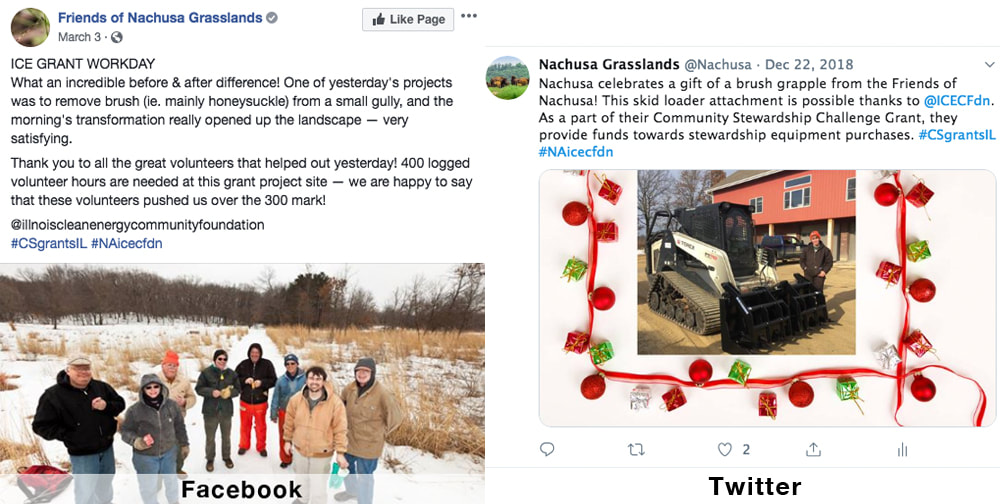

“Today you can stand anywhere on the 23-acre plot and see all the way across it in any direction. Previously, the woody invasives blocked the view. Now the prairie species will have space and sunlight to bloom and thrive.” --Mike Carr, Orland Prairie Steward By Dee Hudson Nachusa Grasslands Steward Asian honeysuckle and autumn olive brush were quite thick throughout a 23-acre plot of Nachusa’s Orland Prairie. Ten years of mowing and burning these invasives had little effect, as the shrubs kept resprouting. As long as these invasive shrubs remained, the native plants were suppressed. In order to help restore Orland Prairie, Friends of Nachusa Grasslands applied for a stewardship grant from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation. The objective of the Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program of the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation is to encourage increased community participation in the care of natural areas and wildlife habitat managed by non-profit organizations in Illinois. The grant provided support to Friends of Nachusa Grasslands in a several ways: A Cash Donation Match Challenge

Volunteer Stewardship Challenge

Social Media Challenge

Equipment Purchase

Come see Orland Prairie! Join steward, Mike Carr, as he leads a tour of the project site at Nachusa Grasslands’ Autumn on the Prairie on Saturday, September 21, from 2:45 to 4 pm. See the areas newly-cleared of dense brush and enjoy the young plants moving into the bare ground. Friends of Nachusa Grasslands would like to thank Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation for motivating and supporting our organization in this invaluable effort.

@illnoiscleanenergycommunityfoundation #CSgrantsIL #NAicecfdn

2 Comments

By Leah Kleiman Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) is a perennial shrub native to temperate Asia and is invasive in the Midwestern United States. It now infests many savannas and woodlands and is difficult to eradicate. Bill and Susan Kleiman and I are co-authors of a study recently published in the journal Ecological Restoration, titled “The Successful Control of Lonicera maackii (Amur honeysuckle) with Basal Bark Herbicide” (http://er.uwpress.org/content/36/4/267.full.pdf+html). Our study looked at the efficacy of basal bark application, where a mineral oil solution of herbicide is sprayed in a 6-inch band on the bark without cutting the plant. Our study found 100% mortality with basal bark treatment. A variety of other treatment methods are used to battle honeysuckle. Manual pulling works well on small individuals in soft ground, but becomes impossible with larger sizes. Cutting and treating the stumps with herbicide is effective, but very time-consuming. We recommend the cut-and-treat method for sensitive high-quality areas. A foliar spray of herbicide is effective and efficient, but will have much more off-target damage and can only be used in the growing season. Fire is a useful tool in keeping brush at bay, but it will only top-kill shrubs. The basal bark method is efficient, effective in all seasons, and has minimal off-target damage. Some things to keep in mind: 1) Re-treating is important for success. One treatment is not enough. Some shrubs will inevitably be missed, and yearly recruitment will occur until the seedbank is exhausted. 2) Honeysuckle treated in the dormant season may still leaf out and die later in the growing season. So if you notice this, it does not mean that your treatment has failed, but rather that you need to check back at a later date (typically late summer/fall). Our study concludes that basal bark treatment paired with regular fire is the optimal way to eradicate honeysuckle invasions. For more information on treating honeysuckle with basal bark, see the February 3, 2019 blog post “A Study on Controlling Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii)” by Kaleb Baker.

By Jeff Cologna and Joy McKinney

Each steward at Nachusa Grasslands has a fascinating personal tale, often involving stories of sacrifice, setbacks, and success. Together, with the resources of The Nature Conservancy, volunteers, donors, and Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation, stewards work hard to ensure Illinois prairie is not merely a fading memory, but a lasting reality for all future generations. Mike Carr, one of these amazing stewards, shared a few stories from the past with us. The following paragraphs highlight those early days. Mike’s story began as a boy whose father loved the great outdoors but "bemoaned endlessly about all the invasive plants.” His father, Francis Carr, taught him about invasive plants and how to identify trees by their bark, enabling him to identify them all year ‘round. Little did he know back then that these skills and a disdain for invasives would serve him so well at Nachusa. In the Spring of 2010, soon after “getting away” from the city of Chicago, Mike found himself “banging on the door” of Bill Kleiman, Nachusa’s Director. Early in their discussions, Bill explained how critical fire is to restoring and maintaining healthy prairie landscapes. Experience managing fire became a top priority. Mike quickly completed a 40-hour online fire certification class leading to an absolute “love of fire” as well as the acquisition of key skills for participating in controlled burns. Mike was then challenged by Bill Kleiman and Cody Considine, restoration ecologist at Nachusa, to take on a unit of his very own which would later be named Big Jump. We asked Mike why the 350-acre unit was given this interesting moniker. Apparently, it was the result of a naming contest among stewards. His unit is basically “a long way from the HQ.” Due to the number of high-quality remnants within its boundaries, Mike’s restoration activities have opened up the landscape, enabling unseen natives such as porcupine grass, arrow leaf violets, and blue-eyed grass to show themselves, surprising and delighting Mike. Every year he discovers new “surprises” that weren’t there before. “The whole hillside of one remnant is filled with violets in the spring and another remnant with Carolina rose, bird’s foot violet, comandra, and pussy toes. Mike focused his efforts on a 23-acre plot within the unit which is now known as “Orland Prairie." In the beginning of restoration, Mike shared that Orland Prairie needed some kind of push to get rid of all the invasive woodies (shrubs and bushes) so the prairie could find its way. In the last 10 years, Nachusa’s Fecon mower was used to knock down the invasive woodies. Seed, collected by combine, was then spread on the area, beginning the restoration process. Unfortunately, woodies continue to dominate. Restoration efforts continue at Orland Prairie with the help of a generous grant from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation. The grant is being used in part to purchase herbicide for continued eradication of the highly invasive autumn olive plant and other woodies. The application of the basal bark herbicide is highly effective. “If you stand next to an autumn olive and you tell it that you’ll come back with basal bark . . . it’ll just die!” Mike quipped. Basal bark applications have been used to successfully eradicate infestations of autumn olives, which at one time stood up to 15 ft high and covered the entire 23 acres. Mike shared that the herbicide is most effective after a fire.

Mike Carr is just one of the many dedicated men and women who have committed to making Nachusa Grasslands more than just a memory. We would like to thank Mike’s dad for inspiring him to be patient and dedicated to long term goals and above all, valuing and respecting nature. Come meet Mike on the March 2nd workday to see the Orland Prairie and experience the whimsical beauty of Nachusa Grasslands!

By Kaleb Baker

Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) is an invasive shrub that flourishes along forest edges and in open woodlands such as those at Nachusa Grasslands. Amur honeysuckle shades out native flora with its early leaf-out and prolonged leaf retention, and when left uncontrolled, can produce a near monoculture, threatening biodiversity.

Land stewards everywhere have implemented a variety of different eradication methods, including hand pulling, cut-and-treat with herbicide, foliar-applied herbicide from backpacks or helicopters, basal bark herbicide treatments, and prescribed fire. Continuous treatments and monitoring are needed to eradicate Amur honeysuckle, making the cost, effort, and time requirements of controls important.

Knowing the efforts we go through to manage honeysuckle, as well as the amount of conjecture surrounding the best practices, I worked with my advisor Dr. Nick Barber to study how effective basal bark treatments and prescribed fire are at controlling honeysuckle., I decided to study how effective basal bark treatments and prescribed fire are at controlling honeysuckle. Basal bark and fire are regularly-used control methods at Nachusa. Basal bark treatments involved spraying a 20% solution of triclopyr herbicide around each plant’s base from a backpack, which was both quick and easy. In this study I included 800 individually-marked Amur honeysuckle at 5 different sites within Nachusa Grasslands and Franklin Creek State Natural Area. Basal bark treatments were applied in fall 2017, winter 2018, early spring 2018, and late spring 2018 to see if the season of application affected the mortality of honeysuckle or the extent of damage to non-target flora. Prescribed fire was administered to half of each of the 5 sites in spring 2018. I then checked mortality in the early fall of 2018 to allow the honeysuckle time to either drop its leaves and regrow them (falsely dead) or to retain its leaves for an extended period of time before dying (falsely alive).

I found that basal bark applications were equally effective at killing Amur honeysuckle, regardless of treatment timing. The combined mortality rate of herbicide treatments was 98.4% across all herbicide treatment seasons, compared to a 2.5% mortality with no basal bark treatment. Prescribed fire did not impact mortality positively or negatively.

I also placed a 1m2 quadrat around 200 Amur honeysuckle to measure off-target damage to the plant community in spring 2018, finding a decrease of living cover equating to about a 10-inch radius. The off-target “ring of death” did not differ based on fire treatment or basal bark season.

I was lucky to receive a grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands where I will be able to return in May 2019 to resample the off-target vegetation quadrats to evaluate how quickly the flora recover from the various treatments.

From my current results, I highly recommend using basal bark treatments to control Amur honeysuckle for all but the highest quality of areas. The speed and ease of use allow managers to cover large swaths of invaded areas across fall, winter, and spring seasons. The standing dead material from the honeysuckle can be reduced with a masticator or brush mower in the non-growing season or with regular prescribed fire, which should be implemented anyway.

Kaleb Baker is a Master's Candidate at Northern Illinois University, focused on natural areas management practices, and current Stewardship Committee Chair for Franklin Creek Conservation Association.

By Dee Hudson What does a degraded landscape look like? Take a good look at the image below. The two volunteer stewards can barely walk through this dense thicket of invasive bushes. The sheer number of invasives that reside here have crowded out most other species, and as a result, have limited the possible diversity. In addition, when leafed out during the summer time, the bushes block the sunlight from reaching the ground and therefore discourage native species from growth. As Orland Prairie’s land steward, Mike Carr led the December 8 Saturday workday into this gnarly section in the attempt to eradicate the invasive brush. At the end of the day, each volunteer stewardship hour was carefully logged, because Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation has approved this particular habitat as a grant project. When 400 volunteer hours of habitat care have been recorded, Illinois Clean Energy will present $4,000 to Friends of Nachusa Grasslands. What species are targeted for removal?

How is the brush eradicated? On this workday the volunteers treated the brush with basal bark applications. The treatment was applied to the base of the bush with either a backpack sprayer or a hand sprayer. What does a restored landscape look like? This landscape is also a part of the 23-acre grant project. The area once looked very degraded, but with basal bark treatments and prescribed fire, the brush understory was removed. Then prairie seeds were planted and the photo above shows the successful restored results. This area has been given new life and is on its way to recovery. Who restores these habitats? Anyone who wants to make a difference can help with restoration!

Next ICE Grant Workday Join fellow volunteers on December 22, 2018 for the next ICE Grant Saturday workday. Meet at Nachusa’s Headquarters Barn before 9 am and be ready to restore habitat. If you have any questions about the workdays, check the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands website. Let’s make a difference together! Connect with Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation: @illnoiscleanenergycommunityfoundation

#CSgrantsIL #NAicecfdn By Leah Kleiman Summer is a busy time of year on the prairie with invasive weeds sprouting up and native plants going to seed. That's why every year Nachusa hires half a dozen seasonal staff to keep up with the workload from May through November. Typically the hired staff are in their twenties and going into careers in ecological restoration/conservation. During May, June, and July we will spend the majority of our time spraying and spading invasive weeds in the hot sun to keep them from taking over the prairie plantings. Backpack sprayers are used to apply herbicide to weeds such as sweet clover and bird's foot trefoil until they start going to seed. Then we will pull them by hand. By mid-August weed season is over and it's time to focus on seed collection. As each native plant species ripens, the crew will go out and collect them by hand in buckets and barrels. We may collect anywhere between a few ounces to several hundred pounds, depending on the species size and density. After the seed is collected it will be dried on racks in our seed barn and then milled to separate the seed from the chaff. In the late fall the crew will spread the seed we collected in brand new plantings that have not seen prairie in recent years. This year we will plant several areas with a range of habitats. For the most part the seed mixes will be spread using seeders pulled behind trucks and utility terrain vehicles. The crew of 2018 has already covered a lot of ground in weed sweeps and collected some precious prairie plants. Stay tuned for another crew report in the fall! Meet this year's hardworkersNathaniel Weickert is the crew leader, and this is his second summer working at Nachusa. He is from Rockford and received his Bachelors in Biological Sciences from NIU in 2015. He hopes to acquire a Masters degree and continue working in the field of restoration and conservation. In his free time Nathaniel enjoys reading, hanging out with his friends and family, and producing art. Avery Parmiter is from Connecticut and earned her B.S. in Environmental and Natural Resource Management from Clemson University in 2015. Avery would like to continue to be based in the field of conservation and looks forward to furthering her knowledge about restoration ecology in her second year at Nachusa. In her free time she enjoys traveling and exploring natural areas. Kim Elsenbroek is from Kingston, Illinois and earned her B.S. in Plant Biology from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale in 2012 and her M.S. in Evolution, Ecology and Behavioral Biology in 2015 from Indiana University at Bloomington in 2015. She was also on the crew in the fall of 2015. Kim aspires to continue working in the field of restoration and conservation as a practitioner, researcher, and/or teacher. In her free time Kim is a dancer and dance teacher/choreographer at Dance Dimensions in DeKalb. Tyler Berndt is from Minooka Illinois. He recently graduated from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale with a BS in Zoology Wildlife Biology and is currently seeking graduate level opportunities. Tyler had previously worked at Nachusa as an undergraduate ornate box turtle technician. He values learning more about the political and interpersonal deliberations needed to connect fragmented habitats and human dominated ecosystems. Tyler would like to be a consultant or coordinator for organizations like The Nature Conservancy and the USDA Forest Service. In his free time he enjoys exploring state and national parks, historical sites, and cities. Karey O'Brien is from Minooka Illinois and graduated with a B.S. in Environmental Science from Lewis University. She recently worked at the Forest Preserve District of Will County as a Natural Resource Management Seasonal Laborer. Karey hopes to improve her plant identification skills and continue learning more about natural areas management while here at Nachusa. In her free time Karey enjoys hiking, biking, and watching movies. Leah Kleiman is a volunteer. This is her second summer working with the crew. She grew up on Nachusa and is working on her A.S. in biology at Sauk Valley Community College. Next year Leah will be transferring to Southern Illinois University at Carbondale to earn her B.S. in Plant Biology and Ecology. She plans to pursue a career in restoration/conservation. In her free time Leah enjoys sketching, hiking, swimming, and hanging out with her friends. Bios written by the individuals. Filling our backpack sprayers with herbicide before heading into the field. Once in the field, we line up and walk transects across each prairie planting searching for invasive weeds to spray. Picking violet wood sorrel (Oxalis violacea) on a remnant knob. This little prairie flower produces a seed close to the ground so spotting it can be difficult.

By Mary Meier What do 400 hours of volunteer stewardship, $7,000 in donations, and 100 hours of social media posts have in common? They are all components of the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation’s Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program.

The Foundation encourages increased local support and participation in the care of habitat by providing grant funds as a match to local dollars raised and labor donated. Friends of Nachusa Grasslands has been approved for grants totaling $32,000 if we fulfill requirements under several categories:

Friends chose Nachusa’s Orland Prairie, a prairie remnant on the west end of the Big Jump Unit, for its habitat restoration project site. Volunteers have already begun attacking the 23-acre parcel that is heavily infested with the invasive shrub autumn olive. Non-native honeysuckle is also rampant in the area. Mike Carr, Orland Prairie volunteer steward, who has been working on the unit for several years, says, “I really enjoy brush clearing, especially the nasty stuff.” Both autumn olive and honeysuckle are some of the most tenacious foes that Nachusa’s volunteers battle. According to The Nature Conservancy, “Autumn olive is quickly becoming one of the most troublesome shrubs in central and eastern United States. High seed production, high germination rates and the sheer hardiness of the plant allow it to grow rapidly.” In addition, a University of Illinois extension website says, “Controlling bush honeysuckle is vital to the preservation of native ecosystems in Illinois. Bush honeysuckle currently poses one of the greatest threats to forest ecosystems in Illinois.” Saturday workday crews and individual volunteers are using herbicides to kill the woody brush invading Orland. Later this year and early next year, we will over-seed the area with native species collected during the harvest season, conduct prescribed burns, re-contour unsightly gravel pits, and remove non-native trees and large debris from fence rows at the site. Our long-term goal is to establish a diverse prairie planting on the 23-acre site, providing for long-term weed management and suppression of non-native shrubs and trees. Ongoing stewardship efforts, including volunteer labor, herbicide application, and controlled burns, will gradually help integrate the target area into the surrounding habitat.

How can you help Friends earn the stewardship grant? Volunteer for a Saturday brush clearing workday at Orland Prairie — the next one is on June 9. During the summer and fall, you can also help collect prairie seeds for Orland from the preserve. The Friends Social Media Team uses Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and our website to promote volunteer opportunities.

You can also follow Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation’s Community Stewardship Challenge Grant Program on Facebook and Twitter to learn more about the Foundation. Yes! Spring fire season is here! As a Nachusa Grasslands’ fire crew member, it is time to get ready. The Nature Conservancy has three fire crew requirements:

Nachusa Grasslands held its 2018 Refresher exercise on March 10. Folks fresh out of S-130/S-190 attended, along with the regular, seasoned crew. Whatever the team member’s experience, the refresher has always been a day where we all take away lessons. First task of the day — Field test. It helps to take the test in a group. Camaraderie is regenerated as we chat and laugh. Those of the crew who benefit from being taller help those of us who are shorter by setting the pace of four miles per hour. This portion of the day has been nicknamed the “pack test” by Nachusa’s fire crew. Do we call it the pack test because something unconsciously wonderful occurs during the hike that helps reinforce communication and cohesiveness that a crew will need during an actual burn? Are we working together similar to a wolf pack, thus, a “pack” test? Hmm. Next — Classroom. This is the time to review our various burning methods and first aid/safety. This portion of the day is perhaps the most difficult because we all prefer to be outdoors. There is the benefit that someone typically brings homemade goodies to share. Finally, we head outdoors to practice! We split into groups and work through various stations.

Equipment Review. If you have ever burned somewhere else, you immediately appreciate the plethora of tools available at Nachusa. The trucks with large water tanks are helpful. The trucks are not as maneuverable as a utility vehicle (UTV), but the big tanks are great because large volumes of water are available on the fire line. In contrast to the trucks, we have UTV’s with smaller water tanks that can access tight or muddy areas. You can imagine this luxury if you have hauled a water backpack onto a fire line. The trucks and UTV’s are only a sampling of Nachusa’s equipment. Of course, equipment requires preventive maintenance. Before every fire, all vehicles and tools are inspected for common issues. For example:

Vehicle Extraction. The best way to to avoid pulling a vehicle out of the mud is to not get it stuck. Ah, comedian. Truly. . . we talk about being mindful of the terrain, when to have a vehicle in low versus high, four-wheel drive versus two-wheel, and differential lock or not. Then we simulate a stuck vehicle and practice using the new winches on the UTV’s. The new winches are nifty because they have a “remote” that you plug into the anchor vehicle and therefore operate the winch at a safer distance from the vehicles. With this method, you can get a better perspective of the extraction process and know more quickly if the mired vehicle is clear of the mud. Cool. Vehicle backup. We use the trucks for this station. When the trucks are loaded with the water tanks, hose reels, and water pumps, it is difficult to see behind the vehicle in order to back up safely. It is extremely important to have a spotter to help back up without incident — property damage or, worse, personal injury. Verbal communication and clear hand signals are necessary between driver and spotter. We practice making a straight-on backup, and then also a straight-on backup with a 90° turn — all between cones! Yikes! Spot Fire Simulation. By far, the most anticipated station of the day — working with fire! Our burn boss, Bill Kleiman, sets a fire in the prairie and radios a “spot fire” to the waiting crew, asking for resources. We respond, separately attack the fire flanks as two teams, and extinguish the spot fire as quickly as possible, always mindful of safety. The exercise is intended to remind us how to actually approach an unwanted fire, and how to quickly and purposefully move to extinguish the fire before it is out of hand. In speedy succession, we think about the crew member up front working the fire hose and “eating some smoke” — might that person need relief? Can the driver see through the smoke? Is the now blackened area cool enough to drive over? Is somebody tending the hose so that it does not catch on fire? What is the wind doing and how is the fire moving? What type of fuels are we in? Is the fire out with the first pass or do we need more resources? Is the fire completely out? Any flare ups — double check, double check, double check. We gather for our “after action” review; what was good and what could we have done better? Let’s do another! When our refresher exercises are complete, we head back to the Headquarters Barn for some snacks, beverages, more camaraderie, and end with the feeling of a day well spent. I love the whole burning process — from initial preparation to the actual burn — to witnessing the various habitats rejuvenate and thrive following the burns. Do you want to be a part of prescribed fire? Contact us, and we hope to see you on the fire line soon! This blog post was written by Gwen D., a volunteer steward at Nachusa Grasslands.

Autumn has always been my favorite season. Oaks are my favorite trees. So, it seems fitting in "Oaktober" to write about oaks and oak woodlands At Nachusa Grasslands and other places in the Midwest, we are trying to restore the health of our oak woodlands. And really, our region is defined by the oaks. The Nature Conservancy calls our eco-region “The Prairie-Forest Border” between the grand prairie to the south and the mixed woodlands in neighboring states to the north. The area was historically maintained as prairie intermixed with oak savanna and woodlands by Native American nations. Natural plant and animal communities of the region were a direct result of Native Peoples’ use of fire on the land. Without fire, in “The Prairie-Forest Border,” the amount of rain we receive would have yielded dense forests. Many botanists have defined the various intergrades between savanna, open woodland, and closed woodland by the level of sunlight and density and species of trees. (See https://oaksavannas.org/) Today, much of our Illinois woodlands have become too shady to allow sun-loving oaks to grow. Shade is the enemy of oaks. Acorns in shade will not thrive after germination and the limbs of oaks will also die if shaded. How can we tell if the “woods” we are looking at was historically savanna or naturally shady? The presence of large, old oaks with limbs that stick straight out (or used to, but are dead now) indicate the area was likely savanna. An oak growing in full sun without other trees close by will grow limbs horizontally. Oaks that grow close together grow their limbs vertically to reach the sun. To give the oaks a fighting chance modern prairie restorers make use of controlled burns, as well as actual removal of invasive trees growing under and up into the limbs of the old sentinel oaks. We also remove the non-native bush honeysuckle (and other non-native shrubs) from the understory. Our region’s historic mixture of prairie interspersed with woodland types — from dry to wet, from open to somewhat shady — had an enormous species diversity of understory flowers, grasses, and native shrubs. If action is not taken by restorers, the result is a mud forest floor, impenetrable understory with honeysuckle bushes, and an overstory of dead oaks. Elms, maples, and other shade-loving fire intolerant trees move in to take the place of oaks and hickories. This combination of a solid thicket of invasive honeysuckle and loss of oaks gives hardly any habitat for animals. For example, deer and turkey dislike maple and elm, but they love acorns! Native oak-hickory savannas and woodlands in the region are disappearing along with bird species that depend on the open structure: red-headed woodpeckers, great crested flycatchers, and eastern bluebirds. Native wildflowers such as kitten tails, wild hyacinth, prairie lily, and starry campion along with grasses such as bottle brush rye, woodland brome, and long-awned wood grass will not grow in heavy shade. And there are the native shrubs: hazelnut, American plum, hawthorn, and Iowa crabapple! None of these tolerate shade either.

I encourage you to read up on oak woodlands, then take a hike. Explore the Stone Barn Savanna and see how we are doing. It’s a work in progress and sometimes messy, but we see the native oak savanna dependent plants and animals are thriving. Here are some great websites that discuss oak savannas: Pleasant Valley Conservancy—Oak Savannas Last of the Oak Savannas Survive in Minnesota What is an Oak Savanna? Written by Susan Kleiman, a Nachusa volunteer. Since May, the seasonal crew has been working hard at killing and removing invasive plants from the prairie including white and yellow sweet clover, birdsfoot trefoil, king devil, bouncing bet, and reed canary grass. We started the year walking transects back and forth through the prairie plantings like a militant marching band, carefully spot-spraying each invasive species with a selective herbicide from backpack sprayers. Eventually, the herbicide can no longer kill the targeted plants before they produce seed. Then we switch to hand pulling each plant and carrying them out of the prairie in barrels. This prevents the invasive seed from falling back into the soil, causing problems for future crews. Once the plantings have been swept relatively clean, we slowly drive the trails in small groups, “weed cruising” for the few weeds that were missed during our regular, methodical sweeps. By August, the weed season on the prairie has ended. While it requires painstaking effort to manage hundreds of acres, our methods are working. The invasive populations that once riddled many of our older plantings have been greatly reduced. Seed collecting, an important aspect of restoration, takes place throughout the year. This provides a species-rich, diverse ecosystem. Species diversity encourages a more stable food source for creatures such as insects, bugs, and birds. Last year, the crew’s goal was to plant 103 acres of prairie, Nachusa’s largest planting to date. This year, our goal is to plant 83 acres of diverse habitat ranging from a woodland/savannah border to prairie to more mesic and wetland habitat. However, that doesn’t mean the crew is collecting in small quantities. Thus far we have broken the record for the amount of seed collected in a given year for 17 species! To manage these large, high quality plantings, many days involve a grueling grind of trekking through dense vegetation in the blazing sun and humidity, our socks and pants soaked from the morning dew. For breaks, the crew take refuge at headquarters or in the airconditioned bunkhouse basement. Popsicles, sunflower seeds, and other salty snacks fuel us between meals. This year we were lucky enough to have some dedicated volunteers regularly joining the crew, giving our efforts a huge boost! The expertise of the stewards’ immaculate plantings have fueled our motivation and their expertise exemplifies the knowledge the crew strive to attain. The stewards have been a huge help with plant identification and recommendations of seed species to collect, and they have fantastic seed sources. In return, when the stewards have called for help, the crew has acted as reinforcements in the attack against weeds. The crew also found time to work on side projects which promote better efficiency. We built two 3’ tall, 4’x20’ raised beds for prairie violets and other small species that are hard to collect in large quantities. The hope is that weed management in these beds will be easier than a ground weed mat. It also affords the plants protection from predating ground squirrels. Also, we have begun converting a shed into a seed milling shed, providing future crews more space in which to collect more seed, dry it more quickly, and mill it faster. Phil and Kaleb have returned to NIU as full-time students, and Sandra became a part-timer; therefore we have brought on two new crew members. Daniel Crosby, from Rochelle, has been volunteering with us two days a week since July. Nate Scott, from New York, is experienced in a variety of restoration techniques.

The crew members that have been here longest — Avery, Cody, Nathaniel, and Sandra — will be taking turns as crew leader for the rest of the year. Next time you see one of these energetic young faces, be sure to give them a high five! Written by Kaleb Baker, Nachusa's Crew Boss. |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed