|

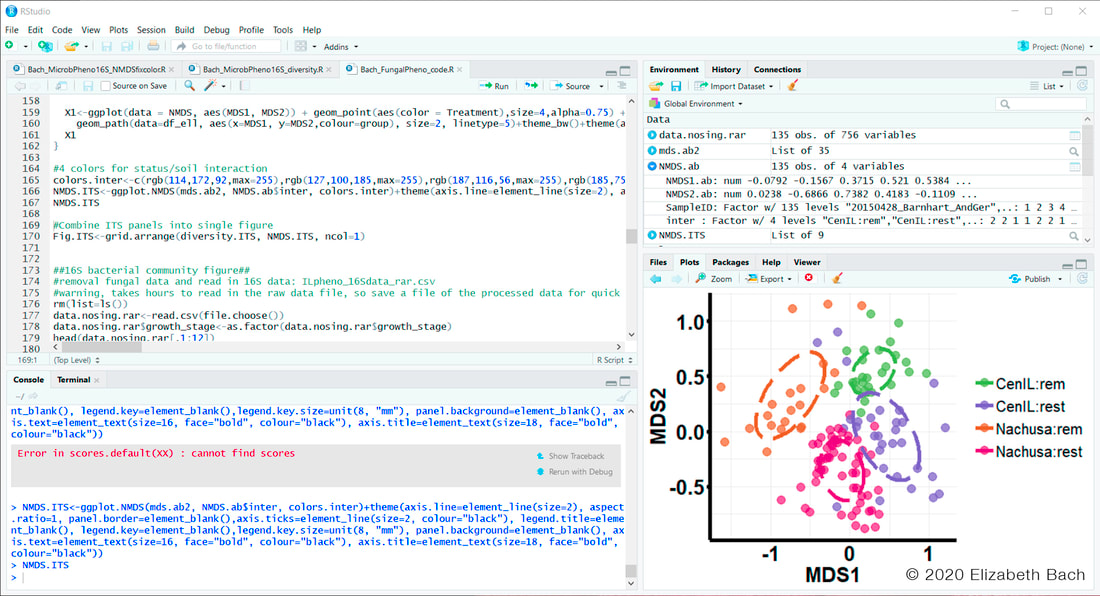

By Elizabeth Bach Ecosystem Restoration Scientist It’s a chilly, rainy spring afternoon, and I sit in front of the computer. Yet I can feel the heat of a sticky August afternoon, hear the whine of cicadas, and see the golden blooms of sunflowers. Mentally, I’m systematically walking through the prairie, carefully identifying all the plants. At Nachusa, many of us, myself included, find working outside in the prairies, savannas, and wetlands most rewarding. However, there is an incredibly important part of conservation work that happens at the computer: data entry and analysis. As the staff scientist at Nachusa, one of my primary duties is to analyze and share data. My primary tool for this work is a free program called “R.” In R, I can manipulate data, produce graphs, run statistical tests, and even produce a final report. Analyzing these data helps everyone at Nachusa refine restoration practices, inspires new ideas, and deepens our knowledge of the habitats and the organisms that live there. Sharing these data in presentations and publications allows us to share lessons learned and best practices used at Nachusa with others in both the conservation and scientific communities. In turn, we also learn from data from other sites. At Nachusa we are lucky to have several scientific researchers working at the site, who collect, analyze, and share data with us. We also have some data, collected over the years by The Nature Conservancy staff and collaborators, which haven’t been analyzed and shared. A key goal for Nachusa is to analyze these legacy datasets and share them. All this brings me back to my computer on an early spring afternoon. When there is less work to be done outside, I’m busy working with datasets on the computer, building graphs, thinking through which metrics best represent the observations made on the prairie, and building statistical models to understand how the Nachusa ecosystem has changed and how it might continue to change into the future. All this work is done with a few lines of code on the computer. While very different from the outdoor joys and challenges of data collection, there are both joys and challenges with this work. I often think of data analysis as a mystery to solve. What will the data show? What will I learn? How might this challenge or confirm observations from other scientists in other places? Every dataset is a new adventure, and I find a sort of excitement in that. It can also be frustrating. I spend a lot of time finding and correcting mistakes. There is no travel guide to inform my decisions. Fortunately, I can work with collaborators as travel buddies on these adventures, to bounce ideas off them, and gain a new perspective. One of the joys of working at Nachusa is being at the intersection of many paths of scientific research and natural history observation. Working with people with different expertise, skills, and perspectives deepens my understanding of science, the tallgrass prairie, and Nachusa. Elizabeth Bach is the Ecosystem Restoration Scientist at Nachusa Grasslands. She works with scientists, land managers, and stewards to holistically investigate questions about tallgrass prairie restoration ecology.

1 Comment

By Angie Burke Volunteer Coordinator, The Nature Conservancy We are all familiar with the saying “It’s the little things that matter”, and it’s the management of the tallgrass prairies at Nachusa Grasslands that has made a big difference for the littlest of things— mammals. Our paper “Early Small Mammal Responses to Bison Reintroduction and Prescribed Fire in Restored Tallgrass Prairies”, coauthored with Dr. Holly Jones and Dr. Nick Barber, sheds light on how the varying management of prescribed fire, coupled with the reintroduction of grazing bison, has created a habitat haven for the small mammals in a mix of agriculture and rural development.

blocking our safe access to a site, to capturing meadow jumping mice awakening from their winter slumber, every sampling season held a new adventure for us. Some of the little buddies we captured and released were deer mice, white-footed mice, prairie voles, northern short tailed shrew, meadow jumping mice, harvest mice, and my favorite, the 13-lined ground squirrel. Rain, snow, or shine, the little buddies are welcomed to the study each season with excitement by the many stewards, volunteers, and scientists that call Nachusa home. In the first two years since bison were reintroduced, we found fewer small mammals in older sites relative to new restorations and fewer as time since fire increased. Additionally, there was a higher diversity of what we did document in those older sites and slightly lower diversity (fewer than one species, on average) in sites where bison were present. This difference was driven mainly by prairie voles; fire removes litter and residual dead vegetation which is important habitat for voles. The overall abundance was especially influenced by the deer mice, which are able to use the areas with a higher prevalence of bare ground associated with frequent/recent fire on the landscape. Overall we found that bison reintroduction had fairly weak impacts to small mammal communities in the first few years. Bison, when reintroduced at a relatively low stocking rate, are not likely to cause significant shifts to this community or, by extension, to the seed predation and dispersal functions they serve in prairies. The many different types of habitat created by the managers at Nachusa varying prescribed fire with grazing bison maintain the diversity of small mammals on the landscape scale. Continuing to document the changes in the small mammals through time, while capturing the changes with other animal, invertebrate, and plant composition, will help to show how the little things matter on a big scale when it comes to tallgrass prairie restoration.

By Jess Fliginger In 2013, Dr. Holly Jones started conducting a long-term research project at Nachusa Grasslands on quantifying the effects of disturbance-related management strategies on small mammal populations at restored and remnant prairie sites. The reintroduction of bison in 2014 allowed for a powerful before and after bison impact study that documented the effects of bison grazing on the small mammal communities. Data collected on species responses to bison, prescribed fire frequency, restoration age, and vegetation composition will inform decisions regarding abundance and biodiversity for small mammals. Small mammals play important roles in the food web by influencing vegetation structure through herbivory and seed predation, as well as serving as prey for predator species. So far, plant communities with bison grazing are becoming more diverse and more abundant with small mammals. In the beginning, Dr. Jones ran the small mammal project by herself for a year until she was able to pass it on to her Master’s student Angela Burke in 2014. It was quite a challenge to run the project on her own, and volunteers have become an essential component to keep it going. Over the years, we have had more than 100 volunteers participate to help check traps in the morning and reset traps in the afternoon. On the first day of small mammal trapping, or as we like to call it “smammaling”, we prep 150 metal Sherman traps by baiting them with peanut butter and oats. Our small army of volunteers, 3 or 4 people, create an assembly line, with one person spreading just a dab of peanut butter on the backplate and the other sprinkling a small pinch of oats inside. Once all traps have been prepped, we start stacking rows of them, Tetris style, in the back of Scarlet, our NIU mule.  Out of the four seasons we sample for small mammals, August and October have the tallest vegetation, making it difficult to locate our poles. We flag the highest plant we can find nearby; for me it’s usually prairie dock or good ol’ big bluestem, and we try to navigate our way through the meandering paths of the tallgrass prairie jungle." We take off to set 25 traps at six of our 5x5 grid sites, hoping our plans don’t get foiled by any bison delays or strange weather. Each site has flagged poles to indicate where the trap must be set; however, finding them can sometimes be a challenge. Bison love using our poles as backscratchers, and they are often found sprawled across the prairie. At each pole we place an open trap where it will sit until an unsuspecting critter passes by and catches a whiff of irresistible Jif.  The mice spend the night at their “mouse hotel” feasting on peanut butter and oats until we are back to process them in the morning. I always get a rush of excitement as I walk up to a trap and notice the door is closed. When I peek inside the trap, I am usually able to see a little face staring back at me. Occasionally, I’ll get a trigger-no-capture and my excitement will fade to dissatisfaction. Likewise, thieves are a constant problem. Some especially small, speedy daredevils are able to run in to the trap, take some quick bites of peanut butter, and run out without triggering it. We keep tabs on which traps have been thieved and adjust/replace them accordingly. To process the small mammals, we record the weight and take measurements on the right hind foot, tail, and body using a caliper. In addition, we determine their sex, age, reproductive status, species, and PIT tag number. Some of the species we have captured at our sites and record data on include thirteen-lined ground squirrel, deer mouse, white-footed mouse, western harvest mouse, meadow jumping mouse, prairie vole, meadow vole, and masked and short-tailed shrews. The most common species we capture is the deer mouse, Peromyscus maniculatus. Depending on whether it’s a new capture or recap, we will carefully insert a PIT tag underneath its skin – similar to microchipping your pet – as a way to keep track of its movements, survival, and reproduction throughout the study. It’s always a treat when we have an overwinter or recapture from the previous year; they were the lucky ones to survive the long cold winter! Finally, we provide complimentary haircuts to all new buddies and collect the hair to run in the stable isotope lab. The information gathered from each sample result can tell us about their diet and role in the food web. Since 2015, I have been volunteering with Dr. Jones’ small mammal project. This year I was given the opportunity to help run the project and process the small mammals until her incoming PhD student, Erin Rowland, arrived. I took up the challenge, and with practice I became a pro. I would say my favorite part of the job is meeting the volunteers and training them how to be great smammalers. I enjoy acting as a Nachusa tour guide to all newcomers, young and old. Although anyone is welcome to volunteer, the majority of our helpers are undergraduate students who enjoy a break away from the classroom. Volunteering for the small mammal project gets you to spend time outside, which is beneficial to your health and well-being. It inspires the public to engage in the scientific process, appreciate native plants and animals, and meet others who care about our environment. Furthermore, it helps develop team building skills that are important for any job setting. Volunteers are the heart and soul of the small mammal project, and without them I’m not sure it would be able to persist. There is a lot to accomplish within the 12 consecutive days we are at Nachusa smammaling, and any help is greatly appreciated! If you are interested in volunteering, please contact Erin Rowland. To me, the small mammal project is all about making new and old friends — volunteers and mice alike. Small mammal research has been supported by the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands science grants from 2015 to 2018.

Consider a donation to the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands to support the ongoing science! By Jason Willand, PhD I first visited Nachusa Grasslands in August 2008 while I was working for the Illinois Natural History Survey. I was overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the restorations that comprised the preserve and never envisioned myself conducting research on these restored prairies. As fate would have it, I returned to school in 2009 to start work on my doctorate degree and was able to fit part of my research into the restorations at Nachusa. The research was for the first chapter of my dissertation, where I examined the role of seed and bud banks for plant community regeneration during prairie restoration. The field portion of this work lasted only five days, and afterwards I was hoping that I would have a chance to return to conduct more research. As fate would have it again, I was able to conduct a small research project at Nachusa as I was wrapping up my dissertation in July 2014. The research project was the result of brainstorming between my dissertation advisor Sara Baer and myself. With the imminent introduction of bison on the preserve in October 2014, we wanted to develop a potential long-term monitoring project. We decided that an interesting study would be to examine the resource availability of the remnant and restored prairies before the bison were introduced. Bison were the dominant grazers in the tallgrass prairie ecosystem before settlement by the pioneers. They play a “keystone” role in the maintenance and diversity of prairies because of their wallowing behavior and preferential grazing on graminoids (grasses and sedges). Most bison research to date has been conducted either on private game ranches or remnant prairies, with little research coming from restored prairies. We collected data on three resources that could affect where bison would graze in the introduction area: plant biomass, the forage quality of the biomass, and soil carbon and nitrogen. Knowledge of plant biomass provides a rough estimate of the amount of plant matter available for bison consumption. Forage quality of plant biomass is informative because it not only tells us how much of the plant matter is actually digestible to the bison, but also the fat and crude protein content of the plant matter. Soil carbon and nitrogen are vital because as a plant uptakes them, they allow a plant to produce important macromolecules for growth, such as proteins. In order to adequately sample the bison introduction area we surveyed three different prairie types: remnant prairies, restored prairies more than 15 years old and restored prairies less than 5 years old. To quantify potential differences in resource availability between the three prairie types we collected plant biomass and soil samples from three different “fields” in each prairie type. Both the plant biomass and soil samples were returned to the laboratory at Southern Illinois University, where they were processed. Forage quality samples were sent to the University of Wisconsin Madison Soil and Forage Laboratory for analysis of seven components of forage quality. We found that the restored prairies less than 5 years old had almost twice the amount of plant biomass compared to the restored prairies more than 15 years old and more than twice that of the remnant prairies. Surprisingly, there was little difference in forage quality and stored carbon and nitrogen in soil among the three prairie types. The similarity in forage quality between the three prairie types may be attributed to prescribed burning, as all the fields were burned in April 2014 three months before we sampled them. Prescribed burning has been found to increase forage quality for up to a year after a fire and may have created homogenous plant biomass on the landscape. We expected soil carbon and nitrogen to be higher in the remnant prairies because these soils have not been tilled, a disturbance that has been found to reduce the storage of carbon and nitrogen in agricultural soils. The remnant prairies we sampled perhaps had a lower storage of carbon and nitrogen than expected because the soil was fairly shallow in comparison to the typical deep, loamy soils that characterize many remnant prairies. The findings of this study suggest that bison may prefer the youngest restored prairies because there is simply more plant biomass available and little difference in the forage quality from the other prairie types. Even with these preliminary data it is still difficult to predict where bison will graze. Other factors that need to be considered are the dietary preferences of male and female bison and how prescribed burning creates a more heterogeneous landscape in the three prairie types. Post-introduction data have not been collected, so at this point any predictions of landscape use by bison is speculative at best. Maybe fate will strike again and I will be able to collect more data at Nachusa sometime in the near future. Jason Willand is an associate professor of biology at Missouri Southern State University in Joplin, MO where he currently serves as the assistant department chair and chair of the conservation section of the Missouri Academy of Sciences.

By Jenn Simons Nachusa Grasslands Science Extern On January 10th, 2019 I made a simple phone call to Nachusa Grasslands. Four months later, I was packing up my things to spend the summer living 480 miles east of my hometown. And with that, this Nebraska native ended up in an eastern tallgrass prairie state of both mind and place.  Jenn Simons Jenn Simons Prior to that fateful January day, as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison I had narrowed down my research interests to the impact of conservation grazing on vegetation in midwestern prairies. My goal was to meet the requirements of my degree with a research project at the intersection of stewardship and applied ecology. Though the importance of disturbance to prairie management is well known, grazing on restored and remnant prairies has been a contested issue. Additional data to understand some of the trade-offs to using grazing for land management facilitate better understanding and application of the tools available in a land manager’s toolbox. The only thing that I was missing to begin my research was access to a herd of conservation grazers (nothing too significant, right?). During my quest to connect with folks using grazing as a land management tool in prairies, I ended up on the phone with Dr. Elizabeth Bach at Nachusa. As many of you know, it’s hard not to fall in love with a site as beautiful and biodiverse as Nachusa Grasslands. It’s even harder not to fall in love if that site also features a herd of grazing animals and the existing infrastructure to study their impacts. After my first conversation with Dr. Bach, I was sold. Nachusa was where I wanted to be, and the impact of their bison was what I wanted to study. In my case, and the case of many other grad students, there’s a gap in available funding between spring and fall school semesters. Grants and assistantships don’t always pan out, and many degrees in ecology require a large amount of data collection during the summer months (something rather at odds with working full time). Fortunately, 2019 marked the first summer for a Science Extern position at Nachusa. Open to all graduate students currently or beginning to conduct research specifically at Nachusa, the externship was to be awarded as an external grant to the student’s home university and paid as a salary, allowing the student to remain enrolled and continue receiving benefits. Just as the crew of seasonal employees spends their week supporting land stewardship needs throughout the summer, the role of the science extern was to support data stewardship needs throughout the summer. This position continues Nachusa’s history of encouraging research and providing opportunities for budding conservationists. With my fingers crossed, I submitted my application for the position and tried not to get my hopes up. I made a mental plan B (and C and D) for how I might be able to make my Nachusa research dreams come true if my application wasn’t successful. Work full time and collect data on the weekends? Take out loans? Choose a simpler research question? These are questions most grad students have had to seriously consider at some point. When sites like Nachusa are able to offer summer positions that merge science with practice, both the student and the site benefit from the results. Much to my delight, plan A came through, and I never looked back. Since May I’ve been assisting in collection, entry, and analysis of core ecological data for Nachusa while simultaneously collecting my own data. To answer my research questions, I’m leveraging twenty-two fenced plots (10mx18m) replicated across habitat types in the 1,500 acres of bison habitat that were designed and built by Bill Kleiman, Cody Considine, TNC staff, and collaborating scientists prior to the introduction of the bison in 2014. As opposed to keeping something inside a fenced in area, these fenced plots function as “exclosures” and keep bison outside the fenced area. Building on plant community data taken in 2014-15 and 2017-18, I’m collecting additional data to compare changes in the vegetation diversity, structure, and abundance along with soil compaction between grazed and ungrazed land over time. With the mentorship of Dr. Bach and my advisor, John Harrington, these data will be analyzed and contribute to both the advancement of my degree and the understanding of how bison have impacted Nachusa’s vegetation. In addition to the various science program tasks, opportunities abound to participate in stewardship activities and learn more about careers in ecology outside of academia. I’ve gotten to track Blanding’s turtle, set traps for small mammals, participate in evening moth surveys, observe rare plants in their natural settings, improve my R coding ability, utilize ArcGIS to create new maps, collect seeds and control weeds with the seasonal crew, and talk with highly knowledgeable volunteer land stewards. I can honestly say there’s no place I’d rather be this summer than at Nachusa Grasslands, and I’ve already become a better ecologist as a result.

By Leah Kleiman Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) is a perennial shrub native to temperate Asia and is invasive in the Midwestern United States. It now infests many savannas and woodlands and is difficult to eradicate. Bill and Susan Kleiman and I are co-authors of a study recently published in the journal Ecological Restoration, titled “The Successful Control of Lonicera maackii (Amur honeysuckle) with Basal Bark Herbicide” (http://er.uwpress.org/content/36/4/267.full.pdf+html). Our study looked at the efficacy of basal bark application, where a mineral oil solution of herbicide is sprayed in a 6-inch band on the bark without cutting the plant. Our study found 100% mortality with basal bark treatment. A variety of other treatment methods are used to battle honeysuckle. Manual pulling works well on small individuals in soft ground, but becomes impossible with larger sizes. Cutting and treating the stumps with herbicide is effective, but very time-consuming. We recommend the cut-and-treat method for sensitive high-quality areas. A foliar spray of herbicide is effective and efficient, but will have much more off-target damage and can only be used in the growing season. Fire is a useful tool in keeping brush at bay, but it will only top-kill shrubs. The basal bark method is efficient, effective in all seasons, and has minimal off-target damage. Some things to keep in mind: 1) Re-treating is important for success. One treatment is not enough. Some shrubs will inevitably be missed, and yearly recruitment will occur until the seedbank is exhausted. 2) Honeysuckle treated in the dormant season may still leaf out and die later in the growing season. So if you notice this, it does not mean that your treatment has failed, but rather that you need to check back at a later date (typically late summer/fall). Our study concludes that basal bark treatment paired with regular fire is the optimal way to eradicate honeysuckle invasions. For more information on treating honeysuckle with basal bark, see the February 3, 2019 blog post “A Study on Controlling Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii)” by Kaleb Baker.

By Kaleb Baker

Amur honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) is an invasive shrub that flourishes along forest edges and in open woodlands such as those at Nachusa Grasslands. Amur honeysuckle shades out native flora with its early leaf-out and prolonged leaf retention, and when left uncontrolled, can produce a near monoculture, threatening biodiversity.

Land stewards everywhere have implemented a variety of different eradication methods, including hand pulling, cut-and-treat with herbicide, foliar-applied herbicide from backpacks or helicopters, basal bark herbicide treatments, and prescribed fire. Continuous treatments and monitoring are needed to eradicate Amur honeysuckle, making the cost, effort, and time requirements of controls important.

Knowing the efforts we go through to manage honeysuckle, as well as the amount of conjecture surrounding the best practices, I worked with my advisor Dr. Nick Barber to study how effective basal bark treatments and prescribed fire are at controlling honeysuckle., I decided to study how effective basal bark treatments and prescribed fire are at controlling honeysuckle. Basal bark and fire are regularly-used control methods at Nachusa. Basal bark treatments involved spraying a 20% solution of triclopyr herbicide around each plant’s base from a backpack, which was both quick and easy. In this study I included 800 individually-marked Amur honeysuckle at 5 different sites within Nachusa Grasslands and Franklin Creek State Natural Area. Basal bark treatments were applied in fall 2017, winter 2018, early spring 2018, and late spring 2018 to see if the season of application affected the mortality of honeysuckle or the extent of damage to non-target flora. Prescribed fire was administered to half of each of the 5 sites in spring 2018. I then checked mortality in the early fall of 2018 to allow the honeysuckle time to either drop its leaves and regrow them (falsely dead) or to retain its leaves for an extended period of time before dying (falsely alive).

I found that basal bark applications were equally effective at killing Amur honeysuckle, regardless of treatment timing. The combined mortality rate of herbicide treatments was 98.4% across all herbicide treatment seasons, compared to a 2.5% mortality with no basal bark treatment. Prescribed fire did not impact mortality positively or negatively.

I also placed a 1m2 quadrat around 200 Amur honeysuckle to measure off-target damage to the plant community in spring 2018, finding a decrease of living cover equating to about a 10-inch radius. The off-target “ring of death” did not differ based on fire treatment or basal bark season.

I was lucky to receive a grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grasslands where I will be able to return in May 2019 to resample the off-target vegetation quadrats to evaluate how quickly the flora recover from the various treatments.

From my current results, I highly recommend using basal bark treatments to control Amur honeysuckle for all but the highest quality of areas. The speed and ease of use allow managers to cover large swaths of invaded areas across fall, winter, and spring seasons. The standing dead material from the honeysuckle can be reduced with a masticator or brush mower in the non-growing season or with regular prescribed fire, which should be implemented anyway.

Kaleb Baker is a Master's Candidate at Northern Illinois University, focused on natural areas management practices, and current Stewardship Committee Chair for Franklin Creek Conservation Association.

By Dr. Elizabeth Bach, Ecosystem Restoration Scientist December 5 is World Soil Day, a time to recognize the vital role soils play in our ecosystems and health: growing food, filtering water, recycling air, mitigating climate change, and supporting more than 25% of all biodiversity! Soil is the foundation of prairie restoration at Nachusa Grasslands, the starting point of a prairie planting. There are many questions about how soils impact prairie restoration success and how prairie restoration affects soils. Today, we highlight a few of the soil-focused scientific studies that have been conducted at Nachusa Grasslands:

Question: Do communities of soil critters like earthworms, ants, ground beetles, centipedes, millipedes, and spiders change during prairie restoration? Answers: Prairie restoration increases the number, abundance, and mass of soil critters like earthworms, ants, centipedes, and spiders with time since planting. Interestingly, different prairie remnants, even within the Nachusa preserve, have very different communities of soil invertebrates, and it’s difficult to know what a typical remnant invertebrate community may look like. Wodika & Baer 2015. If we build it, will they colonize? A test of the field of dreams paradigm with soil macroinvertebrate communities. Applied Soil Ecology 91:80-89 Wodika et al. 2014. Colonization and recovery of invertebrate ecosystem engineers during prairie restoration. Restoration Ecology 22: 456-464 Ground beetles show a different pattern, with high numbers of species and abundance in young plantings. Although older plantings had lower species richness, the roles those species play in the ecosystem diverged, indicating that older plantings support stable, diverse beetle communities that fill multiple roles in the ecosystem (e.g. different sizes, active at different parts of the day/night, eating different things). Barber et al. 2017. Species and functional trait re-assembly of ground beetle communities in restored grasslands. Biodiversity and Conservation 26:3481-3498 Question: Do soil microbial communities change during prairie restoration? Answer: Older restorations at Nachusa host microbial communities that are distinct from younger plantings, and that more closely resemble remnant communities. A couple of the key bacterial groups distinctive of prairie remnants and older restorations are Verrucomicrobia and Acidobacteria. The next question is to learn more about what those bacteria do! Barber et al. 2017. Soil microbial community composition in tallgrass prairie restorations converge with remnants across a 27-year chronosequence. Environmental Microbiology 19: 3118-3131 Question: How does plant diversity impact ecosystem functions like soil carbon and nitrogen cycling? Answer: Nachusa’s high plant diversity restorations had more roots, more microbial mass (especially mycorrhizal fungi), more structured soil, and less “leaky” nitrogen compounds that can wind up in water ways compared with low plant diversity restorations in the same area. This is the first study to show that very high plant diversity restoration can lead to improved ecosystem functioning. Klopf et al. 2017. Restoration and management for plant diversity enhances the rate of belowground ecosystem recovery. Ecological Applications 27:355-362 By Ryan Blackburn In the spring of 2013, I had little to no knowledge of tallgrass prairies or the various forms of life they held. I was an undergraduate at the time, and my class at Northern Illinois University had an opportunity to visit Nachusa Grasslands and receive a tour given by one of their dedicated stewards, Jay Stacy. As the class looked out across the beauty rolling over the tallgrass landscape, Jay directed our view downwards at our feet and started naming twenty or more plant species in just a little patch of dirt the size of a laptop. Jay also spoke of the rumors that bison may be coming to the landscape and how they were thought to have the ability to increase diversity of the prairie plant communities which already seemed teeming with life. This was the moment I realized that the tallgrass prairie and plant communities they held were something that I wanted to know more about. After a couple of growing seasons, a reintroduction of bison onto the landscape was accomplished, and my masters research was born. Bison are large animals that require a lot of energy, which mainly comes from one family of plants, the grasses (Poaceae). Due to this selective grazing, bison create open space in their habitats for wildflowers to take root and increase the diversity of the tallgrass prairie overall. At least this is a summary of what had been observed in the research of remnant (never-plowed) prairies west of the Mississippi River which reintroduced bison as well. In hopes to recreate this tale of romance between bison and tallgrass prairies, Nachusa Grasslands reintroduced bison to their preserve of both remnant and restored lands. The question still remained: will their diet in this new area largely be made up of grasses, and how soon would we see changes in the plant communities following their reintroduction? To study this, I looked at both bison diet and differences of plant communities between sites with and without bison over a period of two years. To figure out what the bison were eating, I used a technique called stable isotope analysis on bison tail hair pulled during the annual roundup. This allowed me to find signatures of plants within the bison hair and estimate these plants' abundance within bison diet. Better yet, I could cut bison hair into segments and look for seasonal changes. Through this analysis I was able to estimate major dietary groups of their diet between May 2016 and September 2016. I found that bison were doing what Nachusa brought them here to do: eat grasses (for the most part)! However, in late summer bison started to transition from largely grass species to wetland species and some wildflowers, something that had never been documented before. This was an unexpected shift that may lead to unforeseen consequences to wetlands, but further research is needed to speak to this. Now that we know bison are mostly eating grasses during the growing season, we want to know how this might be impacting prairie plant communities. Attempting to answer this question, I, along with a team of dedicated plant enthusiasts, counted and measured percent cover of plant species across sites with and without bison. I quantified these communities in a variety of ways and compared them to see if bison were driving any differences between the two communities. Even though the bison had only been at Nachusa for three years, there were already evident changes happening within the plant communities. As predicted, areas with bison had more variation within their plant communities and had a higher ratio of native to non-native plants than those sites without bison. Further analysis shows that both variation and native to non-native ratios may be driven by bison preference of certain species such as bluegrasses (Poa compressa and Poa pretensis) suggested by a higher occurrence of these species in sites without bison. The bison of Nachusa Grasslands were reintroduced to do a job: increase the diversity of plant communities. Though my research does not yet see an increase in diversity, it does suggest that bison are starting to go to work eating grasses and changing plant communities around them. Continued monitoring of these communities (especially those tasty wetland communities) is needed to gain a better understanding of bison impacts and how they progress in restored tallgrass prairies. Ryan Blackburn just received his M.S. degree studying bison diet and their role in the restoration of plant communities in tallgrass prairies. Ryan is also looking at grazing impacts on a landscape scale using drone aerial imagery. In 2016, he received a $1,500 Friends of Nachusa Grasslands Scientific Research Grant for his "Determining Bison Diet and Bison Effects on Vegetation in a Chronosequence of Restored Prairie at Nachusa" project.

By Heather Herakovich, MS Birds are known harbingers of spring. Although most stick around during the brutally cold Illinois winter, we don’t take much notice until they are everywhere in our yard, waking us up in the morning and pooping on our cars: spring time! It’s finally springtime, and at Nachusa the birds are singing, vying for territory, and finding mates. These aren’t your typical backyard birds like the American robin and northern cardinal, who are your usual early morning alarm and repeating snooze. Nachusa holds a wide variety of bird species, including some of the ones in the most need of conservation: grassland birds. They come with funny names like bobolink and dickcissel, and in all shades of brown and yellow and sometimes black. Grassland (prairie) birds are declining at a faster rate than most bird species, and a majority of this has been caused by habitat loss. Illinois is the prairie state, but only one hundredth of its original prairie remains. Places like Nachusa are doing their best to restore the agriculture fields and recreate the best prairie as humanly possible. Doing this requires a lot of hard work, hours of picking seed, planting seed, removing unwanted plants, burning portions of the prairie and mowing. The birds seem to be responding to this management fairly well. However, there is an elephant in the room, or shall I say a bison in the prairie. American bison are our national mammal, and rightfully so. These large herbivores used to roam most of the contiguous United States, until they were hunted to near extinction. I’m sure you’ve heard the story. But now they’re back! Grazing is a crucial disturbance in prairie habitat, providing habitat for a lot of species and open space for a lot of plants. But how will birds respond to this large, iconic grazer on its new home in Franklin Grove, Illinois? When I started my graduate degree at Northern Illinois University in 2013, I was able to start trying to answer that question more specifically by looking at how their nests were going to be impacted by bison. Bison can impact bird nests in a variety of ways. There are the obvious negative direct ones like trampling and dislodgement, but there are also some not-so-obvious impacts. These impacts can be either positive or negative and can affect the nesting habitat, nesting material, clutch size, and ultimately the survival of the chicks until they leave the nest (nest success). Seeing if bison are impacting nest success means I must find the nests first. This is the most difficult part. They are roughly the size of a compact disc, made from the vegetation they are in, and wickedly hard to find. If you come by Nachusa early in the morning this summer, I’m sure you’ll see me walking in the prairie, waving around a stick, and waiting “patiently” for a bird to fly from the vegetation. Although difficult, watching these nests through time is a very rewarding experience. I’ve seen nests being built, eggs being laid, chicks hatching, and chicks leaving the nest. Please don’t try this at home, though. Nests are sensitive to human disturbance, and I follow specific protocol to not influence their nest success. Bison don’t seem to be influencing their nest success either, negatively or positively. This is good news. They are one of the main sources of disturbance in the prairie, and it is a relief that they are not trampling nests of birds in decline, at least four years post-reintroduction. Watching these nests is only a part of my graduate research. I am also looking at how bison may influence nest predators, brood parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds, and what bird species are present. So far, I am not seeing anything change enough to be consider a bison impact. Time will tell if there will ever be a noticeable impact of bison on grassland birds. If I were here in ten years, I would try to find out. The beautiful prairie and bison are a great reason to visit Nachusa, but don’t forget about the birds. Sure, they all look similar and are hard to spot, but they are our harbingers of spring and make the prairie sing in the summer. Heather Herakovich is a PhD graduate student at Northern Illinois University. Heather studies grassland bird nest density, nest success, and species composition in restored plots of varying age as well as remnant control prairies. Heather is attempting to quantify the effects of bison reintroduction, prescribed fire, and restoration age on grassland bird populations at Nachusa.

|

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed