|

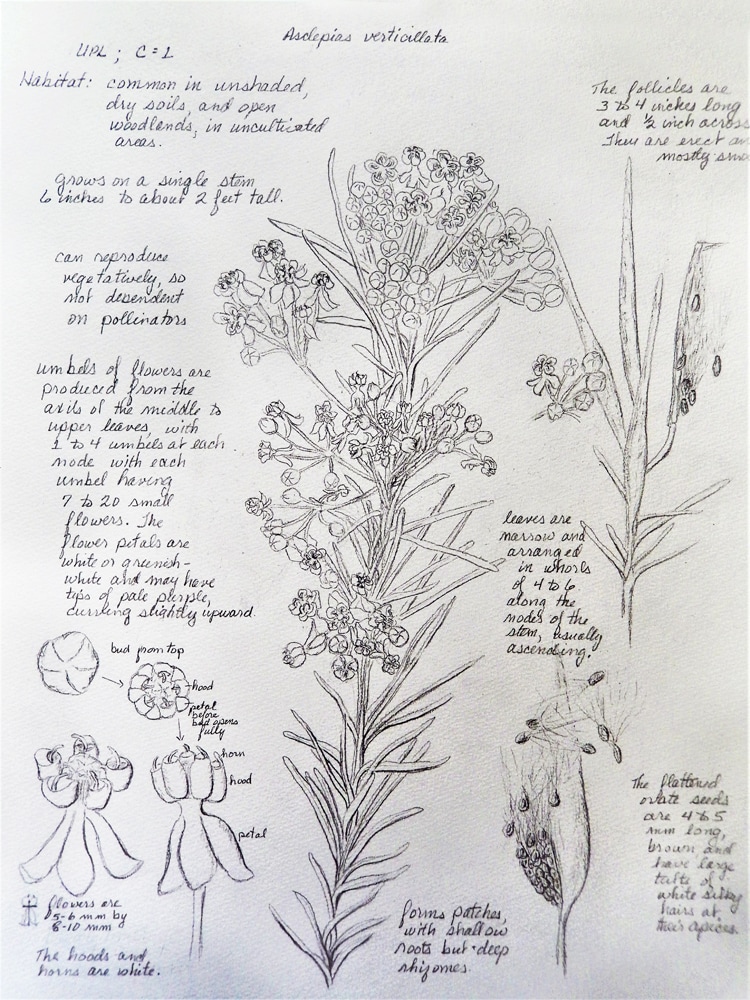

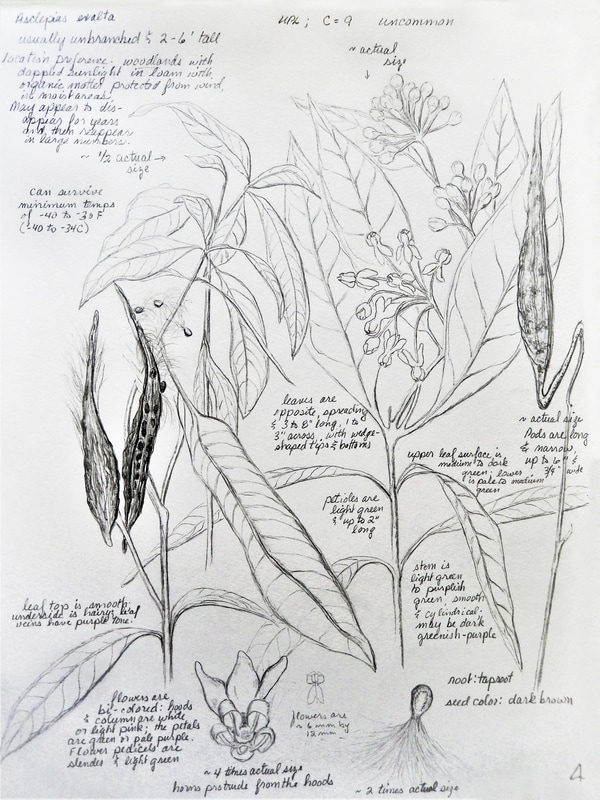

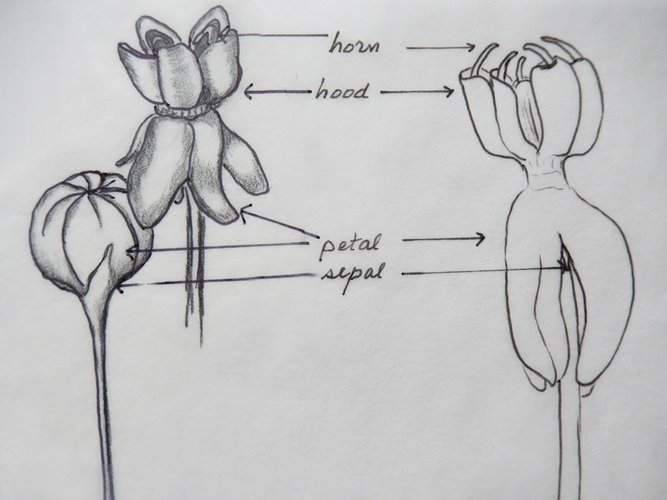

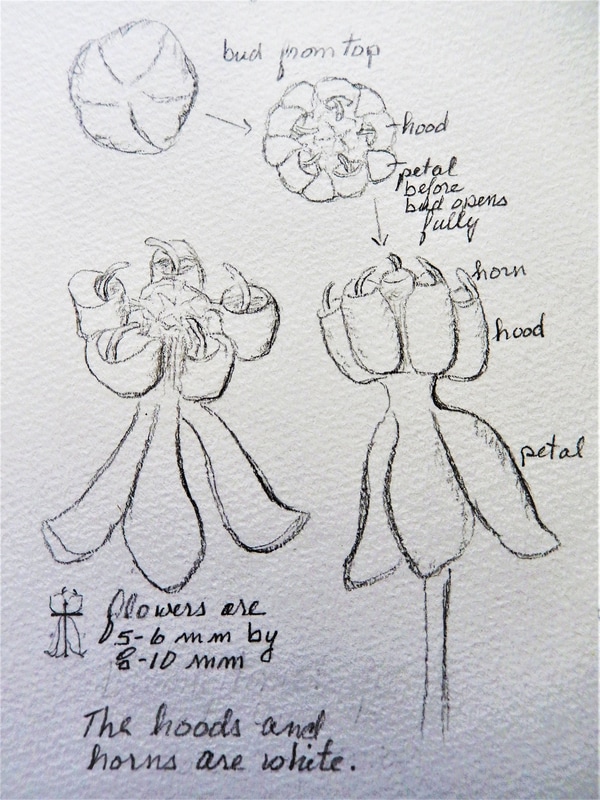

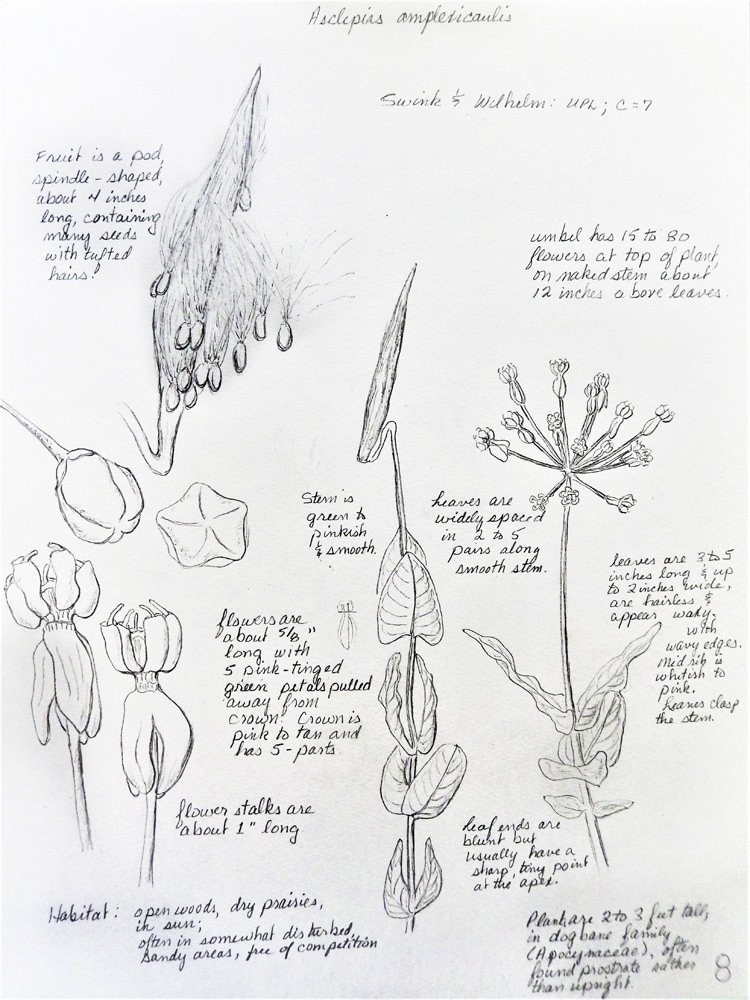

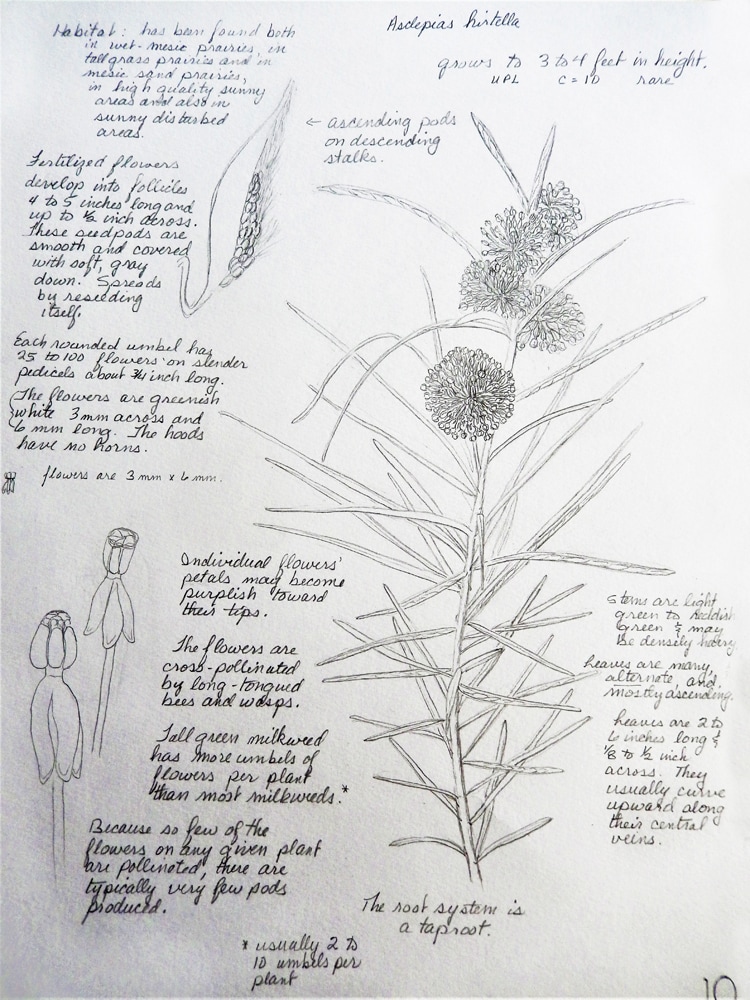

Milkweeds are a subfamily of the dogbane family (Apocynaceae). Most of us are familiar with the extreme dependency of the Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) on milkweed plants. These native perennials are the only plants that Monarch larvae (caterpillars) will eat. If there were no milkweeds, there would be no Monarchs. The Monarch butterfly is Illinois’ State Insect. In April and May, Monarchs begin arriving back in Illinois from their winter migration to Mexico. So, this is a good time to take a quick look at a few of the twenty-three species of milkweeds that are known to be native to Illinois. They are a critical part of the habitat needed by Monarchs. Milkweed is named for its white milky-looking sap, although at least one milkweed species, Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) has a clear, rather than milky, sap. At one time, various species of milkweeds could be seen growing in most any ditch, vacant lot or fence line; hence the unfortunate “weed” in its name, even though this plant genus has some of the world’s most unique flowers. The botanic name for the milkweed genus is Asclepias. The name was chosen for Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, although some milkweed species are toxic. So much for naming . . . Let’s look at milkweeds as a group to see what the various Asclepias species have in common. As we proceed, I will begin pointing out some of the characteristics that distinguish one milkweed species from another. Milkweeds are perennials, generally with leaves in pairs along the stem, or in whorls. The flowers develop in umbels (flower clusters in which all the branches come from a single point). I’ve chosen to illustrate a couple of milkweed species that have fewer flowers per umbel so that it is easier to really see the typical milkweed umbel structure, as well as the paired leaves on these particular milkweed species. Once you are aware of the umbel structure, it is much easier to look for and to recognize it, even on the milkweed species that have 25 to 40 or many more flowers per umbel, or that have multiple umbels. See samples in photos below. Note the slender leaves (about 1 inch wide) of the Swamp Milkweed, as compared to both the Common and the Purple Milkweeds above. The even more slender leaves of the Tall Green Milkweed (slightly over ½ inch wide) are whorled around the stem or alternate, rather than being paired opposites, as is the case with most of our local native milkweed species. Milkweed flowers are one of the most complex flowers in the plant world, probably second only to orchids. This discussion is limited to the most visible flower parts that are useful in identifying these amazing plants and to see how pollen is transferred. The flower structure varies somewhat by species, but they all have a vaguely hourglass shape, with each flower having five sepals (that fall back and become hidden by the petals as the bud opens) and five petals that reflex downward when the bud opens (see sketch above). Most flowers have petals and sepals, but milkweeds are unique in also having a third set of structures just above the petals: five pairs of hoods (where the nectar is) and horns surround the flower column (where the pollen is found in vertical slits there). These hoods and horns are actually modified stamen structures. See the sketches above. The sketch of the Whorled Milkweed shows the flower column that the hoods encircle, the spaces between the hoods and the slits in the flower column. Within the slits, pollinators can encounter the sticky pollen packets through which pollen is delivered to the eggs in the ovary at the base of flower column. In the video below, you can see the orange pollen baskets attached to the bumblebee's back legs; pollen was transferred to these baskets when his legs slipped into those slits in the flower column. Those leg baskets now spread pollen to the subsequent flowers this bee visits. Fertilized milkweed flowers develop seeds in follicles (pods), with each seed having a coma (cluster of silky hairs) which easily carries the seed on the wind. You are likely familiar with the Common Milkweed pods, which are warty with soft spines, and wider at one end than the other, splitting open when the seeds are ready for the wind to work its magic dispersing them. Showy Milkweed has very similar pods as Common. Other species, such as Purple Milkweed, have pods that are similarly shaped, but downy rather than spiny, or, in the case of Sullivant’s Milkweed, are smoother, with projections only on the upper half. Many milkweed species have slender, smooth pods. All have many seeds packed inside, each with its coma. As you can see in the previous and following photos, milkweed flower size, color and precise shape all vary by species. These various species also differ in their habitat preferences, from very dry to very wet, from full sun to wooded areas, from sand to heavy clay, from a preference for disturbed soil to an intolerance for it. The following four species are local native milkweeds that are relatively easy to find if you are interested in seeing them firsthand, and photographing or drawing them (no collecting please). See Recommended Hikes for maps to the search areas I’ve mentioned for each of the species highlighted below. Many milkweed species are now readily available for purchase at gardening stores or online. If you would like to help to save Monarchs and other pollinators by planting milkweed species in your yard, or at your school, park or business, be sure to purchase species suited to your growing conditions, that are not hybrids,* and that are native to the area where you plan to plant them, ideally within fifty miles. By choosing plants that have co-evolved with pollinators and other insects native to this area, you can be sure you are supporting their life cycles with needed resources. *In hybrids (and “cultivars”), instead of the simple nectar guides like those of native plants, that can be accessed with a butterfly’s long tongue, “. . . a bloom can be changed enough in scent or shape that butterflies can’t recognize them or access the nectar.” This is just one example of why using native plants is so important. From www.prairienursery.com.

Scientific Name: Asclepias incarnata General Characteristics & Habitat: typically grows to 3 to 5 feet tall; has deep underground stems; spreads via rhizomes; prefers wet soils (marshes, bogs, ditches). In proper locations, self-seeds prolifically. Flowers: multiple somewhat flat-topped clusters of flowers at tops of stems and branches; flower petals tend to be pale rose to rose-purple, with whitish hoods. Bloom time: mid-June to early September Stem, Leaves, Pods: stems are smooth and branched at the top; leaves are opposite, narrow (about 1 inch wide), oblong or lance-shaped, narrow at the base, and have short stalks. Pods are slender and papery, wrinkled, usually in pairs, terminal on stem. Finding them to view: along ditches and creeks and other sunny wet areas. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Meiners Wetlands and Clear Creek Knolls.  See the sketchbook page above for details on habitat, flowers, stems, leaves and pods. How to find them to view? Look in mostly sunny, undisturbed areas, along railroad right-of-ways, typically in drier soils. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Clear Creek Knolls and Thelma Carpenter Prairie. If you like a challenge, here are several milkweed species that are much more rare than the above species, that you may be able to locate for viewing and/or decide to purchase to grow yourself. Each is unique, even among milkweed species, in their own way.  The sketchbook page shows details on habitat, flowers, stems, leaves and pods. Where to find the poke milkweed to view? Look in dappled woods or other semi-shaded areas, in rich, moist soil. Don’t give up if you see them one year and not the next — they are known to disappear for years at a time and then reappear in abundance. At Nachusa Grasslands, areas outside the bison enclosures to look include Stone Barn Savanna and Big Jump. Currently at Nachusa Grasslands, both Sand (above) and Tall Green (below) milkweeds are only known to be within the bison units. Take this as a challenge to find them elsewhere! Sand milkweed is about 2 feet tall, with the flower cluster well above its leaves, in dry, sandy soil where there is sparse vegetation. Tall Green is easy to identify (see below), and seems to like partial shade and soil with good drainage. Wishing you some happy milkweed exploring! All photos and video were taken by Betty Higby at Nachusa Grasslands, except the Short Green Milkweed pod, which was taken at Midewin. Text and sketches by Betty Higby, who is a volunteer at Nachusa.

2 Comments

James McGee

5/6/2017 08:48:39 pm

One of my favorite milkweeds is not discussed in your post. I have always been a big admirer of Asclepias lanuginosa (Wooly Milkweed).

Reply

Betty Higby

5/7/2017 03:56:42 pm

Our Nachusa Grasslands plant list includes Asclepias lanuginosa, which means that it was at one time confirmed to be here. However, I have not found anyone who has seen it here in the past few years. I am still hopeful and still looking. I did not want to include any species that has not been identified here recently. I agree, though, great plant!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed