|

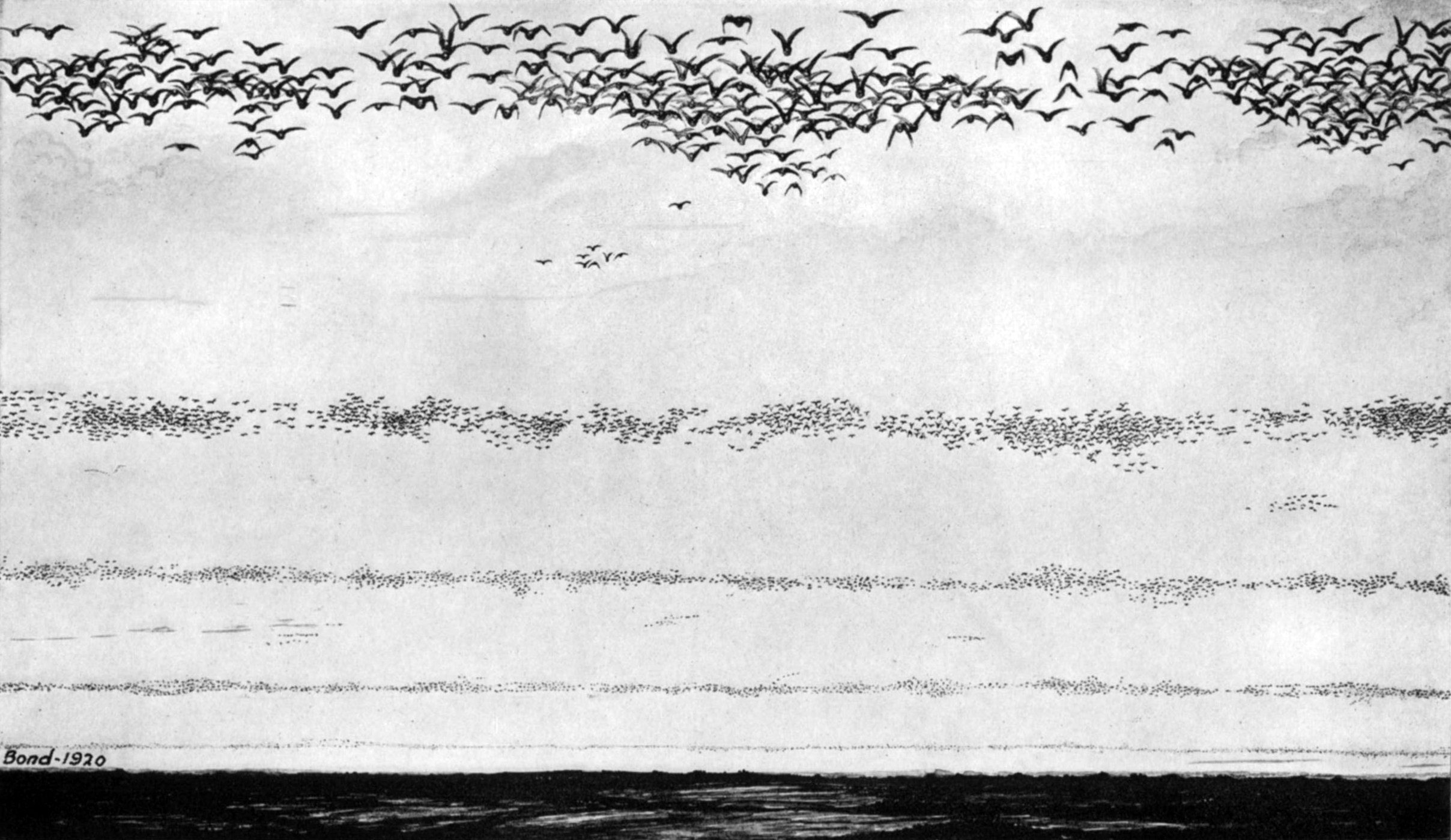

There was a time when seasonal migrations of passenger pigeons arrived with “a loud rushing roar, succeeded by instant blackness.” A black dense cloud of birds would darken the sky for hours, if not days, over the place we now call Nachusa. Passenger pigeon droppings fertilized the earth. The birds’ consumption of woodland seeds was an important mode of dispersal for many plants. While roosting and nesting the combined weight of their bodies was enough to break branches and topple whole trees, resulting in a thinning of the forest which allowed light to reach the ground. A flock of the now extinct birds visited Oregon, Illinois in 1843. Observer Margaret Fuller remarked, “Every afternoon [the pigeons] came sweeping across the lawn, positively in clouds, and with a swiftness and softness of winged motion, more beautiful than anything of the kind I ever knew. Had I been a musician, such as Mendelssohn, I felt that I could have improvised a music quite peculiar, from the sound they made, which should have indicated all the beauty over which their wings bore them.” It is hard to overemphasize just how numerous passenger pigeons were. The dramatic drop from the flocks of billions to zero in less then a human lifetime was a wake up call to the exploitation of birds and other wild animals. The disappearance of the passenger pigeon prompted legislators to enact laws protecting birds and game. Representative John Fletcher Lacey, on the floor of the House of Representatives on April 30, 1900, introduced what would become the first Federal bird-protection law.

Nachusa is the home of many plants, animals, birds and insects that were once common and are now rare. Walk one of the five trails at Nachusa and bear witness to rare species in revival. A few examples of rare species that call Nachusa home: I recently had the pleasure of experiencing a rare bird at Nachusa. I was at the Headquarters Barn after a day of adventure and when I heard the call I wondered, “What bird makes this wonderful sound?” It announced its name with each call: “Whip-poor-will, Whip-poor-will.” Once a common bird, whip-poor-wills, like all nightjars, are in steep decline. According to The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s “All About Birds,” night jars are hard to breed in captivity, and there are no excess populations from which to take birds for a reintroduction project. Scientists are not sure of the reasons whip-poor-wills are disappearing. Loss of open under-story forest is one possibility. At Nachusa clearing brush and returning fire to the woodlands begins to restore habitat. This habitat provides an abundance of insects, including moths, beetles, stone flies, and grasshoppers. These are favorite foods of whip-poor-wills; they hunt just after dusk and right before dawn, or on moon-bright nights they may hunt all night long. In one of those true mysteries of nature, whip-poor-wills seem to time egg laying so the chicks hatch ten days before a full moon, providing the parents extra time to gather food for fast growing chicks. When at Nachusa listen for the sounds of this rare bird. The passenger pigeon migrated into history before people realized the toll their activities were taking on wildlife. As awareness grew, people acted through government to protect native birds and animals. In time non-profit organizations such as The Nature Conservancy (TNC) bought lands of high biological diversity to preserve as many species as possible. TNC’s Nachusa Grasslands preserves and restores high-quality grassland, savanna, and woodland remnants for the future. Those high-quality remnants are the anchor areas to restore former agricultural areas back to nature. The Friends of Nachusa Grasslands aids this effort by supporting science research, to better understand the impacts of restoration efforts and how they might be improved. It’s too late for the passenger pigeon, but not the whip-poor-will and other species that will benefit for generations to come from the efforts at Nachusa. This week's blog was written by Paul Swanson, a volunteer at Nachusa. Sources

Prince, Jennifer. Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America. New York: Basic Books, 1999. "Passenger Pigeons in Your State, Province or Territory." (2012). Retrieved from: http://passengerpigeon.org/states/Illinois.html. Greenberg, Joel. A Feathered River Across The Sky. New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2014. "Eastern Whip-poor-will." (2017) Retrieved from: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Eastern_Whip-poor-will/overview.

2 Comments

Bernie Buchholz

3/16/2018 03:03:20 pm

Paul. Thanks for connecting whip-or-wills status with passenger pigeons. Bennett Woods was burned today. Good habitat for w-o-w?

Reply

Paul Swanson

4/11/2018 10:40:13 am

Thanks Bernie, this gives an opportunity for one more quote about passenger pigeons. From James S. Buck 1837. "Vast numbers of pigeons all spring and summer of 1837. The ground cleared by fire was covered with pigeons in search of acorns"

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Blog CoordinatorDee Hudson

I am a nature photographer, a freelance graphic designer, and steward at Nachusa's Thelma Carpenter Prairie. I have taken photos for Nachusa since 2012. EditorJames Higby

I have been a high school French teacher, registered piano technician, and librarian. In retirement I am a volunteer historian at Lee County Historical and Genealogical Society. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

CONNECT WITH US |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed